An impressive Iron Age II fortress and settlement, built on the summit of a steep ridge overlooking the Jordan valley near Nahal Tabor stream.

Home > Sites > Jordan Valley > Horvat Ziwan (Kh. ez-Zawiyan)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial Views

* Access

* West Side

* North side

* South side

* East side

* Summit

* Lower east

* Ceramics

* Stone Tools

* Video

* Experts visit

Etymology

Links

Background:

On Horvat Ziwan (Khirbet ez-Zawiyan) are ruins of an impressive Iron age II fortress and settlement, built on the summit of a steep ridge. Rising over 100m above highway #90, it commands the views of the Jordan valley south of the estuary of the Nahal Tabor stream.

Location:

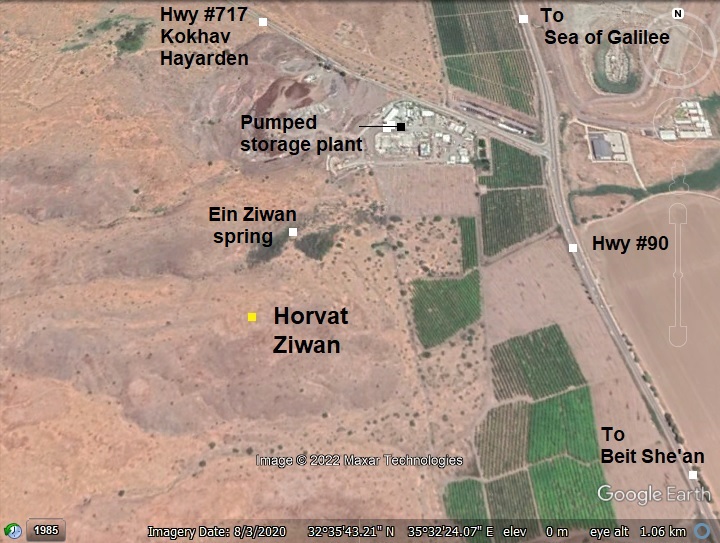

The ruins of Horvat Ziwan are located on a ridge, south of the valley of Ein Ziwan spring. The site is at an altitude of 109m under sea level, 100m above the highway below. It is 1.5km east of Kokhav Hayarden – Kaukab el Hawa (Belvoir) Crusader fortress.

History:

-

Biblical times (Iron Age II)

Majority of the ceramics recently collected on the site were dated to Iron Age IIa-b – 10th-8th century BC – the period of the Northern Israelite Kingdom. The city was was probably abandoned following the Aram-Damascus or Assyrian conquests, and since then it was left untouched.

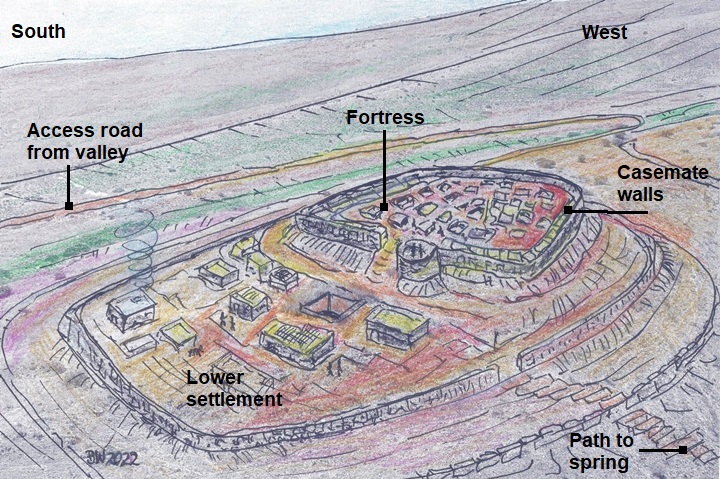

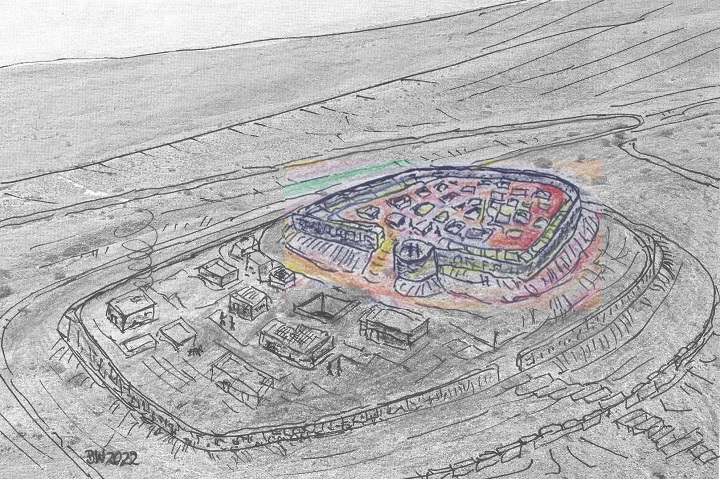

The ancient city was protected by 2-3 peripheral walls, with a small settlement on the lower east side of the fortress. A raised area, on which the fortress was built, has a elongated shape, covering an area of ~6 dunams. It rises east to west, measuring 80m long by 70m wide. Inside the fortress are two dozen small structures built of basalt stones, some of them probably grain silos. The inner (upper) wall around the raised fortified area is a casemate type – parallel walls with a space between and with internal chambers. Possible remains of a tower are visible on its north eastern foothill. The access road was probably along the southern foothills.

A figurative illustration is shown here, viewing the site from the north east side. It is based on initial findings, and will be updated after an excavation is conducted and provides accurate details.

Figurative illustration of Horvat Ziwan during the Biblical times

The Biblical city is identified by some scholars as Beth Pazzez (בֵית פַּצֵּץ), a site that appears in the list of Issachar cities (Joshua 19:17,21):

“…for the children of Issachar according to their families….and Remeth, and Engannim, and Enhaddah, and Bethpazzez”.

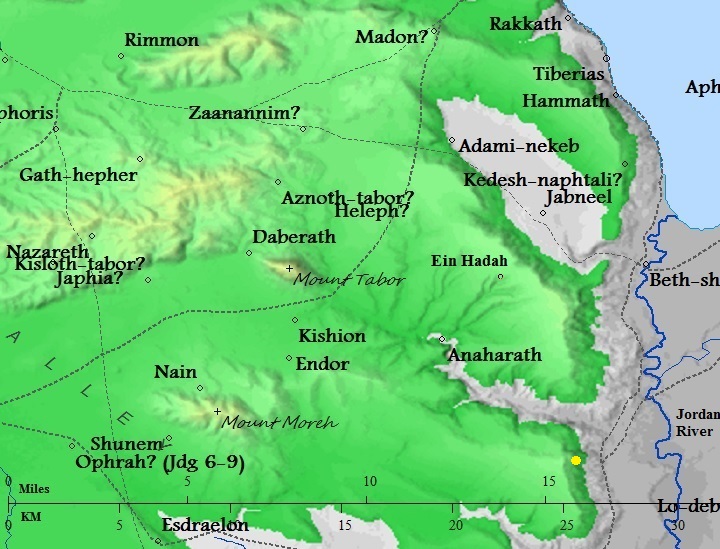

Cities and roads during the Canaanite and Israelite periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below. Horvat Ziwan is marked with a yellow circle, 1.5km south of Nahal Tabor. Biblical Anaharath, is identified at Tel Rekhesh upstream on Nahal Tabor.

Map of the area around the site – from Canaanite/ Israelite to Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

The location of Horvat Ziwan was strategically important during the ages, overlooking several major routes:

- A major North-South highway along the Jordan valley passed below the site. David Dorsey (“The roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”, 2018) marked it as Bronze/Iron age ‘A3’.

- ‘T4’ road from Mt. Tabor thru Tel Rekhesh to ‘A3’.

- Another major route, ‘T5’, a Bronze/Iron age road T5 from Afula via Kh. El Hadad (near Taibe), on the steep descent thru Ein HaYadid, Khirbet Ziwan and Horvat Zavon (850m south) to the Jordan River ford crossing at Tel Kittan. (see the Tabor Delta river crossing page)

- Towards east, a river crossing was located 3km from the site, passing thru a ford on the Jordan river near Tel Kittan.

- Northern Kingdom of Israel

According to initial assessment, the major period of the site was during the IIa-IIb (1000-700BC). The following list, based on the Bible, names the Kings of the Northern kingdom of Israel during these times. We assume that the great construction was conducted in the times of the House of Omri, and the destruction/abandoned period was during the Assyrian conquests. However, this will be determined following the excavation of the site.

Starting from the split of the Unified Kingdom, the kings of the Northern Kingdom of Israel and their reigning years were:

- Jeroboam I (931-910 BC) – the Founder

- Nadab (910-909 BC)

- Baasha (909-886 BC)

- Elah (886-885 BC)

- Zimri (885 BC)

- Omri (885-874 BC) – House of Omri

- Ahab (874-853 BC)

- Ahaziah (853-852 BC)

- Joram (852-841 BC)

- Jehu (841-814 BC) – House of Jehu

- Jehoahaz (814-798 BC)

- Jehoash (798-782 BC)

- Jeroboam II (782-753 BC) – period of prosperity and expansion.

- Zechariah (753 BC

- Shallum (752 BC)

- Menahem (752-742 BC)

- Pekahiah (742-740 BC)

- Pekah (740-732 BC) – 1st Assyrian conquest

- Hoshea (732-722 BC) – 2nd Assyrian conquest, end of the Kingdom

It’s important to note that the chronology and lengths of reign for some of these kings are subject to debate and may vary depending on the historical sources consulted.

- King Jeroboam II

Jeroboam II was the 14th king of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, who reigned from 782-753 BC. He was the son of King Jehoash and his mother’s name was Zibiah. Under Jeroboam II’s reign, the Northern Kingdom of Israel experienced a period of prosperity and expansion. He restored Israel’s borders to their extent during the reign of King Solomon and even expanded them further, conquering territories in Syria and Transjordan. He also enjoyed a time of peace and prosperity within the kingdom, with trade and agriculture flourishing.

However, despite his many successes, Jeroboam II’s reign was not without its problems. The book of Amos in the Hebrew Bible describes how social inequality and injustice were rampant during his reign, with the wealthy and powerful exploiting the poor and vulnerable. This eventually led to God’s judgement on the Northern Kingdom and its downfall ~30 years after his reign.

Overall, Jeroboam II is remembered as a successful king who oversaw a time of prosperity and expansion for the Northern Kingdom of Israel. It is probable that during his times it was when the site at Horvat Zivan was at its peak.

- Assyrian intrusions and destruction (732-712 BC)

In 732 BC was an intrusion to the North of Israel by the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III, who annexed the area (as per 2 Kings 15: 29): “In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took … Galilee…and carried them captive to Assyria”. This intrusion affected the north of the Kingdom.

Assyrian forces attacking – AI generated by Bing

Following the death of Tiglath-Pileser, the Egyptians encouraged the people in the occupied territories of the Assyrians to revolt. Hoshea, King of Northern Israel, joined this mutiny, but made a fatal mistake. This time the Assyrians crushed the remaining territories of the Northern Kingdom. The intrusions of Shalmaneser V and Sargon II in 724-712 ended the Northern Kingdom (2 Kings 17: 5-6):

“Then the king of Assyria came up throughout all the land, and went up to Samaria, and besieged it three years. In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes”.

The villages in the Galilee and Samaria were destroyed or abandoned, including this site. It was never built again and remained intact until these days.

- Crusaders period

A large Crusaders fortress, Belvoir, was constructed 1.5km west of Horvat Ziwan, on the high mountain (400m above the height of Ziwan). The Crusaders valued the location of this place, probably for the same reasons that the Iron Age builders of the fortified Horvat Ziwan had: the proximity to major roads and to river crossing points, and the heights that provided both a natural protection and great visibility of the area around it.

-

Ottoman period

An Ottoman railway passed in parallel to highway #90, 1km away from the site, on the way to cross the river 3km North East of the site. See remains of this railway near Tel Yissachar.

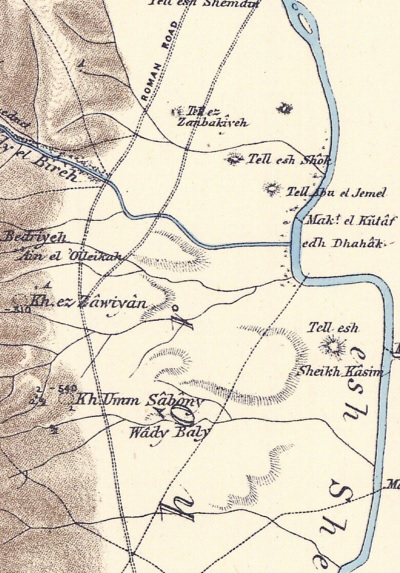

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their map is shown below. The site, Kh. ez Zawiyan, appears near a split of two Roman roads passing at its foothills: one leading north to Tiberias, the other east to a river crossing above a bridge (Jisr el Mujamia – modern Gesher). The survey team merely wrote about the site: (SWP Vol 2, p. 125): “Foundations of buildings, apparently modern”. Another ancient site is close by south of the site – Kh. Umm Sabony (Horvat Savon) – another Bronze/Iron age town.

Nahal Tabor stream is “Wady el Bireh” north of the site, and it flows into the Jordan river on the right.

Jordan River crossings were mostly based on crossing fords. They appear on the map as Mak.t – short for Makhadet – Arabic for ‘ford’. Two fords are marked here:

- a river crossing at Mak.t el Kitaf edh Dhahak (near Tell abu el Jemel – Tel Shushan).

- a river crossing at Mak.t esh Shekh Kasim – near Tell esh Sheikh Kasim (Horvat Zer).

Part of Map sheet 9 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

- British Mandate

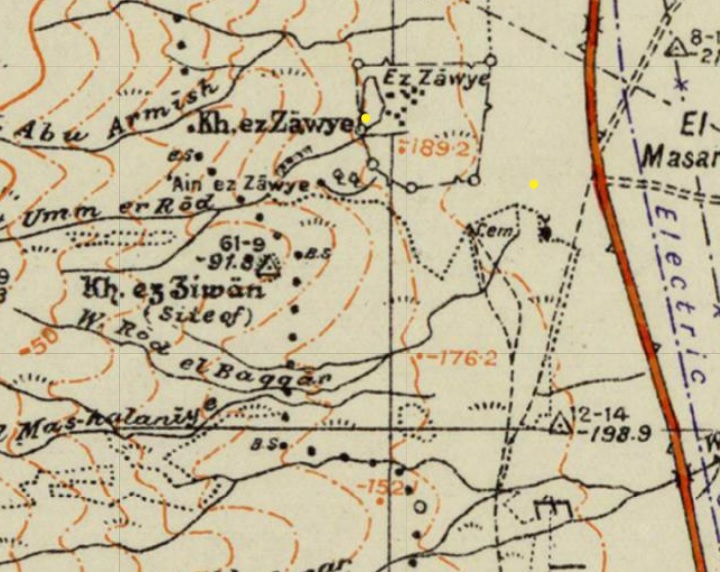

A 1940s British map shows the area around the site with more details. The site is marked here as Kh. ez Ziwan. It overlooked the Beit Shean-Tiberias road which passes in the fields east of the site. A spring (‘Ain ez Zawye) is located in the valley north of the site. Another ruin was located north east of the stream, named Kh. ez Zawye.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

-

Modern Times

A Kibbutz, Neve Ur, was established in 1948 in the valley, 1km south east of Horvat Ziwan. It was named after Ur Chaldees – named after Abraham’s city before leaving to Canaan (Genesis 11:31): “…and they went forth with them from Ur of the Chaldees, to go into the land of Canaan…”.

A new project, based on pumped storage hydropower method, is being built north of the site, using the 400m height difference between the heights and the valley to generate electrical power. Water is raised from a lower to an upper reservoir, and released down to generate electrical power.

Horvat Ziwan is today a secluded ruin that is seldom visited. BibleWalks is working with leading archaeologists to open a trial excavation on this exciting site.

Photos:

(a) Aerial Views

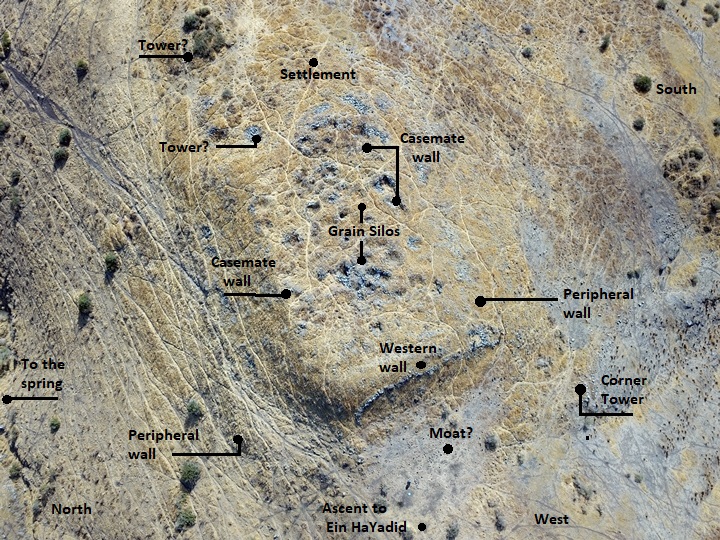

A drone capture this view of the site, with a view towards the east. The site was protected by 3 peripheral walls, with a raised fortress in the center, and a small settlement on the lower east side of the fortress.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The fortress has steep foothills on 3 sides. On its weaker west side the builders of the fortress strengthened the defense by raising a higher wall and cutting a moat into the natural slope of the ridge. Remains of the base of the wall is seen along the western edge. Behind it was a casemate wall, typical of Iron Age II fortifications.

In the background, below the site, is highway #90 (Beit She’an to Tiberias). This was also the route of the ancient south-north trade roads.

Inside the fortress are two dozen small structures built of basalt stones, including grain silos. The inner (upper) wall around the raised fortified area is a casemate type – parallel walls with a space between and with internal chambers.

The following illustrated photo shows another top view, with direction east on the upper side. The points of interest are shown here, and are detailed in the remainder of this web page.

According to our survey, the site was not in use since it was abandoned, with some walls still standing up to 1m high. This is a unique preservation of an ancient Iron Age site.

(b) Access to the site

We first ascended by foot from the valley of the Ein Ziwan spring, on the north side of Horvat Ziwan. The spring was flowing during the summer, keeping the trees alive. The ascent up to the site was difficult due to the steep climb and the summer heat (40 degrees Celsius).

A better approach to the site was found on the next visit to the site, driving halfway up along a dirt road on the south side (seen here). This seems like the original route of the access road to the site, although it did not reach all the way up.

We then continued climbing by foot up the steep southern slopes.

A view of a lower peripheral wall and the western side of the fortress is in the following photo.

On the south west side of the middle peripheral wall are probable remains of a corner tower, seen in the photo below with a view towards the south. The Iron Age access road may have used this side for the ascent and entry gate.

A view of the lower terrace, looking to the west, is in the next photo.

High above in the far background, 1.5km west and 300m higher, is the top of the mountain where the Crusader fortress (Belvoir), Meir Har-zion’s farm (“Ahuzat Shoshana”), and Ein HaYadid (Bronze/Iron Age site) are located.

(c) Western side

The drone captured this view from the north west side. The builders of the fortress cut into the natural slope of the ridge creating a moat and building a higher wall.

A closer view of the western wall is next.

Behind the wall is a second line of a wall – creating a casemate type wall.

A section of the visible casemate wall, above the western side, is seen below.

All the walls in the site are made of roughly cut basalt fieldstones. The basalt stones served as base of a sun-dried mud brick wall that increased its height, but now has crumbled and fallen.

Note that the archaeological measuring stick, seen on the bottom right side, has 10cm black and white bars.

Another view of the casemate wall, with archaeologist Ayelet Goldberg-Keidar who conducted this survey:

(d) North side

The north side of the fortress overlooks the valley of Ein Ziwan spring. The spring probably provided water to the fortress. Today its waters feed a small ‘jungle’ along the valley.

Behind the valley is the pumped storage hydropower station, which is currently (2022) built to harness the height difference between the mountain and the valley to create electricity.

Although this side is naturally protected by the steep foothill, a casemate wall was built along the north side. This photo shows several chambers that were built along the wall.

(e) South side

The south side is also protected by a casemate wall. This photo is a view towards the east.

The Jordan river, seen in the background, passes from left (north) to right (south). The river crossing points were on the north and south of the estuary of Nahal Tabor stream.

Another view of the southern wall, looking west:

(f) Eastern side

The eastern wall of the fortress has also a line of casemate wall. This view is towards the south.

(g) Summit

The fortress is built on a raised area, with an elongated shape, measuring 80m long (east-west) by 70m wide (north-south). It is protected by a casemate wall from all sides.

The surface of the raised area is dotted by a large number of enclosed chambers.

With the weed covering the structures, it is hard to asses the detailed plan of the ruin.

Nevertheless, measurements were made to provide a preliminary plan of the ruin.

The walls of these structures are made of rough basalt rocks.

Some of the walls of the structures were preserved to a meter or more high.

What was the purpose of these chambers? Perhaps, some were used for accommodation. Others grain silos and water cisterns. They may have also be used for storing goods. Only a detailed archaeological dig could provide answers. Ceramics inside the chambers/silos were dated to the Iron Age period.

(h) Lower Eastern side

On the east side of the raised fortress was another stepped platform, as seen on this aerial view.

This platform seems to have been an area where a small settlement was built. Traces of ruins and an abundant number of ceramics indicate this possibility. Perhaps, the settlement covered other areas around the fortress. A ceramic survey of the area around the site could provide more clues.

In the photo below is a view of this area under the fortress. Ayelet is seen here sitting near a bush that may have grown over a cistern or underground cavity.

Closer to the walls of the fortress is a pile of stones. It may have been a tower.

(i) Ceramics study

While it was hard to find any ceramics on the top of the fortress, the lower east side revealed plenty of ceramic fragments that assisted in dating the site. These were found in porcupine holes, especially on the south east foothill. The mammals dig into the ground, pulling out dirt and pottery fragments, making it easy to sift thru the soil and pick up the ceramics.

After a quick survey of the porcupine excavated areas, we grouped the ceramics in the photo below. They were all dated to Iron Age IIa (1000-925BC) and IIb (925BC-700BC) – the period of the Northern Israelite Kingdom. Few sherds were dated to the Early Bronze and Chalcolithic periods.

Note that all ceramics were left on the site.

The following photos focus on several pottery samples:

8: Loom weight?

This piece has a hole pierced through. It may have been a loom weight, used as part of the weaving textile process. Such weights were used to hold in tension the vertical threads in a vertical standing loom. This technology started in the Early Bronze period, while during the Iron age it was used in a large scale textile production [link].

9: Handle Cooking Pot with Potter’s Mark (compare to a similar piece from Maresha)

10. Iron age II handle, potter’s marks

11. In addition to the ceramics found in the eastern foothill, a review of the silos revealed pottery sherds, probably most of them dated to the Iron Age IIa-IIb.

(j) Stone tools

In addition to Ceramics, tools made of other materials were found during our short survey of the site.

- Quartz rubbing stone – Quartz rubbing stones from the Iron Age were multifunctional tools, commonly found in archaeological contexts across the Levant. Quartz rubbing stones are often found alongside grinding tools, in domestic spaces, or near storage areas, suggesting their role in everyday tasks like food preparation. The stones were also used in tool maintenance, textile and leather production, and for smoothing surfaces for construction and pottery.

2. Basalt grinding base stone – used to grind grains for flour. Along the right side are a series of small holes that their function is not understood to us.

Note that similar items were unearthed in the Iron Age II layer in Megiddo.

The other side of this basalt grinding base stone:

Another basalt grinding stone:

(k) Aerial Video

![]() Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Video and photos captured on Sep 2022

A field survey video was also published, following our return visit survey to the site on Jan 3, 2025.

(k) Experts Visit

On April 2, 2023, we were honored by a visit to Horvat Ziwan by the distinguished archaeologists Professor Emeritus Amihai Mazar and Doctor Achia Kohn-Tavor of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Prof. Mazar is one of the most senior experts on Biblical Archaeology, and among his major projects are the Beth Shean Valley Archaeological Project and the excavation and publications of Tel Beit Shean and Tel Rechov. Doctor Kohn-Tavor is currently leading excavations in Israel and has published a report on the area of central Jordan valley.

From left: Dr. Kohn-Tavor, Ayelet Goldberg-Keidar, Prof. Mazar

The experts reviewed the ruins and analyzed the ceramics and agreed that the major period of the site is Iron Age IIa-IIb. They expressed great appreciation of the state of preservation of the site, and recommended to excavate the site.

We are looking forward for a trial excavation to further explore the site.

Prof. Mazar and Dr. Kohn-Tavor, with BibleWalks members Yoram and Roni Hofman

Etymology (behind the name):

- Tel (Tell) – mound (See more on the story of a Tel).

- Makhadet – Arabic: Ford

- Khirbet Zaiwiyan – Arabic: ruin of tares (darnel – a type of weed) – [PEF names dictionary, p.163]

- Horvat Ziwan – Modern name, based on the Arabic name

Links:

* External, archaeological links:

- Crossing the Jordan river during the Biblical period – north versus south – David Moster, Aram 29 (2017), pdf

- Late Bronze Survey in Jordan valley – James Mark Schaaf (545 pages, 2012, thesis, Univ S. Africa); great resource!

- Bergman & Brandsteter Arch. surveys in Beit She’an valley (1940-1941:86-90, Hebrew)

* External, other links:

- https://survey.antiquities.org.il/index_Eng.html#/MapSurvey/2136/site/21302

- Pumped storage Kokhav Hayarden – Power station north of the site

- Prof. Amichai Mazar – The Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

* Internal links:

-

Horvat Zavon and Sheti (Youtube) – nearby sites

- Tel Ein HaYadid – nearby site

- Horvat Ziwan on Jordan Valley sites map

- Tabor Delta river crossing – nearby sites

BibleWalks.com – exploring the ancient sites of Israel

Tell Abu Sus/Sakut<<<—previous site—<<< All Sites>>> — Next site—>>> Nahal Tabor delta

This page was last updated on Feb 27, 2025 (add potter’s mark handle)

Sponsored links: