Ruins of a large multi-period village, located on the eastern slopes of Mount Gilboa.

Home > Sites > Jordan Valley > Tell Migda’ (Khirbet el Mujedda)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Ground views

* Findings

* Spring

* Ridge

* Excavations

Etymology

Links

Background:

On Tell Migda’ (Khirbet el Mujedda) are ruins of a large (125 dunam) multi-period village, located on the Eastern slopes of Mount Gilboa. On the north side is the Revaya spring (‘Ain el Mujedda’a) which was the main source of water. On and around the site are flintstones, pottery fragments, traces of structures and walls, basalt stones, cisterns, burial caves and a Byzantine-period aqueduct.

Location:

This map shows the area around the site. It is located 2 kilometers NW of Moshav Revaya.

History:

The multi-period site was inhabited since the Bronze age.

Surveys dated the settlement to the Early and Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age, Persian, Roman/Byzantine (Major period), Early Islamic and Ottoman periods.

-

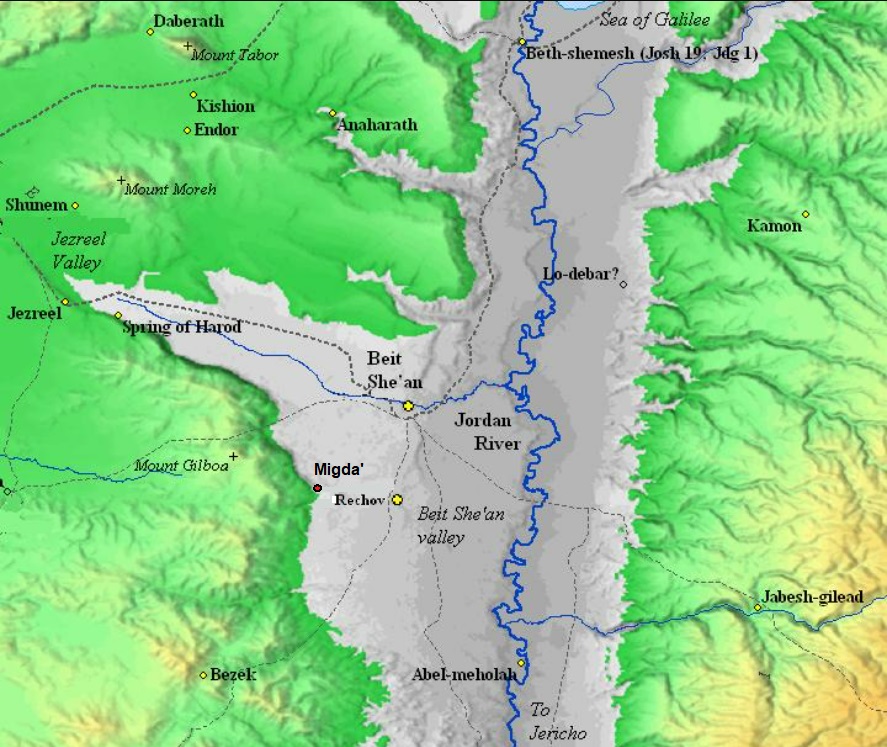

Biblical map

The cities and roads during the Canaanite and Israelite periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below, with the site marked by a red circle.

Map of the area of Jordan valley around the site (red circle)- during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

Although not indicated o0n this map, an ancient Bronze/Iron age road descended thru the village. According to Dorsey, this route was named “T11a”. It connected Jenin (Beth-Haggan/Ein Ganim in Samaria), via Beit Kad and Jalbun, down to the Jordan valley, and passing thru the village.

In our survey we noticed remains of a pair of round towers, probably dated to the Iron Age, above the north side of the valley where the road passed. This seems to us like a pattern of erecting fortresses or towers along routes connecting the hill area to the valley, such as we found in many other cases in the Beit Shean area.

-

Ottoman period

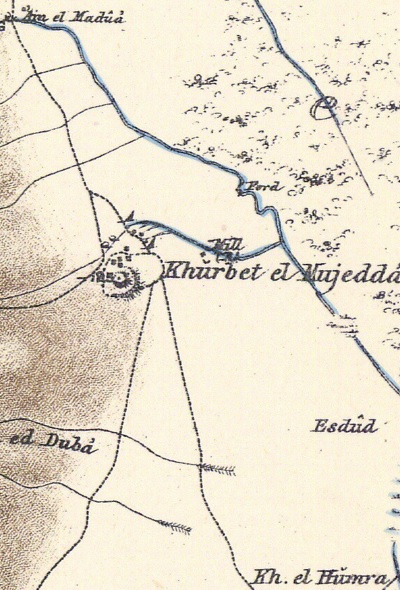

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. They merely wrote about the site (Volume 2, sheet IX, p.122):

“Khurbet el Mujedda —Traces of ruins only remain upon a mound of debris ; but the place has the appearance of an ancient site and fine springs”.

Note that Conder suggested that the famous city of Megiddo was located here in Khirbet Mujedda rather than Tell el-Mutesellim (Tel Megiddo in the Jezreel valley).

A section of the survey map is shown here. The site is illustrated as a two-heap mound. The spring (Ein Revaya) is marked on the north side of the mound and has a number of sources. The road descending from Mt. Gilboa is marked here on the south bank of the valley above the site (that appears on the British map as Wadi abu Ghazal).

Part of Map sheet 9 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

In addition to the illustration of the site, the map indicates that there was a flour mill to the east of the site. It used the power of the water to grind the grains of the wheat grown in the farming fields.

A ford is also marked on the creek flowing from ‘Ain el Madua (a spring 2km west of Reshafim). It was used to cross the Nahr el Maddu creek on the road to the Jordan river crossing in Kfar Ruppin, as well as north/south directions.

- British Mandate

In 1938 forces of the Special Night Squads, headed by Orde Wingate, attacked the village where a terrorist gang was hiding.

In 1948, during the Independence war, two soldiers died here while attacking expeditionary forces from Iraq.

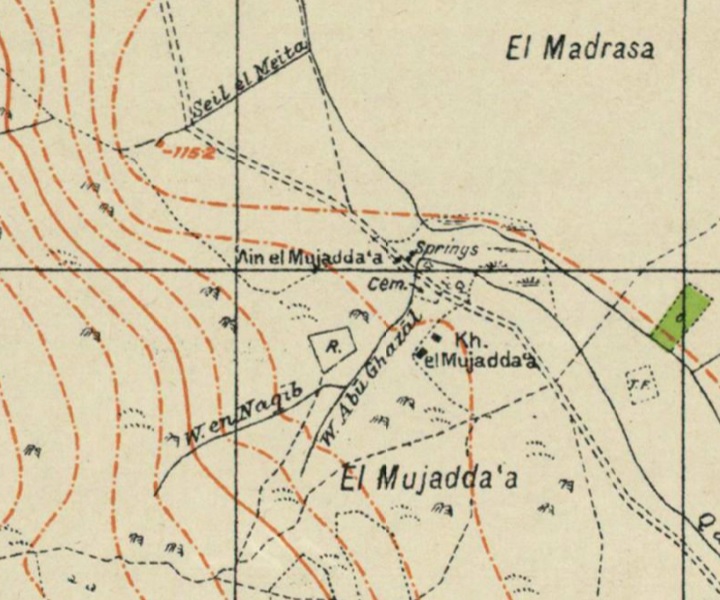

A 1940s British map shows the area around the site with more details. Notice a cemetery (“Cem.”) is marked on the north side of the mound.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

-

Modern Times

A modern basalt query, as well as military works and development activities, damaged the site. It is yet not thoroughly excavated, except for limited emergency excavations.

The site is in an open public place.

Photos:

(a) Aerial Views

A drone captured this view towards the south. The site is located on and around the mound, spread over 125 dunams. On the far left side is the Jordan valley, while on the right side are the foothills of Mt. Gilboa.

On the north east side, here on the bottom left, is the green area of the springs.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The next drone photo is a view towards Mt. Gilboa on the west side. A road descended from the Gilboa heights thru the village unto the Jordan valley.

- Flight over the site:

![]() Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

Fly above and around the site with this YouTube video.

The drone scans the site starting from the southern foothills side, turns around the eastern side of the hill, then around to view the Sea of Galilee.

(b) Ground Views

Most of the mound is bare, as the bases of the structures were covered by soil over the centuries, and most of the architectural elements were robbed. However, during our survey we did see some sections of walls, cisterns and caves, basalt building stones, and pottery fragments.

On the north side of the mound are many caves and cisterns, such as this one. In these hot areas the underground caves were used as a cooler extension of the houses, for storage and for water reservoirs.

A view inside this cave is below…

Since it is covered by accumulation of soil, it is difficult to see the full extent of the cave.

Yet another cluster of caves, with some sections of walls:

In this cave is an inner tunnel, perhaps a hiding complex.

On the south side of the mound is a wide road or street, with a line of stones along its edge. It leads towards Mt. Gilboa.

(c) Findings

- Basalt tools

Basalt stone is the primary type of stone found on the mound. The strong Basalt stone was used as a building material and for installations due to it durability, strength, and resistance to weathering. For example, this carved stone on the south side of the mound:

Basalt’s hardness and toughness made it suitable for crafting various tools and weapons. Ancient peoples shaped basalt into axes, hammers, grinding stones, and cutting tools. It was particularly valued for its ability to hold a sharp edge and its resistance to wear and abrasion.

The following basalt stone was used as a grinding stone:

It is also a valuable commodity in modern times. On the south west of the site is a modern basalt stone quarry.

- Glassware

As a complete opposite to the hard basalt stone, glass is delicate and decorative. The Romans were skilled in glass production and created a wide range of glass objects for both practical and decorative purposes.

During our survey we noticed many fragments of Roman/Byzantine glassware. Glass vessels are representative of the Late Roman and Byzantine period (as per Gorin-Rosen).

- Ceramics

Past surveys (N. Zori 1977, Achia Cohen Tabor 2020) dated the settlement to the Early and Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age, Persian, Roman/Byzantine (Major period), Early Islamic and Ottoman periods. The dating were primarily based on pottery fragments.

In our short survey on the mound, led by archaeologist Ayelet Goldberg-Keidar, we have dated all the ceramics we collected to the Roman/Byzantine periods.

A closer view of one of the Roman/Byzantine handles:

(d) Revaya Spring

On the north east side of the mound is the Revaya perennial spring (‘Ain el Mujadda’a). Its name attests to its characteristics – “Revaya” means in Hebrew “overflowing” or “saturated”.

Around the spring is a large area of Rubus Sanguineus bushes (Hebrew: Petel Kadosh), loaded with fruits or flowers (depending on the season).

A number of large Sheizaf trees (Ziziphus spina-christi) enjoy the waters of the spring. The water level of the spring can be seen in the bottom of the cement tubes that were drilled at the side of the trees.

(e) Overlooking hill

On a ridge overlooking the site is what we consider as an observation place. From this position are great sights of the area, and during antiquity it was probably used to watch for movements in the Jordan valley, protect the route to Samaria, and exchange fire signals with the main cities in the area (such as Rechov).

We noticed 2 possible places of towers – on the north and south side of the ridge.

This round tower, probably dated to the Iron Age, is on the north side. Only the base of the tower remained. Its upper side was probably made of basalt stones that were removed or fell inside, and by mud bricks that have since crumbled.

As seen from above, the diameter of the base of the tower is 10m.

(f) Excavations 2024

The electrical company is building a new high-voltage line that will support the growing supply of solar and hydropower plants that has been added in the Jordan valley area. The electrical line crosses the site and a high pole is planned at the edge Tel Migda. An IAA team is engaged in emergency archaeological excavations to determine the effect of the construction of a concrete base for the pole. Several areas were opened in the planned area of the construction of the pole’s base.

Etymology (behind the name):

- Tel (Tell) – mound (See more on the story of a Tel).

- Khirbet el Mujadda – Ruin of the cropped or cut-off place. (as per PEF dictionary)

- Revaya – Hebrew for “overflowing” or “saturated”

- Moshav Revaya – community near the site, founded 1952

Links:

* External, archaeological links:

- Survey of Western Palestine, Vol 2 Sheet XII

- Survey of Tel Rehov area in the Beit-Shean Valley, Ahia Cohen-Tabor 2010; sites 25-26 pp. 62-63

- The Land of Issachar, N. Zori 1977, site 46

- Horbat Migda’ Ha-eSi 132 2020 – Abdalla Mokary

- Gorin-Rosen Y. 1999. The Glass Vessels. In D. Syon. A Roman Burial Cave on Mt. Gilboa. ‘Atiqot 38:63*–68* (Hebrew; English summary, pp. 225–226).

* Internal links:

-

Tel Rechov – The main Iron age city in the area

BibleWalks.com – unearthing the Bible lands

Dalhamiya<<<—previous Jordan Valley site—<<< All Sites>>> — Next site—>>>Archaeological survey

This page was last updated on Oct 3, 2024 (excavations)

Sponsored links: