An overview of ancient hiding places. Psalm 27:5: “For in the day of trouble he will keep me safe in his dwelling; he will hide me in the shelter of his sacred tent and set me high upon a rock.”

Home > Info > Hiding Complexes

Contents:

* Overview

* History

* Construction

* Why Hide?

* Sites of hiding places:

** Judea

** Samaria

** Galilee

* Etymology

* Biblical

* Links

Overview:

Hiding complexes in ancient Israel, often referred to as “refuge caves”, were underground systems used for protection during times of conflict and invasion. These complexes played a crucial role in the survival strategies of the Jewish population during periods of unrest, particularly during the Roman occupation and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 AD). Here are some key aspects:

Purpose and Usage

- Refuge during Revolts: These complexes were particularly used during Jewish revolts against Roman rule. The Bar Kokhba Revolt saw extensive use of such hiding places.

- Protection from Raids: They provided refuge from invading armies or raiding parties, allowing inhabitants to hide and survive in hostile environments.

Structure and Features

- Underground Complexes: These were often elaborate underground systems consisting of narrow passageways, storage chambers, water cisterns, and living quarters.

- Camouflage: The entrances were typically well-hidden, camouflaged by natural landscape features or concealed within existing structures like homes or public buildings.

- Self-Sustaining: Many had provisions for long-term habitation, including food storage facilities, water sources, and ventilation systems to support life underground for extended periods.

Archaeological Evidence

- Excavations: Archaeological excavations have uncovered numerous hiding complexes across Israel, particularly in areas like Judea and Galilee. Sites like Horvat ‘Ethri and the Bell Caves of Beit Guvrin have revealed extensive networks.

- Artifacts: Pottery, coins, and other artifacts found within these complexes help date their use and provide insights into the daily lives of those who used them.

Historical Context

- Roman Conquest and Rebellions: The necessity for such complexes arose from the harsh realities of Roman conquest and the suppression of Jewish revolts. The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD and subsequent revolts made these refuges critical for survival.

- Resistance Strategies: The hiding complexes represent a broader strategy of resistance, where guerrilla tactics and underground networks were employed against a powerful and oppressive occupying force.

Modern Discoveries

- Ongoing Research: New hiding complexes continue to be discovered, providing further insights into the ancient strategies of concealment and survival.

- Technological Advances: Modern archaeological techniques, such as ground-penetrating radar and 3D modeling, have enhanced our ability to locate and understand these complexes.

Significance

- Cultural Heritage: These hiding complexes are an essential part of Israel’s cultural and historical heritage, showcasing the resilience and ingenuity of ancient Jewish communities.

- Tourism and Education: Many sites have been preserved and are accessible to the public, serving as educational resources and tourist attractions that highlight this fascinating aspect of ancient history.

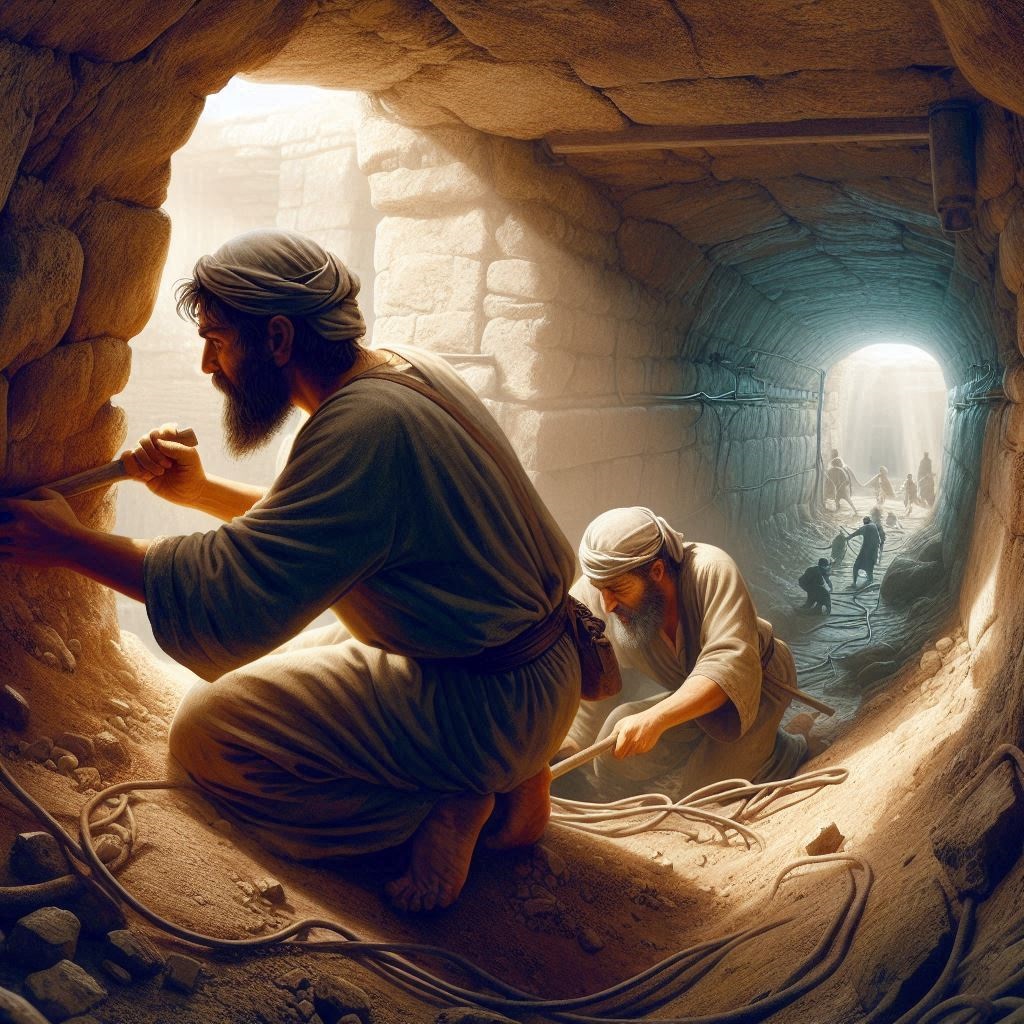

Digging underground hiding complexes – AI generated by Stable Diffusion

In summary, hiding complexes in ancient Israel were sophisticated underground refuges used during times of conflict to protect the local population. They are a testament to the resilience and resourcefulness of ancient communities in the face of adversity.

History

The history of hiding complexes in ancient Israel is intertwined with the region’s tumultuous history, marked by invasions, wars, and uprisings. These complexes reflect the strategies and resilience of the Jewish population during periods of significant conflict, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Here’s a detailed overview:

Early Developments

- Biblical Period: While there is limited direct evidence of hiding complexes from the biblical period, the idea of using natural caves and man-made hideouts for refuge is noted in various historical and biblical texts. For instance, David hid from King Saul in the caves of En Gedi.

- Hasmonean Period: During the Hasmonean period (2nd century BCE), as the Jewish state sought independence from the Seleucid Empire, fortified sites and hideouts became essential for guerilla warfare. These early strategies set the stage for more sophisticated hiding complexes in later periods.

Roman Period

- First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE): The First Jewish-Roman War led to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. This period saw the emergence of more organized hiding complexes as Jewish rebels and civilians sought refuge from Roman forces.

- The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 CE):

- Background: This was the third major rebellion by the Jews against the Roman Empire and led by Simon Bar Kokhba. It was a direct response to Roman policies, including the establishment of Aelia Capitolina and the banning of circumcision.

- Hiding Complexes: The Bar Kokhba Revolt significantly increased the use of hiding complexes. These were often built beneath towns and villages, featuring intricate networks of tunnels, rooms, and storage areas. The complexes were used to hide from Roman soldiers and as bases for launching guerrilla attacks.

During the second (Bar Kokhba) revolt in the 2nd century AD, Jewish residents across most of the villages in Judea tried to save themselves by constructing underground hiding places. Most of these rock cut tunnels and chambers were constructed under or near the residential buildings. The Roman historian Cassius Dius wrote about this (Historia Romania, 69, 12, 3):

“To be sure, they did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved under ground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light”.

Post-Revolt Period

- Roman Suppression and Destruction: Following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, many of these complexes were destroyed by the Romans, who sought to eliminate any further resistance. This led to a significant reduction in their use.

- Persistence of Caves: Despite this, some hiding complexes continued to be used intermittently in later periods, including during the Byzantine and early Islamic periods, primarily for local conflicts and banditry.

Modern Discoveries and Archaeological Research

- Rediscovery: Many of these complexes were rediscovered in modern times through archaeological excavations. Researchers have uncovered numerous hiding complexes across Israel, particularly in the Judean and Galilean regions.

- Research Methods: Modern archaeological techniques, such as ground-penetrating radar, carbon dating, and 3D modeling, have allowed for detailed mapping and analysis of these complexes, providing deeper insights into their construction and use.

Cultural and Historical Significance

- Survival and Resistance: Hiding complexes are a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of ancient Jewish communities. They reflect a broader strategy of survival and resistance against powerful occupying forces.

- Cultural Heritage: Today, these complexes are part of Israel’s rich archaeological and cultural heritage. Many sites have been preserved and opened to the public, serving as important educational resources and tourist attractions.

Digging underground hiding complexes – AI generated by Dream by Wombo

In summary, the history of hiding complexes in ancient Israel is a narrative of adaptation and resistance. These complexes illustrate the strategies employed by ancient Jewish communities to survive and resist foreign domination, leaving a lasting legacy in the archaeological record.

Construction Techniques

The construction techniques of hiding complexes in ancient Israel were sophisticated and designed to ensure maximum concealment, functionality, and sustainability. These techniques reflect a deep understanding of engineering, geology, and survival strategies. Here’s an overview of the key construction methods and features:

Site Selection and Planning

- Natural Topography: Builders often chose sites with natural features that could be easily modified or expanded. Caves, hillsides, and rocky terrains were preferred due to their concealment advantages.

- Integration with Existing Structures: Many hiding complexes were integrated into existing homes, public buildings, or agricultural installations. This made entrances less conspicuous and easier to hide.

- Strategic Location: Proximity to essential resources like water and food sources was crucial. Complexes were often situated near water cisterns, agricultural fields, and storage facilities.

Hiding in natural caves (Image created by AI using DALL·E through OpenAI’s ChatGPT).

Excavation and Construction Techniques

- Manual Excavation: The primary method for creating these complexes involved manual excavation using tools like chisels, hammers, and picks. Workers painstakingly carved out tunnels and chambers from the bedrock.

- Layered Excavation: Excavation often proceeded in layers to ensure structural stability. Builders started with a central chamber or passage and then expanded outward, adding more rooms and tunnels.

- Reinforcement: In some cases, walls and ceilings were reinforced with wooden beams or stone slabs to prevent collapse. This was especially important in larger complexes.

Architectural Features

- Narrow Entrances and Tunnels: Entrances were kept narrow and concealed to make detection difficult. Tunnels were often winding and narrow, restricting movement and making it hard for invaders to navigate.

- Hidden Entrances: Entrances were cleverly disguised with natural elements like rocks, soil, or vegetation. Some were hidden under removable stone slabs or within false walls.

- Multiple Chambers: Complexes typically featured multiple chambers, including living quarters, storage rooms, and escape routes. This ensured that inhabitants could move and hide if one section was discovered.

Ventilation and Lighting

- Air Shafts: Ventilation shafts were incorporated to provide fresh air to the inhabitants. These shafts were often narrow and disguised on the surface to avoid detection.

- Smoke Management: Complexes included smoke outlets or concealed chimneys to manage smoke from cooking or heating without revealing the complex’s location.

- Lighting: Oil lamps and small torches provided lighting within the complex. Care was taken to ensure that light did not escape to the surface.

Water and Food Storage

- Water Cisterns: Many complexes had built-in water cisterns or were located near natural water sources. These cisterns were essential for sustaining life during long periods underground.

- Food Storage: Storage rooms were designed to keep food supplies, often sealed to protect against moisture and pests. Ceramic jars and other containers were used for storing grains, dried fruits, and other non-perishable foods.

Security and Defense Mechanisms

- Booby Traps: Some complexes included booby traps such as pits or concealed spikes to deter or injure invaders.

- False Passages: To confuse attackers, builders often created false passages and dead ends.

- Escape Routes: Complexes frequently had multiple exits or escape routes leading to different locations, allowing inhabitants to flee if discovered.

Modern Implications

- Preservation and Study: Modern archaeological techniques, such as 3D scanning and ground-penetrating radar, help researchers study these complexes without extensive excavation, preserving their integrity.

- Cultural Heritage: These complexes are vital for understanding the historical and cultural context of ancient Israel, providing insights into the daily lives, survival strategies, and resilience of its people.

Digging underground complexes – AI generated by Bing

In summary, the construction of hiding complexes in ancient Israel involved careful planning, sophisticated engineering, and a deep understanding of the natural landscape. These techniques ensured that the complexes were well-hidden, secure, and capable of sustaining life during prolonged periods of conflict.

Why Hide?

Hiding complexes in ancient Israel were used for several reasons, primarily driven by the need for protection and survival during times of conflict and persecution. Here are the main reasons why people hid in these complexes:

1. Protection from Invasions and Raids

- Roman Occupation: During periods of Roman rule, particularly during the Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire, these complexes provided refuge from Roman soldiers who were known for their harsh suppression of uprisings. The First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE) and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 CE) are key examples where such hiding places were extensively used.

- Other Invaders: Beyond Roman incursions, the region faced threats from various other groups over the centuries, including local bandits, rival factions, and foreign invaders. Hiding complexes offered a means to escape immediate danger.

2. Guerrilla Warfare and Resistance

- Tactical Advantage: The complexes served as bases for guerrilla fighters, allowing them to launch surprise attacks against occupying forces and then retreat to safety. The narrow and intricate passages made it difficult for enemy forces to follow and capture them.

- Preservation of Leadership: Leaders and key figures in the resistance movements could hide in these complexes, ensuring continuity and coordination of the resistance efforts even when external conditions were dire.

3. Protection of Civilians

- Safety for Families: Entire families, including women, children, and the elderly, could seek refuge in these hiding complexes during times of conflict. This protected non-combatants from violence, abduction, and other atrocities that were common during invasions.

- Long-term Shelter: These complexes were equipped to support life for extended periods, with provisions for water, food storage, and basic living conditions, allowing civilians to wait out sieges or periods of intense conflict.

4. Preservation of Resources

- Protection of Supplies: Valuable resources, including food, water, and religious artifacts, could be stored in hiding complexes to prevent them from being looted or destroyed by invading forces.

- Economic Stability: By protecting essential resources, communities could better withstand prolonged periods of conflict without facing starvation or economic collapse.

5. Religious and Cultural Preservation

- Sacred Objects and Texts: Hiding complexes were sometimes used to protect sacred objects, religious texts, and other culturally significant items from desecration or destruction by hostile forces.

- Secret Practice of Religion: In periods when practicing Judaism openly was dangerous, these complexes provided a space where religious rituals and traditions could be maintained in secret.

6. Psychological and Moral Support

- Hope and Resilience: The existence of hiding complexes gave the population hope and a means to resist despair during dark times. Knowing there was a safe place to retreat to bolstered community morale.

- Community Cohesion: Sharing these secret spaces and the efforts involved in creating and maintaining them strengthened community bonds and a sense of collective identity.

Historical Context

- Roman Reprisals: Following the suppression of Jewish revolts, the Romans often conducted harsh reprisals, destroying cities, killing inhabitants, and selling survivors into slavery. Hiding complexes provided a last resort to avoid such fates.

- Ongoing Threats: Throughout history, the region faced continuous threats from various conquering armies and internal strife, making the existence of such refuges a recurring necessity.

Roman Soldiers search for hiding rebels – AI generated by Bing

In summary, hiding complexes in ancient Israel were essential for survival during periods of conflict and persecution. They provided protection, facilitated resistance, preserved vital resources and cultural heritage, and offered psychological support to communities under threat.

Hiding places in Biblewalks sites:

(a) Judea

Horvat Shu’a is an archaeological site, situated on a hill on the southern bank of Nahal Shu’a. This site is located 1km east of Moshav Tzafririm, within the Adullam-France National Park, in the area of the low hills (Shephelah) of Judea. Its Arabic name is Kh. Umm el Loz – “the ruin with the Almonds”.

On the summit of the hill are residential complexes with hewn caves, cisterns, installations, columbariums, and a well. The site, covering an area of 5 dunam, was settled from the Hellenistic period, Roman and Byzantine periods. Hiding complexes of the Bar-Kochbah revolt indicate that it was a Jewish village.

Some of the caves are interconnected, forming an underground complex.

A large archaeological site in the Judean Shephelah region, with remains of a rich Early Roman period rural settlement and a Byzantine church.

In Horvat Midras are 10 documented underground hiding complexes, constructed to serve as refuge places during the Bar Kokhba revolt. These were cut into the soft rock, utilizing existing cisterns and underground storage places.

One of the hiding complexes originate in this underground cave. This was an originally a cistern used as a reservoir, and during the Bar Kokhba revolt was converted to a hiding place.

The tunnels were cut into the rock in order to crawl to the hidden chambers where the residents were to flee and stay for a length of time.

The tunnels were intentionally designed to be narrow and have crooked angles, make the crawling more difficult. Along the tunnels were places intended to block the passage. These were planned to deter the entry of the Roman soldier.

Ruins of an Early-Roman Jewish rural village in the Judean foothills region, south of the valley of Elah. The remains include residential houses, cisterns, several ritual baths (Miqveh), ancient synagogue, wine presses and other farming installations.

A rock cut stepped and white plastered installation of a ritual bath (Mikveh) is located on the east side of the public building. It was constructed before the construction of the building, during the Hasmonean period. Later, during the Bar Kokhba revolt, it was used as an entrance to a public hiding complex.

Horvat Rebbo is an archaeological site, situated on a hill between the valleys of Nahal Shua and Nahal Shochah. The site is located 1km west of Moshav Aderet, within the Adullam-France National Park, in the area of the low hills (Shephelah) of Judea. Hiding complexes of the Bar-Kochbah revolt were found on the hill.

The following photo is an opening to a cistern, part of an extensive underground system.

A fortified Tel, situated near an ancient strategic road in the Northern Samaria region.

There are 20 known cisterns on Ferasin. The were built to supply water on top of the hill, supplied by runoff rain water that filled the cisterns during the wet season.

In this visit we explored 2 cisterns, in order to document the hiding tunnels cut into the cistern in order to provide protection during tight times.

An entrance to one of the Roman period hiding tunnels was explored, as seen in the following photos.

Remains of an ancient village, dated to the Israelite and Byzantine periods. On the site are ruins of a synagogue, fortress and agriculture installations.

A cave, which served for dwelling and also as a hiding place, is adjacent to the synagogue. An opening is seen here on the right side.

The cave was once a natural cave, and later it was expanded to serve as a dwelling place. Inside the cave are walls, which separated the higher human dwelling place to the lower area where the animals were kept.

Ruins of an Iron Age fortress and village, identified as the home town of Jeroboam son of Nebat who split United Monarchy.

Along the wall of the cliff are many natural caves.

The caves were used for shelter, storage places, hiding places, and residential. Ceramics remains collected in the cave are dated to Iron Age and Hellenistic periods, so this hiding place was in use in earlier periods than the Roman period.

Some narrow passages require crawling into tight spaces:

Ancient Iron Age and Hellenistic period city near Beit Guvrin, with an amazing underground lower city.

One of the underground complexes is a columbarium structure, composed of several halls, arranged in the form of a double cross. During the 2nd century AD the cave was changed again into a hiding place, and tunnels were cut into the original structure to make it suitable for a concealed habitation during the Bar Kochba revolt. Such underground hiding places are found in other caves.

Ruins of a second temple period fortified village, west of Gush Etzion.

The entrance to the underground complex is viewed in the next photo. After a corridor of 7m, the tunnel opens up to a large chamber (10m long, 6-10m wide). Inside the underground complex was a fragment of a Ossuary. A narrow path connects to another underground system – probably a hiding complex.

Herod the Great built this monumental fortress and palace in the Judean desert south of Jerusalem, and was buried here. The site was a rebel stronghold during the great revolts against the Romans.

Underground tunnels were prepared by the warriors of the Great War (66-70 AD) and the Bar-Kochba revolt (132-135 AD). They curved a network of tunnels and stairs in parallel to the water supply system that was built by Herod.

The Great war warriors carved a tunnel to access the water system from the top to the reservoirs without being spotted by the Romans who were besieging the fortress. The Bar-Kokhbah warriors used the tunnels to surprise the Roman army, providing additional exits from the hill.

At the bottom of the underground descent are tunnels that were cut by the warriors. They are seen here on the right side of the reservoir.

A closer view of the entrance to some of the tunnels:

Horvat Geres (Kh. Jurish) – Ruins of a second temple period fortified village, west of Zur Hadasah. Identified as the village of Geresa.

On the east side are additional cisterns. The archaeologists identified four Jewish ritual baths (Mikveh) dated to the second temple period. (Report by E. Klein).

In two of the cisterns the archaeologists also unearthed hiding complexes, probably added during the Bar Kochba revolt as common in many of the Judean Jewish villages during those tragic times.

A Hasmonean period fortress located inside the Ayalon park. It was fortified by Bacchides during the Maccabee revolt.

There are also dozens of cisterns between the houses. These were used to collect the rain water off the roofs during the winter time and used as the source of the drinking water. The cisterns had a secondary use at a later date: A network of narrow tunnels connect some of these holes, and were part of the hiding places that were prepared during the Bar Kochba revolt (131-135 AD). In one of these tunnels a number of coins were found dated to the Bar Kochba revolt.

(b) Samaria

Multi-period fortified city, situated on a high hill in the Northern Samaria region, identified as Roman Narbata.

On the summit is one of the cisterns we explored. This one has a larger entrance on the surface. A narrow entrance to a hiding tunnel is located at the bottom of the cistern.

The team explored the plan of the tunnel.

Ruins of a fortified village situated near the Lebonah ascent. Identified as Kfar Lakitia – one of the Roman garrisons at the end of the Bar- Kokhba revolt.

On the south eastern side is an underground hiding complex. It was initially an underground wine cellar, but later was converted to a hiding place.

Entry to the complex was through a round opening, 60 cm wide, which leads to a bell shaped cistern. Narrow openings in that cistern connect to three chambers. The pottery sherds identified in the hiding complex are dated to the end of the 1st century AD, and therefore it is probable that the hiding complex was hewn during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

On the hill are ruins of a village and agriculture installations dated to the first temple and Roman/Byzantine periods. Ancient wine cellars (26 “Gibeon” type pits) were used to store wine during the First Temple period. These were later reused to construct a labyrinth of secret underground hiding places during the Bar-Kokhba revolt.

Between the cisterns are tunnels that interconnect them together. This was used, many years after the cisterns were cut for agriculture purposes, as an underground hiding place during the Bar-Kokhba revolt.

Ruins of a Biblical city. This site may have been Ramathaim Zophim – the home city and place of burial of prophet Samuel.

More than 50 cisterns were found on the site. These rock hewn cisterns are dated to the first temple period, and is believed that they were used to store wine and oil that was produced here.

A large water reservoir, dated to the Biblical period, is located at the foothill of the eastern hill, just below the city wall. On the west side of the reservoir are openings to underground cavities, which have been cut in a later period. Perhaps, used as hiding tunnels during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Ruins of a multi period village, from the Early Bronze to the Ottoman period, on the side of Allon road in Samaria.

Hiding tunnels, connecting several chambers, were identified in Jibeit. According to Z. Ilan and U. Dinur who explored the hiding complexes, they were cut during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

The archaeological survey identified 4 adjacent bell-shaped cisterns that were dated to the Iron Age, and used as an underground winery. The purpose of these cisterns was to store the grape juice in a cold condition of the underground cavity. The top entrance of these cisterns is small, and had a niche that sealed the top side.

Underground wine reservoirs, dated to the Iron Age, are also known from other places in Ephraim and Samaria. Examples include el-Jib (63 winery cisterns), Sheikh Issa (24 cisterns), Kh. Jama’in and Deir Dakleh. Some of these winery cisterns were later converted to water cisterns, columbarium, and in some cases (as here in Jibeit) into hiding places during the great revolt against the Romans.

A karst system cave in central Samaria, used as a refuge place over thousands of years. Archaeological survey dated findings from the Chalcolithic thru the Mamluk periods (5th millennium BC to the early 2nd millennium AD).

(c) Galilee

A mysterious complex of caves above the Kziv stream, in the Upper Galilee area, with a large engraving of a Roman soldier on the surface of the cliff.

The cliff on the south bank, Mt. Ziv, towers 270m above the valley. In this cliff, facing the temple cave, are dozens of small caves that were used as hiding places during the Great Revolt against the Romans (67-70 AD) and perhaps during other periods.

Ruins of a large multi-period village, located on the eastern slopes of Mount Gilboa.

In one of the caves is an inner tunnel, perhaps a hiding complex.

Traces of a Roman period settlement, with agriculture installations, cisterns and hiding complexes. The underground hiding complex includes 7 large cavities (marked ‘A’ thru ‘G’), connected by corridors.

One of the corridors is seen here:

According to the survey, the ceramics found inside the room are typical Roman – end of 3rd century to beginning of the 4th century.

Khirbet Cana is one of the most likely candidates for the site of Jesus’s first miracle, turning water to wine.

On top of the hill, under many of the houses, are dozens of cisterns that are dug into the stone. They were used both as storage areas and water reservoirs. The water factor was critical for life on the hill, due to the difficulty to fetch the water from the creek or from the valley. They stored the water that was collected from the rain, off the rooftops. The cisterns were also used for hiding places, used in the revolts against the Romans (66/67AD, 131/132, 352). Most of them were inter-connected by tunnels as part of an underground complex.

Hukok

Hukok is an ancient Jewish village that is mentioned in the Bible (Joshua 19:34). It was first settled during the Early Bronze period and continued to the Roman and Byzantine periods. The archaeologists unearthed and restored a remarkable floor mosaic.

A vast hiding complex is currently under excavation.

During the Great revolt and Bar Kokhba revolt, the residents converted a water cistern into a refuge complex, interconnecting it by tunnels with other cavities.

On the northern side of the road, on the foothills above the ruins of Nuris, are a number of caves.

According to Yenon Shivtiel who surveyed a large cave complex in Nurit, it was used as a hiding complex during the great revolt against the Romans, and perhaps later during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Etymology:

- Adobe – Spanish for mudbrick

- Adobe – a mixture of earth and straw, made into bricks and dried in the sun

- Mud Brick– In Hebrew: Livnei Botz

Biblical References:

The Bible contains several references to hiding places, which were used by various individuals and groups to escape danger, persecution, or death. Here are some notable biblical references to hiding places:

Old Testament

- David Hiding from Saul

- 1 Samuel 22:1-2: “David left Gath and escaped to the cave of Adullam. When his brothers and his father’s household heard about it, they went down to him there. All those who were in distress or in debt or discontented gathered around him, and he became their commander. About four hundred men were with him.”

- 1 Samuel 24:1-3: “After Saul returned from pursuing the Philistines, he was told, ‘David is in the Desert of En Gedi.’ So Saul took three thousand able young men from all Israel and set out to look for David and his men near the Crags of the Wild Goats. He came to the sheep pens along the way; a cave was there, and Saul went in to relieve himself. David and his men were far back in the cave.”

- The Israelites Hiding from the Midianites

- Judges 6:2: “Because the power of Midian was so oppressive, the Israelites prepared shelters for themselves in mountain clefts, caves and strongholds.”

- Elijah Hiding from Jezebel

- 1 Kings 19:3-9: “Elijah was afraid and ran for his life. When he came to Beersheba in Judah, he left his servant there, while he himself went a day’s journey into the wilderness. He came to a broom bush, sat down under it and prayed that he might die. ‘I have had enough, Lord,’ he said. ‘Take my life; I am no better than my ancestors.’ Then he lay down under the bush and fell asleep. All at once an angel touched him and said, ‘Get up and eat.’ He looked around, and there by his head was some bread baked over hot coals, and a jar of water. He ate and drank and then lay down again. The angel of the Lord came back a second time and touched him and said, ‘Get up and eat, for the journey is too much for you.’ So he got up and ate and drank. Strengthened by that food, he traveled forty days and forty nights until he reached Horeb, the mountain of God. There he went into a cave and spent the night.”

- Lot Hiding in Zoar

- Genesis 19:17-22: “As soon as they had brought them out, one of them said, ‘Flee for your lives! Don’t look back, and don’t stop anywhere in the plain! Flee to the mountains or you will be swept away!’ But Lot said to them, ‘No, my lords, please! Your servant has found favor in your eyes, and you have shown great kindness to me in sparing my life. But I can’t flee to the mountains; this disaster will overtake me, and I’ll die. Look, here is a town near enough to run to, and it is small. Let me flee to it—it is very small, isn’t it? Then my life will be spared.’ He said to him, ‘Very well, I will grant this request too; I will not overthrow the town you speak of. But flee there quickly, because I cannot do anything until you reach it.’ (That is why the town was called Zoar.)”

- Obadiah Hiding Prophets

- 1 Kings 18:4: “While Jezebel was killing off the Lord’s prophets, Obadiah had taken a hundred prophets and hidden them in two caves, fifty in each, and had supplied them with food and water.”

New Testament

- Jesus Avoiding Arrest

- John 8:59: “At this, they picked up stones to stone him, but Jesus hid himself, slipping away from the temple grounds.”

- John 10:39-40: “Again they tried to seize him, but he escaped their grasp. Then Jesus went back across the Jordan to the place where John had been baptizing in the early days. There he stayed.”

- Paul Hiding

- Acts 9:23-25: “After many days had gone by, there was a conspiracy among the Jews to kill him, but Saul learned of their plan. Day and night they kept close watch on the city gates in order to kill him. But his followers took him by night and lowered him in a basket through an opening in the wall.”

General Themes

- God as a Refuge

- Psalm 27:5: “For in the day of trouble he will keep me safe in his dwelling; he will hide me in the shelter of his sacred tent and set me high upon a rock.”

- Psalm 32:7: “You are my hiding place; you will protect me from trouble and surround me with songs of deliverance.”

- Prophetic and Eschatological Writings

- Isaiah 2:19: “People will flee to caves in the rocks and to holes in the ground from the fearful presence of the Lord and the splendor of his majesty, when he rises to shake the earth.”

In summary, the Bible frequently mentions hiding places, whether for physical safety, spiritual refuge, or divine protection. These references span both the Old and New Testaments, illustrating a common theme of seeking and finding safety in times of danger.

Links:

- Rock-Cut Hiding Complexes from the Roman Period in Israel Boaz Zissu and Amos Kloner (2009)

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- Boaz Zissu academic papers

- Vast underground hiding complex found in Hukok – JNS, Mar 18, 2024

- Galilee refuge caves Malham (Hebrew); Article by Asher Ovadiah and Yinon Shivtiel

- Hiding Complexes in the Galilee, Israel: Artificial Refuge

Caves in the Early Roman Period – Yinon Shivtiel, Hypogea 2017, pp 85-94

BibleWalks.com – walk with us through the sites of the Holy Land

Miqveh installations<<<—Previous —<<< All Info >>>—Next Info—>>> Mud Bricks

This page was last updated on Nov 24, 2024 (add article, nurit)

Sponsored links: