Iron Age and Byzantine Sites on the side of a major trade route in the esh-Shakk valley.

Home > Sites > Samaria > Esh-Shakk valley sites

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Valley

* Spring

* Kh. Esh Shakk

* Muntar Esh Shukk

* Umm Ghazal

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Khirbet esh-Shakk is a large Byzantine period village located on a ridge above Wadi esh-Shakk, in the north eastern Samaria hills. It overlooked a major road that connected Shechem and Samaria to the Jordan valley and Transjordan hills. To the east of the valley are 2 small Iron Age forts – Muntar esh-Shukk on the top of the hill on the east side, and Kh. Umm Ghazal on the lower ridge above the valley.

Map / Aerial View:

An aerial map is shown here, indicating the major points of interest around the site (in yellow squares). The ancient route made a direct pass along the esh Shakk valley, rather than taking a longer way along the Wadi Malha valley where the modern road #578 is located.

History:

Overview

In the area around the valley of esh-Shakk are sites of various periods. They were constructed at this point to protect and support the ancient trade route between Samaria and the Jordan Valley. The sites include:

- Muntar esh-Shukk – Iron 1 II-III period (1150-1000BC)

- Kh. Umm Ghazal (also: Khirbet esh-Shakk) – Iron II (majority; 1000-586 BC) and Iron III periods (586-332 BC)

- Khirbet esh-Shakk – A Byzantine period village (324-624 AD)

In the close vicinity are additional historic sites – a total of 8. This implies the importance of this mountain pass.

- Iron Age I

The earliest fortress – Muntar esh-Shukk (also Muntar esh-Shakk) was built on top of the summit during the 11th century BC (Iron Age I b-c). It dominated the entire area and the trade road along the Esh-Shakk valley. This small fortress consisted of a casemate wall protecting a central structure or tower.

- Iron Age II

The lower Iron Age II site – Kh. Umm Ghazal (also: Khirbet esh-Shakk) – may have been as part of a royal large scale project to improve the protection of the major road systems from the east into the Kingdom. Three such fortresses are considered to be part of these project: Muntar esh-Shukk, el Makhruq at the entrance to Nahal Tirzah, and Rujm Abu-Mukheir on the road ascending from Fazael brook.

These road side fortresses can be dated to King Solomons reign (965-928 BC), as per the Bible’s account of the King’s metal works (1 Kings 7:46)” “In the plain of Jordan did the king cast them, in the clay ground between Succoth and Zarthan”. In his article on the 3 fortresses, Adam Zartal also suggested other Kings who may have been responsible for these fortifications (Jeroboam, Ahab). Jeroboam I, the first King in the Northern Kingdom (reigned 928-907 BC), relocated his capitol city from Shechem to Penuel on the east side of the Jordan river, and so these fortresses protected the roads inter connecting his Kingdom (1 Kings 12:25): “Then Jeroboam built Shechem in mount Ephraim, and dwelt therein; and went out from thence, and built Penuel.”.

- Biblical map

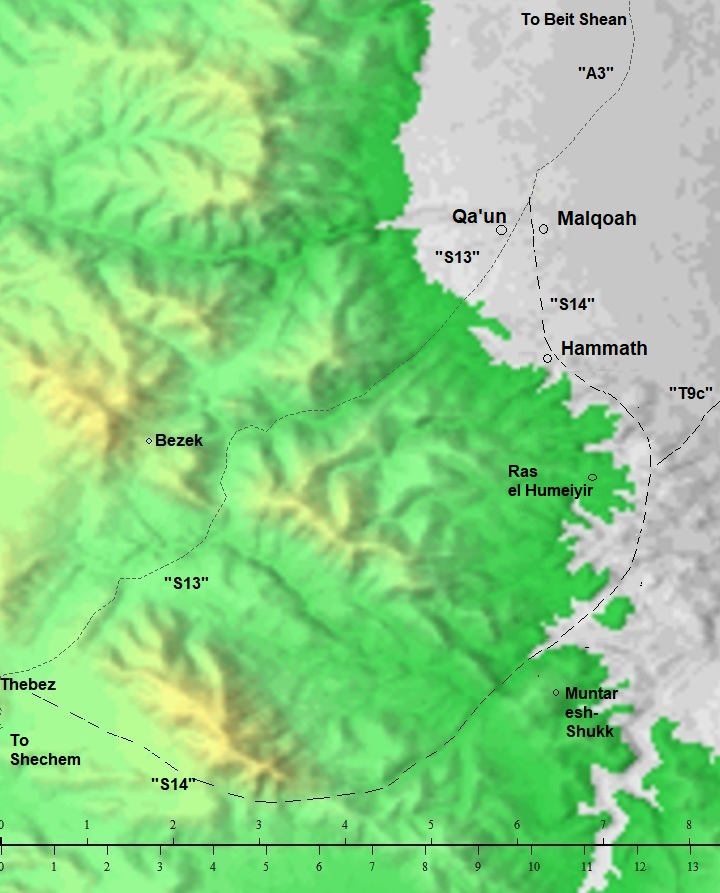

The cities and roads during the Canaanite and Israelite periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below. The map shows the 2 routes from from Samaria to Tel Rechov (Rehob) and Beit Shean (most important sites in this region) and to TransJordan Mountains via the fords along the Jordan river near Tell es-Sakut.

Another ancient road to Jericho and to Samaria passed on the side of the site, but is not shown here.

Map of the area around Muntar esh-Shukk- during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

David Dorsey (“The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”, 2018) shows a detailed map of the roads around the site during the Bronze/Iron age. The main road from Rechov/Rehob southwards is marked as A3. It passes Tel Malqoah, 3km north of Hammath, where the road splits to two routes towards Shechem and Samaria:

- route S13 – The northern route, via Wadi el Khashneh, to Aser (modern Tayasir) and Thebez (Tubas). A Roman road also used this route, as indicated by milestones found along the route.

- route S14 – The southern route: After passing Hammath, it continued south along the foothills to Ras el-Humeiyier. It then turned south west thru the valley of esh-Shukk, where a pair of Iron Age fortresses guarded the road, and continued west along Wadi Malikh to join route S13 at Aser (Tayasir) and Thebez (Tubas).

Edward Robinson, the “father” of Biblical Geography, was told that there were 2 routes to cross from Samaria to the Jordan river (E. Robinson, published 1857, “Biblical researches in Palestine, and in the adjacent regions”, p. 307):

“We had learned, that there were two roads by which we could reach the Ghor ; one direct through Wady Khushneh, and so to Beisan [BW: S13]; the other, following down Wady Malik by the castle [BW: Burj el Maleh] and salt springs, led also to Sakut (Succoth) , but was circuitous [BW: S14]. We chose the latter…”.

Another route (“T9c“) from Hammath and Ras el-Humeiyier turned east towards the crossing point on the Jordan river at Tell Abu es-Sus, via Kh. ein Sakut (Biblical Sukkot?) which guarded the river crossing point at the fords.

- Byzantine period

During the Byzantine period a large (15 dunams) village was built on the north side of the valley – Khirbet Esh-Shakk. The village provided services for the travelers, and built installations in the valley – dams, farming fields, winepress, aqueduct and well.

In the Byzantine period other new villages were established along the road, such as the village south of Tel Hammath – 3KM to the north.

- Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

Edward Robinson, the “father” of Biblical Geography, visited the site on his travels in 1852 (E. Robinson, published 1857, “Biblical researches in Palestine, and in the adjacent regions”, p. 309):

“Setting off again after five minutes, we left Wady Maiih, and struck upon a course about N. E. over the low ridge. Entering immediately the head of a shallow Wady, called eshShukk, we followed it down on the same course, till we came at 9.15 to a spring of pure though warm water ; with the , ruin of a village on the left bank, also called esh-Shukk. Here we stopped for ten minutes. Proceeding down the valley, our course soon became E. by N. and the Ghor began gradually to open before us ; so that at 9.40 we stopped for five minutes for observation and bearings.’ About 9.55 Wady Malih again came in from the southwest under a low ridge like a windrow, after a long circuit among the hills. It here had a small stream of water, which seemed to flow on quite to the Jordan. The Wady eshShukk is of course one of its tributaries”.

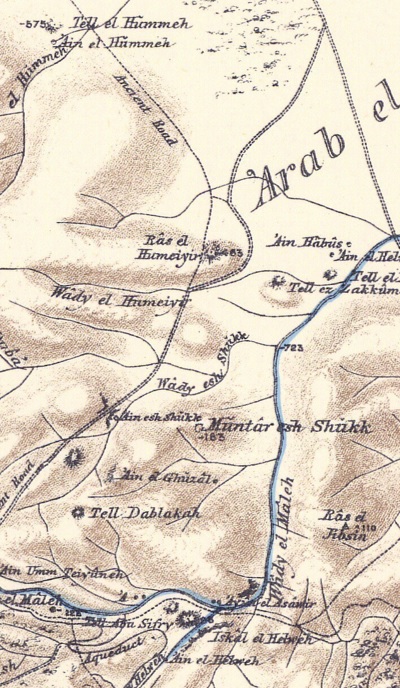

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. This map is part of sheets 12 of their survey results. The site (“Muntar esh Shukk”) is located near the spring of ‘Ain esh Shukk, along the route of an ancient road (the double dashed line), connecting Samaria to the Jordan valley. This route traverses the valley parallel to the Wadi el Maleh where the modern road is now located.

Part of map sheet 12 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Their report of the site on the hill is merely a short description(Volume 2, Sheet 12, pp. 243):

“Muntar esh Shukk – Traces of ruins on a high hillock”.

They described the ancient road (Volume 2, Sheet 12, p. 232):

“The southern branch runs east from Teiasir (where there is a Roman milestone) down Wady Maleh, and is marked in places by side walls. At ‘Ain Maleh it gradually turns north-east, and joins the Jordan valley road east of Tell el Hummeh, running at a higher level as far as the Ras el Humeiyir, where it gradually descends”.

- British Mandate

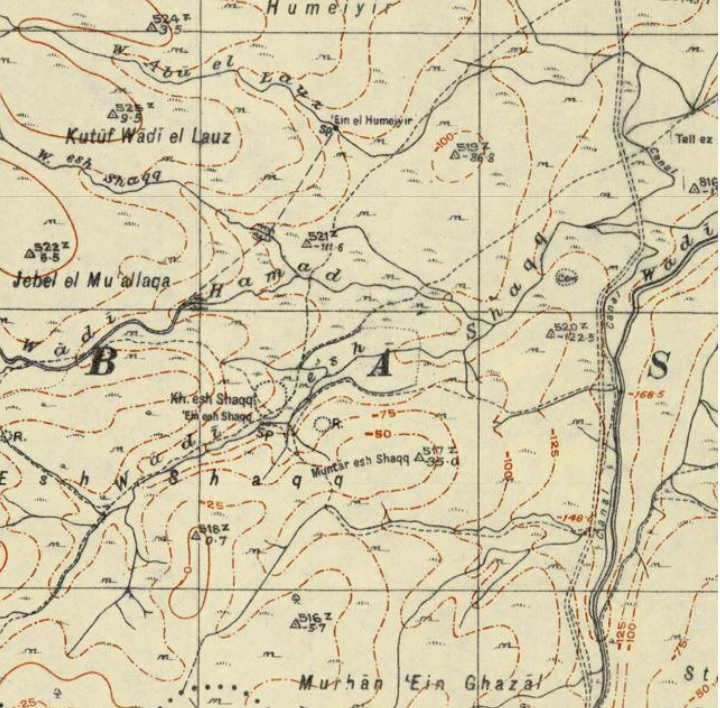

A 1940s British map shows the area around the sites with more details. The 3 sites around the spring of Ein esh Shaqq are: Kh. esh Shaqq, Muntar esh Shaqq, and “R.” between them. The ancient route passed along the south side of Kh. esh Shaqq, just above the valley, and passing near the spring. It is illustrated as a dashed line along a south-west to north-east line. It is shown that the route splits in the valley west of Kh. esh Shaqq to a northern road (‘S14’) and a road that continues to Tell abu es-Sus along the Jordan river (‘T9C’).

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

- Modern period

The sites were surveyed by the Har Menasseh Country survey by Adam Zertal (volume 2, sites 81-82-83, pp. 251-259; 1996).

Photos:

(a) Valley of esh-Shakk

The valley of esh-Shakk descends into the southern edge of the Beit Shean valley, 1km south of Moshav Mehola. The area of the valley is 200 dunams. It was the path of ancient routes during the thousands of years, connecting to the cities in the Beit Shean valley and to the river crossing points along the Jordan river.

In this view towards the north east, at the edge of the valley, is the modern road #578 – the northern edge of the Allon road. It ends at a junction near Moshav Mehola (named after Biblical Abel-Mehola), which is seen here at the end of the road. In the far background is the Jordan valley, with the TransJordan mountains behind it.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

In the view below, looking towards south west, are the sites that are reviewed in this web page: Muntar esh-Shakk, an Iron age fortress, on the top of the hill on the left side, the Byzantine village of Khirbet esh-Shakk on the right side, and another Iron Age fortress in the middle between them.

The valley is wide at its north east end. However, the wide valley soon gets very narrow going south west. It cuts thru a wall of rocks and creates a deep gorge (Ma’ok in Hebrew). The ancient route passed on the north side of the pass.

The deep gorge gave its name to the valley and to the sites built around it. The name, esh-Shaak (also esh-Shuuk) means ‘cleft’ – a split in the rock. Another similar gorge, with a fantastic rock formation, is in the nearby Hamad valley – just 300m north west.

Inside the gorge are two dams in series.

A rock-cut aqueduct runs on the north side of the gorge, leading to the lower dam on its east side.

A closer view of the metal pipes at the edge of the dam:

Above the gorge is a 3.5m x 3m wine press complex cut deep into the rock. A round hole is located in the center of the treading floor, used for secondary crushing. The collecting pool is plastered at the bottom.

(b) Spring of esh-Shakk

Inside the valley, before the gorge, is a perennial spring – Ein esh-Shakk. In this extremely dry area, a desert fringe, water is life.

The water used to fill the dams in order to irrigate the crops in the valley below the pass.

A modern built well is located near the spring, just before the valley turns around into the gorge.

The spring of Ein esh-Shakk was an important station along the ancient route. It is still active, supplying waters to the herds.

During the Byzantine period a village was built above it, servicing the caravans that passed here.

(c) Khirbet esh-Shakk

Khirbet esh-Shakk is a large Byzantine period village located on a ridge above Wadi esh-Shakk, in the north eastern Samaria hills. It overlooked a major road (Tubas-Mehola) that connected Shechem and Samaria to the Jordan valley and Transjordan hills. The road passed thru the village, and its well and inns served the caravans passing thru this dry desert mountains area.

The following view is towards the north. The ruins cover an area of 15 dunams and are scattered on the ridge above the valley.

The next aerial view is towards the east, with the ruins located on the lower side of the photo.

The next aerial view below is towards the north east. A modern dirt road, rising from the valley, caused damages to the site, splitting it to two sections:

- Northern section: On the top side of the ruins is a 70m x 40m complex with a small central courtyard and several surrounding rooms, perhaps an inn. It was built of medium size stones, with two phases of construction. Several residential rooms were located on its north side.

- Southern section: another complex, 10m x 50m, also consisted of several rooms. It was built with larger and better quality stones than the other complex. The walls of this structure are visible in this photo near the large green bush on the left side.

In addition to the water of the spring, there are 4 cisterns inside the village.

Next phot: a view towards the east, with Uncle Ronnie reviewing the ruins. The mountain fortress Muntar esh-Shakk is located on the top of the mountain, while the later constructed Iron Age fortress is on a ridge above the valley.

![]() Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Video and photos captured on June 2022

(d) Muntar esh-Shakk

To the east of the gorge are 2 Iron Age forts – Muntar esh-Shukk on the top of the hill on the east side (seen here), and Kh. Umm Ghazal on the lower ridge between the hill and the valley.

During the Iron Age these fortresses overlooked a major trade route (Dorsey’s “S14”), one of the routes along the “Via-Maris”, from Samaria to Hammath and Rehob, and to the fords crossing the Jordan river.

Muntar esh-Shakk translates from Arabic as “the watch tower of the gorge”. From the summit are great views of the ancient route that passed along the esh-Shakk valley.

Another north-east view towards the Jordan valley:

The hillside around the summit is very steep.

A view of the east side shows the modern road #578 to Samaria, going south along Wadi Maleh. The ecological community of Rotem (established 2001) is located on the hill on its east side.

- The summit

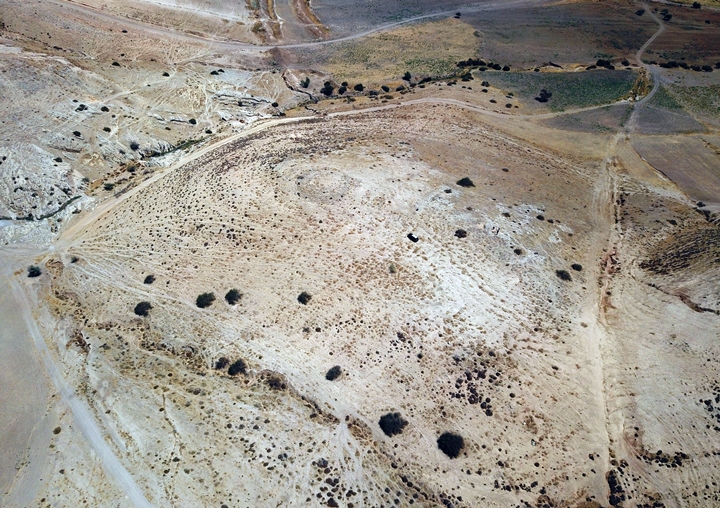

The following drone view is a vertical look towards the center of the summit. A circular pattern is visible around the center, where a peripheral casemate wall was once standing.

On the summit is a pile of rocks in the center. This was a round tower with a 10m diameter.

Several bases of walls can be seen in the center.

A section of a casemate wall was found on the northern hillside, 30m from the center.

On the summit are 3 cisterns that supplied water to the fortress, in addition to the spring from the valley (80m below, 500m away).

- Findings

Archaeologist Ayelet Goldberg-Keidar helped to research the site and identify the pottery scattered on the surface. Here and there were interesting parts we have examined during our brief visit on the hill. All items were returned to their original location.

Ceramics collected on the ground by the Manasseh Hill country surveyors and by our team were dated to the Iron Age I, as well as flintstone of the Neolithic period.

![]() Fly around the hill with this YouTube video. The drone climbs up above the center of the ruin, looks up to the north, turns to the east and around to view the valley on the west side.

Fly around the hill with this YouTube video. The drone climbs up above the center of the ruin, looks up to the north, turns to the east and around to view the valley on the west side.

Video and photos captured on June 2022

(e) Kh. Umm Ghazal

The Iron Age II fortress was relocated to a closer site on the south side of the valley. It is named Kh. Umm Ghazal but also Khirbet esh-Shakk, same as the Byzantine period village across the valley.

It is located on a raised hillock on the south-east side of the valley. The view, captured by a drone, shows the area of the site from the south.

The fortress covered an area of 2 dunams. It is 15m above and 70m away from the valley, making it easier to fetch water from the spring.

An illustration of the fortress is seen here, with a round tower on the west side, and the rectangular structure on the east side.

Figurative illustration – Iron Age II fortress

The following photo shows a ground view of a section of the site:

Round Tower:

In the center of this fortress was a 20m diameter circular tower. It is composed of 3 round walls, with separating walls between them creating chambers. The external walls are 1m in width, while the inner walls are 0.8m wide and separated by ~2m. The entrance is on the east side.

This aerial view is from the east side.

This type of a round tower was not found in the lands west of the Jordan river prior to the Hellenistic period, except to 2 sites (listed below) that were also built on roads leading to Samaria from the east. According to the article by Adam Zertal, round towers were used in the Iron Age II kingdom of Ammon, so these towers used Ammonite plans.

Garrison:

The base of a 10x15m rectangular structure, with 7 inner rooms, is located on the east side close to the tower. It served as the fortress garrison. Its entrance is on the western side, facing the tower. The walls are 0.4m in width.

A section of the structure is see here from the west side.

Sections of a casemate wall were found on the east side, a few meters from the rectangular structure. This wall may have surrounded the entire fortress. Remains of this wall are seen on the north and south hillsides.

Cisterns:

A number of cisterns and agriculture cup marks are found on the east side of the fortress, although the MHCS stated that there were none.

Note that recent Illicit digging was observed in some of the cisterns, such as in front of this one, and also in a burial cave on the hill south of the site.

Ceramics were dated by the Manasseh Hill Country Survey (MHCS) team to the Iron Age II (80%) and III (20%). They are similar to pottery from Shechem and Samaria city, but different from pottery collected on nearby Hammath.

Similar Iron Age II fortresses were found on other stations along the routes from the Jordan River to the hill country of Samaria: el Makhruq at the entrance to Nahal Tirzah (MHCS, Volume 2, site 269) and Rujm Abu-Mukheir on the road ascending from Fazael brook (MHCS, Volume 5, site 5). Check Adam Zertal’s articles on Iron Age fortresses.

![]() Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Video and photos captured on July 2022

![]() Watch our survey at the site (conducted Aug 2025):

Watch our survey at the site (conducted Aug 2025):

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- esh-Shakk (also: esh-Shukk, esh-Shaqq, es-Saqq) – a claft (split, divided)

- Muntar, Munttar – Arabic: watch tower (same as Hebrew root: Noter – watch)

- Muntar esh-Shakk – the watch-tower of the gorge

- Wady el Maleh – Arabic: the salt valley (named after the hot springs)

- Umm Ghazal – Arabic: mother of Gazelles

Links:

* External links and references:

- “The Manasseh hill country survey” Volume 2 [Adam Zertal , ISBN 965-311-012-8, 1996, pp. 251-259, Hebrew]

- Site 81: Khirbet esh-Shaqq -On a ridge north of the valley; Byzantine period, 15 dunams

- Site 82: Khirbet Umm Ghazal (Kh. esh-Shaqq) – Eastern ridge near the valley, Iron Age 2 and 3, 2 dunams

- Sites 83: Muntar esh-Shaqq – On a high peak, Iron Age 1 II-III, 1 dunam

- “The Roads and highways of ancient Israel” (Dorsey, 1991) – The Bronze and Iron age road is numbered #S14 (p. 173)

- “From Watchtowers to Fortified Cities” — On the History of Highway Forts in the Israelite Kingdom” -A. Zartal, Qadmoniot 1988), pp. 82-86 (5 pages)

- Three Iron Age Fortresses in the Jordan Valley and the Origin of the Ammonite

Circular Towers – Israel Exploration Journal , 1995, Vol. 45, No. 4 (1995), pp. 253-273

* Internal Links:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- Tel Hammath – nearby site

- Khirbet Makhruk – an Iron Age circular tower

- Rujm Abu Mukheir – another Iron Age circular tower

- Tell Abu Sus and Sakut – river crossing

BibleWalks.com – “Arise, walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it…”

Burj el-Maleh <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next site—>>> Qa’un

This page was last updated on Sep 6, 2025 (add Robinson)

Sponsored Links: