An impressive Biblical Tel located near the southern entrance to the Beit Shean valley.

Home > Sites > Jordan Valley > Tel Hammath (Tell el-Hammah)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial Views

* Ascent

* Summit

* Panoramic

* Springs

* Findings

* Burial caves

* Video

Etymology

Links

Background:

Ruins of ancient Hammath are located on Tell el-Hammah, on the side of Highway 90 near the southern entrance to Beit Shean valley.

Location:

The site is located on the side of Highway #90, 700m north west of north of Mehola junction. This impressive mound, with ruins of multiple Bronze and Iron age cities, rises 35m above the plain, covers 30 dunams at its base and 5 dunams on its summit. The summit is at the height of 100m under sea level. On the east side of the mound, closer to the highway, is a low terrace – perhaps remains of the lower city.

The mound is located in a small valley – Wadi el-Hamme. It cuts along the north-western foothills and continues eastwards to the Jordan river. Two springs are on its south west sides: the west spring is the main source of water, while a thermal spring is located in the valley south of the Tel.

Around the spring, on the north, west and south sides of the mound, are ruins of khirbet el-Hamme – a Byzantine, Early Muslim and Mameluke period village.

History:

On this steep mound are at least 17 settlement phases dating from the Early Bronze Age I-II (3rd Millennium BC) to the Early Islamic period (8th-9th century AD). The majority of ceramics that were collected on the surface were dated to the Iron Age (12th-7th century BC). Hammath is named after one of the two springs on its southern side that provided water to the ancient city – a thermal spring.

Bronze Age:

In the beginning of the Late Bronze period the area was conquered by the Egyptians. The Egyptian presence in Beit Shean valley started in 1468 BC after the conquest of Thutmose III (reigned 1479 – 1425 BC). The Egyptian presence was recorded in Tel Beit Shean’s levels IX-VII. On Tel Hammath the excavators did not focus on this period, but in square H6 they unearthed the MBII city walls and glacis.

- Seti I (~1294-1279 BC)

During the reign of Pharaoh Seti I (~1294-1279 BC) a coalition of several rebelling Canaanite cities attempted to seize the headquarters in Beit She’an. Hammath allied with Pella (Pehel) to defeat the Egyptian force in Beit Shean and besiege Rehob. The Egyptians sent three divisions to the Jordan valley – one to crush Hammath, the other to retake Beit Shean, and the third to take Yanoam (perhaps another rebelling city).

This victory is commemorated on a basalt stele that was found in 1928 on Tel Beit She’an, bearing the name of the city (on lines 15 and 19). It reads:

“That day one came to speak to his majesty as follows: “The wretched enemy who was in the city of Hammath he had collected to himself many of people. Was taking away the town of Beit Shean. Then, in league with them of Pehel, he does not permit the chief of Rehov to come outside. Thus, his

majesty sent the first army of Amen, “Powerful Bows,” to the town of Hammath, the first army of the Ra, “Many Braves” to the city of Bethshan,

and the first army of Sutekh, “Strong of Bows,” to the city of Yanoam. It happened in the space of one day that they were overthrown by the will of his majesty”.

The Egyptian rule of the area ended in the Late Bronze period.

A replica of Seti I stele in Beit Shean

Iron Age:

- Israelite period (the Judges)

The mighty Canaanite city was probably not conquered by the Israelites during their conquest of Canaan in the 12th century. Although the Bible does not name the city directly, it does tell us that the region of Beit She’an remain Canaanite (Judges 1: 27):

“Neither did Manasseh drive out the inhabitants of Bethshean and her towns“.

- Israelite period – Unified Kingdom (Saul, David, Solomon)

Even the first Israelite King Saul did not manage to take this small Canaanite enclave around Rechov and Beit She’an. Only his successor, King David, managed to take it in approximately year 1000 BC, extending his empire to the upper Galilee. Since then, the area was under the control of the Israelites. (1 Chronicles 18 3):

“…And David smote Hadarezer king of Zobah unto Hamath”.

Note that this city, Hamath, has the same name as this site, but actually it is a major city in Syria. Aram-Zobah is yet another city in Syria.

King Solomon appointed a governor in the area (1 Kings 4:12):

“Baana the son of Ahilud; to him pertained Taanach and Megiddo, and all Bethshean, which is by Zartanah beneath Jezreel, from Bethshean to Abelmeholah, even unto the place that is beyond Jokneam”.

Abel Mehola is a place near a river-crossing ford of the Jordan river, 6km to the east of Hammath. Later it was the home town of prophet Elisha (1 Kings 19:16).

- Israelite period (Northern Kingdom)

In 928 BC, after Solomon’s death, the Kingdom separated to the south (Judah) and the north (Israel), and Rechov and its towns (including Hammath) became part of the Northern Kingdom.

- Shishak’s conquest

After Solomon’s death and following the weakness of the new Kingdoms, Egypt’s Shishak invaded Israel in 924 BC (1 Kings 14: 25):

“In the fifth year of King Rehoboam, Shishak king of Egypt attacked Jerusalem”.

The force in this invasion was detailed in Chronicles (2 Chronicles II 12:2-3):

“And it came to pass, that in the fifth year of king Rehoboam Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem, because they had transgressed against the Lord, With twelve hundred chariots, and threescore thousand horsemen: and the people were without number that came with him out of Egypt; the Lubims, the Sukkiims, and the Ethiopians”.

According to the Pharaoh’s hieroglyphic inscriptions, Beit Shean and Rechov are listed as one of the cities that he captured and Beit Shean’s governor is illustrated as led to captivity in Egypt. This was probably the fate of Hammath.

Karnak: Commemoration of Shishak’s victory over Rehoboam

Photo of the Library of congress (American Colony, taken 1900-1920)

Biblical map

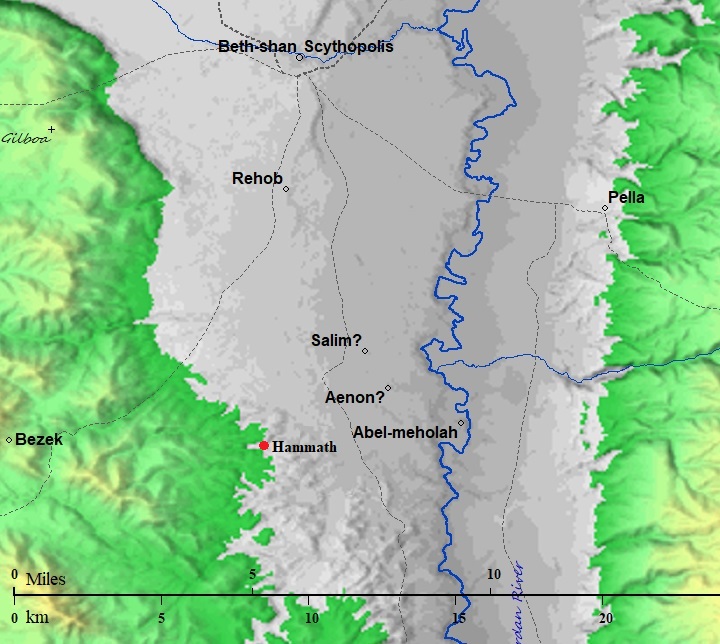

The cities and roads during the Canaanite and Israelite periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below, with Hammath (Tel el-Hammeh) marked by a red dot. This strategic city guarded major ancient routes from Samaria to Tel Rechov (Rehob) and Beit Shean (most important sites in this region) and to TransJordan via the fords along the Jordan river near Tell es-Sakut.

Another ancient road to Jericho and to Samaria passed on the side of the site, but is not shown here.

Map of the area around Tel Hammath- during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

David Dorsey (“The roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”, 2018) shows a detailed map of the roads around the site during the Bronze/Iron age. The main road from Rechov/Rehob southwards is marked as A3. It passes Tel Malqoah, 3km north of Hammath, where the road splits to two routes towards Shechem and Samaria:

- route S13 – via Qa’un, along Wadi el Khashneh, to Aser (modern Tayasir) and Thebez (Tubas)

- route S14 – After passing Hammath, it continued south along the foothills to Ras el-Humeiyier. It then turned south west thru the valley of esh-Shukk, where a pair of Iron Age fortresses guarded the road, and continued west along Wadi Malikh to join route S13.

Another route (“T9c”) from Hammath and Ras el-Humeiyier turned east towards the crossing point on the Jordan river at Tel Abu Sus (marked ‘Abel Mehola’ on the map), via Kh. ein Sakut (Biblical Sukot) which guarded the crossing point.

City Plan

Three archaeological seasons, headed by J. Cahill, G. Lipton and D. Tarler (1985-1990), were conducted on a single 360 m² area (‘A’) under the south eastern side of the summit. Due to the steep slope (30 degrees), the excavations were conducted in four terraces (excavation squares J, K, L, M) and trial terraces (H-G). The archaeologists focused on the Iron Age levels.

At least 3 levels of Iron Age were destroyed by fire. They ranged from the 11th century to the late 9th/early 8th century.

Terrace M revealed a stone structure and a mud brick structure, dated to the Iron Age IIc (8th-7th century BC). It was built over a destruction level 9th-8th century.

In the lowest Terrace L, under level M, a 4-room Israelite house was unearthed, dated to the 10th century BC. In the room, with a stone floor, they found 40 pottery jugs, pots and other items. It was found to be destroyed by fire, and was built over a previous level that was dated to the 10th century. The excavators attribute this destruction either to the conquest of King David or to the conquest of Egyptian Shishak (924 BC).

The excavations in grid H6 revealed a section of the ramparts, including a 2.6m wide wall along the -115m height, and an external glacis. They concluded that the area within the city walls was much larger – 13 dunams during MBII period (20th-17th century BC). The walls were mostly made of mud bricks, as few stones are seen on the hill.

The area of the gate was assumed to be on the south east side, where there is a deep ravine in the foothill that separates the mound into two equal sizes.

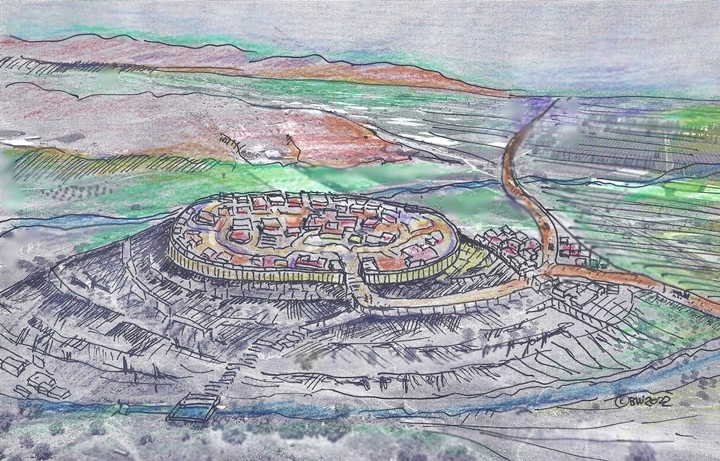

A figurative illustration of the city during the Israelite period is shown here. Although only future excavations will provide solid inputs on the features of this site, some of the highlights are assumed and illustrated here.

Biblical period – figurative illustration of Hammath

Roman period

An ancient Roman highway passed on the east side.

Byzantine, Early Muslim, Mameluke

A Byzantine period village was established in the valley and foothills around the spring of Ein el-Hammah, south of the abandoned mound. It continued to be settled at later periods.

Later periods

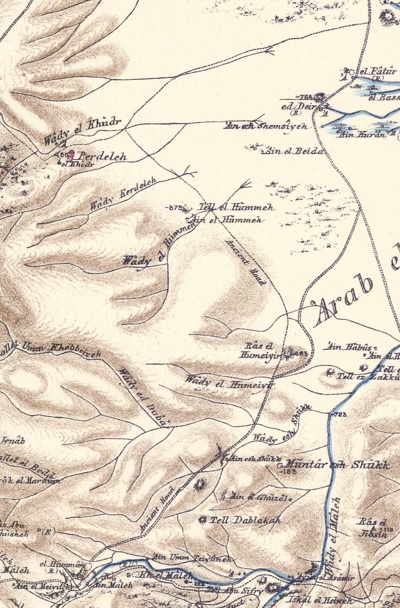

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their map shows Tell el Hammeh along an “ancient road”. Their report of Tell el Hummeh was short (SWP, Vol. 2, p.246): “A large artificial mound near a good spring”.

They detail the road (p.232): “The road from Nablus [Shechem] to Beisan [Beit Shean], through Wady Beidan … The southern branch runs east from Teiasir down Wady Maleh, and is marked in places by side walls. At ‘Ain Maleh it gradually turns north-east, and joins the Jordan valley road east of Tell el Hummeh…”.

Part of Map sheet 12 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

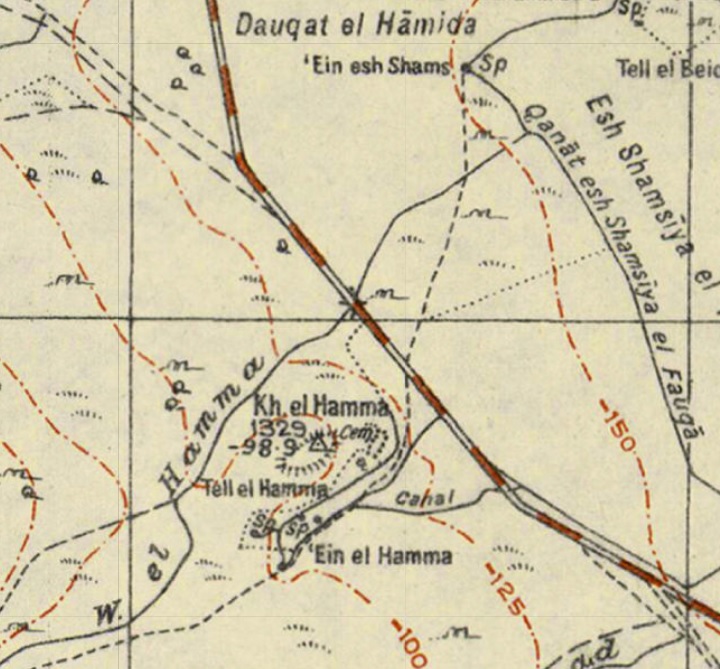

British Mandate

A 1940s British map shows the area around the site with more details. Notice the 2 springs, and the two sites – the Biblical Tel (Tell el Hamma) and the Byzantine village (Kh. el Hamma). The road from Baisan (Beit Shean) to Jericho passes at the side of the site, as does the modern highway #90.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

Modern Times

The site is within area C (full Israeli control of security, planning and construction) in north east Samaria, close to the checkpoint on highway #90. Around the site is small scale Bedouin farming.

Photos:

(a) Aerial views

A drone captured views of the site from different angles. This view is from the north side.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

Another view from the south side:

A view from the east is next.

Remains of structures are visible at the eastern foothills – perhaps this was a section of the lower city.

Yet another view from the east, but at higher altitude:

A view over the summit is next. The orientation is the west side is on the top.

Notice the ravine on the south east side that cuts into the foothill.

(b) Ascent

The following is a ground view of the Tel from the north side. Along the foothills are some old tracks of vehicles that tried to brave the slopes, but failed to reach the summit. Only the west and east slopes tracks were successful in reaching the top.

The slope was too steep for our 4×4 vehicle, as the ground along the old tracks was too loose. So we left the vehicle at the bottom of the hill.

We ascended by foot to the top of the hill from the west side.

Here, Uncle Ronnie used a pair of Nordic walking sticks to be able to climb up the loose ground. Actually, climbing up (and down) was made easier along the foothills outside of the tracks.

(c) Summit

The summit is flat and bare. The interesting parts are the foothills around the summit. This aerial view from the north east shows the view of the summit.

A ground view of the summit is in the next photo, facing the Jordanian mountains in the east.

Next: A view from the summit towards the west.

The houses seen here in the background are farmers that grow sheep and goats.

In the center of southern foothills is a depression that cuts into the ground and splits the summit into two sections. This may have been the location of the gate to the city.

(d) Panoramic Views

From the summit are great views of the area.

a. South

The following is a view from the summit towards the south. Highway #90 continues south along the Jordan valley, down to Jericho.

In the center of this view is Mehola junction, just 400m south of the mound, with a turn towards the west (in direction of Samaria). The modern road uses the same route (Milha valley) that was used in ancient times to get to Shechem and Samaria. Tel Hammath was built here to guard this junction.

2. East

The next view, turning slightly northwards, shows the Arab village of Tell esh-Shemsiyeh. In its center is the minaret (Arabic: beacon) – mosque tower.

In the far background is the valley of the Jordan river and the TransJordanian mountains.

3. North

The next view, turning again northwards, is highway #90, in direction to Beit Shean.

(e) Springs

The two springs, cold and hot, are located in the valley to the south west of the mound.

Below is the view of the main spring on the south west side of the mound.

The first pool is covered by water plants. It feeds a modern cement aqueduct with a pipe at its end.

The second pool is an open pond.

(f) Findings

Bronze and Iron age pottery are visible around and on the hill. The foothills are covered by a blanket of pottery fragments.

Archaeologist Ayelet Goldberg-Keidar helped to research the site and identify the pottery scattered on the surface. Here and there were interesting parts we have examined during our brief visit on the mound.

The following are few samples of interesting findings. All items were returned to their original location.

1. One of the pottery fragments had a sign scratched on the handle. A potter’s mark is typical of Iron Age pottery.

2. Another piece of pottery was dated to Iron Age II period (10th-9th century BC):

3. Yet another pottery, dated to Iron Age II period (10th-9th century BC):

4. A handle, dated to the Byzantine period:

5. A fragment of a glass, probably dated to the Byzantine period.

6. An Iron age period fragment:

7. A potter’s mark with double plus signs on an Iron Age pottery handle

(e) Burial caves

South of Tel Hammath is the main necropolis of the city. Dozens of burial caves are cut into the hill.

Most of the burial caves were looted… illicit digging is even happening in recent times. In some caves you can see buckets used to carry out the soil that they sift thru.

(f) Video

![]() Fly around the site with this YouTube video. The drone surrounds the Tel starting from the east side.

Fly around the site with this YouTube video. The drone surrounds the Tel starting from the east side.

Video and photos captured on June 2022

Etymology (behind the name):

- Tel (Tell) – mound (See more on the story of a Tel).

- Hammath (חמת)- based on Hebrew root – Ham (חם hot). Named after one of the two springs on its southern side that provided water to the ancient city – a thermal spring.

- Mehola (מחולה) – nearby Moshav community, established 1969. Named after Abel-Mehola – a nearby Biblical city and birthplace of prophet Elisha (1 Kings 19:16: “Elisha the son of Shaphat of Abelmeholah shalt thou anoint to be prophet in thy room”.).

Links:

* External, archaeological links:

- Crossing the Jordan river during the Biblical period – north versus south – David Moster, Aram 29 (2017), pdf

- Late Bronze Survey in Jordan valley – James Mark Schaaf (545 pages, 2012, thesis, Univ S. Africa); great resource!

- Survey of Tel Rechov area – Ahia Cohen-Tavor , 2010, Hebrew Univ, Hebrew

- Seti I stele – Alan Rowe, Penn Museum

- “The Manasseh Hill country survey” – Volume 2 – The Eastern valleys and the Fringes of the desert – Adam Zertal (ISBN 965-311-012-8; Hebrew; 1996)

- Site 66: Wadi el-Hamme

- Site 67: Khirbet el-Hamme

* Internal links:

BibleWalks.com – exploring the ancient sites of Israel

Tells Abu Sus and Sakut<<<—previous site—<<< All Sites>>> — Next site—>>>Saul’s shoulder

This page was last updated on Mar 1, 2024 (add pottery mark)

Sponsored links: