Tel Shalem (Tell Salim, Tell er Radghah) is an ancient mound, located in the Jordan valley near a bountiful spring.

Home > Sites > Jordan Valley> Tel Shalem (Tell Salim, Tell er Radghah, Tell er Ridhghah)

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Mound

* Mound Pottery

* Roman Camp

* Aenon near Salim

* Spring Pottery

* Flight Over

Links

Etymology

Background:

Tel Shalem (Tell Salim, Tell er Ridhghah) is an ancient mound, located in the Jordan valley, 11km south of Beit Shean (Scythopolis). Major ancient roads intersected near the Tell, including a Jordan river crossing route. The elliptical mound, covering an area of 80 x 100m, was populated from the Early Bronze through the Mameluke periods. In modern times it was used by the military to protect the border.

To its south west was a large Roman military camp, constructed during the Bar Kochba revolt.

On the north west of the mound are remains of a large Early Bronze I fortified city, covering 40 dunams but buried under alluvial soil.

On its north side is the spring named Ein Avraham, known in the New testament as Aenon where John the Baptist was baptizing people (John 3, 23): “Now John also was baptizing at Aenon near Salim, because there was plenty of water, and people were coming and being baptized”.

Map / Aerial View:

The aerial map below shows the area around Tel Shalem, indicating the main points of interest. The mound height is -212m (below sea level), towering about 5m over the the area.

Tel Shalem is 2km south of Kibbutz Tirat Zvi. Access is via road #6678 to Kibbutz Tirat Zvi, and then along the fish ponds. The Kibbutz is closed on Shabbats, so an alternative way is from Horvat Menorah then along a dirt road bypassing the Kibbutz.

History:

- Epi-Paleolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods

Above the north bank of the Ein Avraham stream is a ruin named Horvat Al’al (Tell el ‘Alya, meaning the ‘tall mound’ ). Along the stream are heaps with remains of a settlement of these prehistoric periods. There are traces of structures, flint stones and ceramics.

- Bronze and Iron (Biblical) Age

Tel Shalem (Tell er Ridhghah) was a major settlement in this area, established during the Early Bronze period and continued to the Middle ages. The nearby settlement of Tel Malqet (Tell Molikat) was another Middle Bronze II period city.

According to N. Zori (1962) and A. Cohen (2010), the ceramics dated on Tel Shalem and its vicinity were dated in these periods to the Early Bronze, Middle Bronze II, Late Bronze, Iron Age I and Iron Age II.

The cities and roads during the ancient periods, up to the Roman period, are indicated on the Biblical Map below. The site is on the path of a major south/north ancient road along the Jordan valley, depicted here as a grey dashed line (Dorsey’s Bronze/Iron age route ‘A3’). It is not far from the Jordan river, as illustrated as a blue line, where a river crossing crossed the ford to the eastern side of the river.

Map of the area of Beit Shean valley – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

River Crossing route:

During the antiquity the Jordan river crossings was by crossing fords along the river rather than using bridges or ferries. Bridges were constructed only during the Roman and Mameluke periods. Dorsey (“The roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”) claims that no Bronze or Iron Age bridges were found along the Jordan, and the Bible does not mention such bridges. Tel Shalem was founded as a city along the ancient routes that crossed the river towards the east.

David Dorsey (“The roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”, 2018, pp. 104, 114) described a Bronze/Iron age road that connected Rechov, the major city during that time, through a number of Bronze/Iron age sites along these routes. The road reached a major river crossing near Tel Abu Sus (4km south east of Shalem):

- T9b – from Rehov to Tel Abu Sus (sites #272 thru 277) – This road connected Rehov, the most important city in the area, through the following sites:

- Tellul eth Thaum – Tel Teomim (#272)

- Sde Terumot site (#273)

- Tel ‘Alya – adjacent to Tel Shalem on the north side (#274)

- Tell er Ridhghah (Tel Shalem) (#275)

- Tell Molikat (#276)

- Kh. Khisas ed Deir (#277)

- to the river crossings near Tell Abu Sus.

From the river crossings near Abu Sus, the way along Wadi Yabis would lead to Jabesh Gilead. This is the Biblical Yabesh of Gilead where the Prophet Elijah was born in the 9th century.

Another route from Samaria hills used a west-east route along Bezeq valley connecting to Rehov and to the river crossing. It is seen as a dashed line towards the left (west) side. Tel Shalem is near the south banks of Bezeq stream.

Destruction:

The city on Tel Shalem, as well as other cities in the Beit Shean area, was destroyed in the Assyrian conquest. In 732 BC was an intrusion to the North of Israel by the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III, who annexed the area (as per 2 Kings 15: 29):

“In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took … Galilee…and carried them captive to Assyria”.

According to the ceramics survey, the mound was partially resettled during the Persian period. However, major activity near the mound resumed only following the Roman period.

- Early Roman period – “Aenon near Salim”

On north side of Tel Shalem is the spring named Ein Avraham – a modern name commemorating a fallen soldier. This spring and its pool are likely to be known as the New testament place called “Aenon near Salim”. This is where John the Baptist was baptizing people after baptizing Jesus in Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan (John 3, 23):

“Now John also was baptizing at Aenon near Salim, because there was plenty of water, and people were coming and being baptized”.

Aenon is the Hellenized form of the term for ‘spring’, similar to Hebrew (עין) and Arabic (‘Ain).

John baptizes Jesus in Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan

(Painting at St. John BaHarim, Ein Kerem)

The identification of “Aenon near Salim” remains uncertain. The location of Aenon is suggested by the description that “there was plenty of water there” (John 3:23) and its position on the west side of the Jordan River. The name “Salim” may have preserved the Hebrew word “Shalem.” .

Eusebius of Caesarea, a 4th-century Greek historian of the Church, offered identifications of Biblical places in the Holy Land in his book Onomasticon. In this book he proposed that “Aenon near Salim” was located at “a village in the (Jordan) valley, at the eighth milestone from Scythopolis, … called Salumias.”. The reference to Salumias in Eusebius’ work indicates that this village was known during the late Roman period and was part of the wider network of Roman settlements in the region. The 8th milestone fits the distance from Beit Shean/Scythopolis to Tel Shalem (8 Roman miles is 12km).

Although direct archaeological evidence specifically identifying Salumias at Tel Shalem is limited, the discovery of Roman-era artifacts, such as the statue of Hadrian and remnants of Roman fortifications, suggests that the area was indeed inhabited and significant during the Roman period. This evidence provides a reasonable basis for associating Tel Shalem with the location of John’s baptizing place.

Note that there are other candidates for the place of Aenon. There are many springs in the vicinity of Tel Shalem. One of them is a spring 1.5km south of Tel Shalem, named ‘Ain ed-Dir (“the spring of the monastery”).

![]() Read more on this subject in our page on Aenon near Salim.

Read more on this subject in our page on Aenon near Salim.

-

Roman and Byzantine period

Roman camp:

Tel Shalem was likely a Roman military settlement, as the site includes remains of a Roman fort, among other structures. The fort was part of the Roman Empire’s defensive network in the region, and the statue of Hadrian might have been part of a larger monument or temple dedicated to the emperor. The site provides important insights into the Roman presence in the region during the 2nd century CE, offering valuable archaeological and historical information about the Roman military, their settlements, and their interactions with the local population.

The excavations were made to determine the boundaries of the camp, which was estimated to measure approximately 180m x210m. Three settlement layers were identified: the upper layer contained sparse remains from the Mamluk period. Beneath it, a layer was discovered that included several graves without indicative finds, possibly from the same period. The third and main layer represents the Roman settlement and camp. According to an inscription found in the camp, the camp was occupied by a detachment of the Sixth Roman Legion (Legio VI Ferrata). That Legion was incorporated into the Roman army in 30BC and moved in 69 AD to Judea to fight the great revolt. Following the Bar Kochba revolt, the Legion moved in 138 AD to the Roman camp Legio near Megiddo until they were dismantled at the end of the 4th century.

The camp was likely established at the end of the first century or the beginning of the second century AD. Ceramic and numismatic evidence suggests that the camp was abandoned and no longer in use soon after the mid-second century. The structures that were uncovered were built of mud bricks laid on stone foundations. On the southern border of the camp, a bathhouse was partially exposed, featuring impressive mosaic floors with geometric patterns.

Extensive excavations are in progress inside the Roman camp on the south side of Tel Shalem.

Hadrian statue:

This site is significant primarily for the discovery of a well-preserved bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, which dates back to the 2nd century CE. The statue was found in 1975 and is notable for its detailed craftsmanship, reflecting the high level of artistry of the period. The statue depicts Hadrian in military attire, wearing a highly detailed cuirass (breastplate) adorned with mythological scenes. This representation underscores Hadrian’s role as both a military leader and a divine figure in Roman imperial culture. Hadrian’s presence in this region is linked to his efforts to suppress the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 AD), a major Jewish uprising against Roman rule. The statue might have been part of a monument or temple dedicated to the emperor, reflecting the Roman practice of imperial worship.

Most of the fragments of the Hadrian statue, about 50 in number, were found at a depth of 30 to 80 cm in a brick structure that was only partially uncovered in the northern part of the camp. Additional fragments were collected from the site even after the excavations in the camp area. It should be noted that the camp area had been cleared and plowed to a depth of 2.10 meters in previous years, and it is almost miraculous that the parts found during and after the excavations survived. In 1984, workers from the conservation laboratory at the Israel Museum succeeded in reconstructing the upper part of the statue, identifying it as either an emperor standing in armor, addressing his troops in an adlocutio gesture, or as a ruler standing with a scepter in one hand and holding a sword in the other. This type of statue, slightly larger than life-size and made of bronze, likely represented the emperor in the Roman legion during all his travels and was placed in his camps in a temple adjacent to the headquarters. It is possible that the site of the discovery should be identified as a sacellum (a small shrine).

- The Monumental Inscription

In late January and early February 1977, during the excavation of foundations for a tool shed about 1.5km northwest of the camp at Tel Shalem, two stone sarcophagi made of hewn stones were uncovered, and a third grave was partially exposed. The site of the discovery is locally known as “Giv’at Hilboni”. Each grave contained around 15 burials dated to the 4th-5th century AD.

When one of the graves was opened, it was revealed that some of the hewn stones used in its construction were fragments of slabs bearing remnants of a monumental Latin inscription. Six slabs or parts of them survived and were reassembled. They represent about a quarter of the inscription’s estimated full length. The inscription contains three lines engraved with exceptional quality, with exceptional large letters (41 cm) that are unprecedented in the East. The inscription is approximately 11 meters wide and 1.30 meters high, and its text, after restoration and completion by Werner Eck and Gideon Foerster, is as follows:

(1) IMP(ERATORI) CAE[S(ARI) DIVI T]RA[IANI PAR-]

(2) TH[I]CI F(ILIO) D[IVI NERVAE NEP(OTI) TR]AIANO [HADRIANO AUG(USTO)]

(3) PON[T]IF(I) M[AX(IMO), TRIB(UNICIA POT(ESTATE) XX?, IMP(ERATORI) I]I, CO(N)S(ULI) [III, P(ATRI) P(ATRIAE) S(ENATUS) P(OPULUS) Q(UE) R(OMANUS)?]

The dimensions and wording of the inscription indicate that it was placed on the front of a triumphal arch dedicated to Hadrian. The proximity to the site where the bronze statue of the emperor was found suggests, cautiously, that the statue might have stood atop this arch.

Who initiated the construction of the arch? When was it erected, and for what event? The two most plausible events that could have led to the erection of such a monument are Hadrian’s visit to the area in 130 AD or, more likely, the conclusion of the difficult war against the Bar Kochba revolt the Senate’s declaration of Hadrian’s victory in 136 AD.

The fact that the inscription is in Latin, rather than Greek, the common language in the East, supports the assumption that the dedication of the inscription and the construction of the arch were the result of an initiative by the central authorities and a decision of the Senate and the Roman people, or alternatively, by the legion’s command.

Roman Roads:

A major Roman road passed on the west side of the site. It connected Beit Shean/Nysa-Scythopolis to Jericho and Neapolis (Shechem). Another road from Pella (on the east side of the river) to Niapolis (Shechem) intersected with the road near the tell.

In 1952 a Roman milestone was found in nearby Kibbutz Sde Eliyahu (4km north of Shalem). It dates to 213 AD, during the reign of emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (aka Caracalla), 198-217 AD. The milestone stood on the 5th Roman mile (7.4 km) from Beit Shean to Schechem. It is seen here on the left side. A number of milestones are on display in Tirat Zvi, from the 7th Roman mile north of Tel Shalem, are seen on the right. They were reported by Zori (1962, p. 182, site 118) and moved to the open museum in 2024.

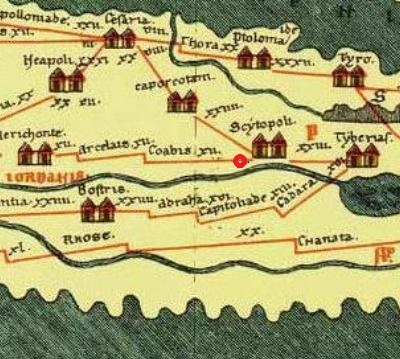

A section of the Peutinger map (Peutingeriana tabula), based on a 4th century map of Imperial Roman roads, is here below. It is oriented with the top side as the west. The map shows the major military roads between Jericho (on the middle left, named here by its Roman name – “Herichonte”) to Beit Shean (“Scytopoli”). The distances are marked with Latin numbers. The site is marked along this road as a red circle.

Section of the 4th Century Peutinger Map, focusing on the Jericho-Beit Shean-Tiberias road

- Early Arab period

Tell Shalem is named in Arabic “Tell er Ridghah” – The mound of the mud. This name was given due to the event of the battle between the Byzantines and the Muslim Arab forces in 634 CE, when the reservoirs were opened to flood the valley with mud as a desperate defensive tactic by the Byzantines to slow down or stop the advancing Arab forces. Flooding the area would have created a difficult, muddy terrain, potentially hampering the movement of troops and horses.

- Crusaders/Mamelukes

According to the ceramic survey, the village continued to be settled in this period.

The village’s economy was centered around farming and the sugar industry. Archaeological evidence reveals that sugarcane was cultivated and processed along both banks of the Jordan Valley. The area offered ideal conditions for sugarcane cultivation, including a tropical climate, abundant flowing water, and soil rich in minerals. Ceramic parts used in this industry, and dated to the Mameluke period, were found in the area of the Roman camp and west of it.

Sugarcane cultivation spread through the Middle East during the Islamic period, likely introduced from Southeast Asia. By the 12th and 13th centuries, the sugar industry was well-established in the Jordan Valley and other parts of the Levant. Sugar was a highly valued commodity, both locally and for export. It was used not only as a sweetener but also in medicine and as a preservative. The production and trade of sugar became a major economic activity, contributing to the wealth of the region.

- Cultivation: The Jordan Valley’s tropical climate, combined with its fertile, mineral-rich soils and abundant water supply from the Jordan River and surrounding springs, made it an ideal location for sugarcane cultivation. The warm temperatures and long growing season allowed for multiple harvests per year.

- Refinement: After harvesting, sugarcane was processed locally in sugar mills. These mills typically consisted of crushers that extracted the juice from the cane, which was then boiled down to produce crystallized sugar. Archaeological remains of sugar mills, along with tools and equipment related to sugar production, have been found in the region, indicating a well-developed industry. For example, remains of a Crusaders period sugar cane factory was found on the west side of the spring at Tel Saharon.

- Infrastructure: The sugarcane industry required significant infrastructure, including irrigation systems to ensure a consistent water supply, and roads or waterways for transporting the final product. Some remains of these infrastructures, such as aqueducts and millstones, have been uncovered through archaeological excavations.

-

Ottoman period

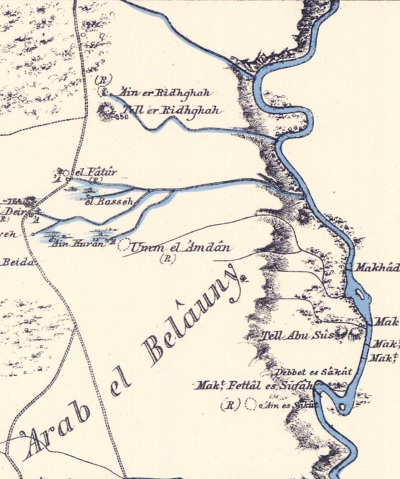

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their map is seen here. The map is part of sheet 12 of their survey results. They wrote about Tel Shalem (Volume 2, p. 247):

“Tell er Ridhghah —A low mound, apparently artificial. On the north a good spring and a few ruined houses, with the little ruined

dome of Sheikh Salim”.

Part of Map sheet 12 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Notice in the map that near the site are several river crossings, with a “Makt” prefix. These crossings were on foot at convenient points where the flow of the Jordan river slowed down and allowed walking on the river bed. The map also shows a double-dashed road that passed west of the mound, marked as a Roman road. Its route follows the same route as the modern road #90 south towards Jericho.

-

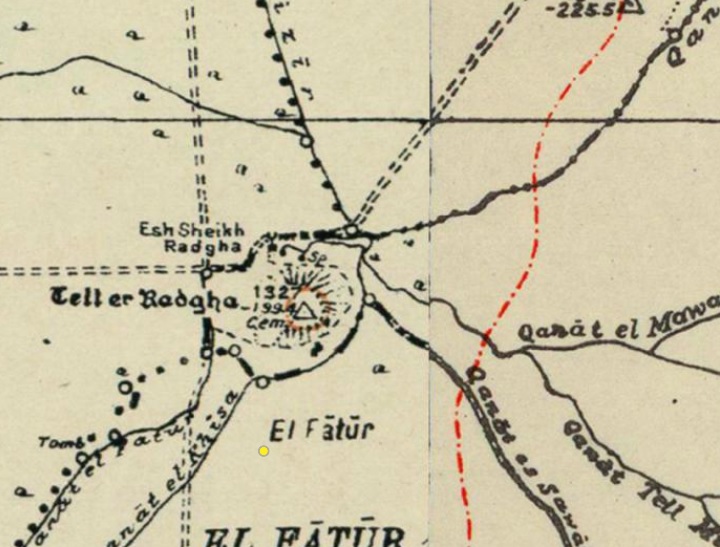

British Mandate

The site was named in the British period maps as “Tell er Radgha”. A cemetery appears on the mound, probably tombs of bedouines. A sheikh’s tomb (Esh Sheikh Radgha) appears on the north west. A spring (marked as SP) appears on the north side. Several aqueducts (“qanat”) convey the spring’s waters to the fields around it. A farming Arab village, el Fatur, existed south of the site at that time.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

The renowned Biblical archaeologist W.F. Albright visited the site in 1925 and described it as a low hill.

An old photo (c 1948) shows the spring of Shalem prior to the construction of the fish pond. Tel Shalem is seen in the background.

Photo courtesy Sturman museum, A. Keidar

- Modern Period

On June 1948 an IDF soldier, Avraham Haber, was killed by a Jordanian sniper on Tel Shalem. The spring was named after him – Ein Avraham.

The army dug extensive fortifications on the mound, especially on the south eastern foothills. The military works caused considerable damage to the mound.

Kibbutz Tirat Zvi constructed fish pools in the area, utilizing the abundant waters.

Photos:

(a) The Mound

Tel Shalem is a low elliptical mound, built on the south bank of the stream flowing from Ein Avraham spring. It was damaged by military works as part of the defenses along the Jordan river. This view is from the Roman camp on the south west side of the hill.

The mound is built of two hills with a ridge between them. The east side, seen here from the north, was the upper city (acropolis). It was damaged by heavy military works. The western side is the lower city.

A steep ascent is required to get to the top of the mound, 15m above the area. On the summit is an observation place where you can sit and enjoy the views.

Earthworks and trenches damaged the ancient mound. The following view is from the top of the mound towards the south west. In the background are the eastern Samarian hills of southern Mt. Gilboa.

(b) Pottery found on the mound

According to N. Zori (1962) and A. Cohen (2010), the ceramics dated on Tel Shalem and vicinity are: Early Bronze, Middle Bronze II, Late Bronze or Iron Age I, Iron Age II, Persian, Hellenistic, Early Arab, Roman, Byzantine, Early Arab, Crusaders and Mameluke (Many). In the area of the Roman camp and the spring below the mound, the pottery fragments were dated to the Roman and Byzantine period.

We looked around the foothills for pottery fragments that could date the occupation on Tel Shalem. All findings were left on site.

We found the following fragments and dated them:

(c) Roman camp

Extensive excavations are conducted in the area of the Roman camp, south west of the mound. The camp served the Legio VI Ferrata from the end of the 1st century AD to the middle of the 2nd century.

Three settlement layers were identified: the upper layer contained sparse remains from the Mamluk period. Beneath it, a layer was discovered that included several graves, possibly from the same period.

The third and main layer represents the Roman settlement and camp. All ceramics were dated to the late Roman period (2nd century AD).

(d) “Aenon near Salim”

On north side of Tel Shalem is Ein Avraham spring- a modern name of the spring commemorating a fallen soldier. Its Arabic name is ‘Ain er Ridhghah (name after the mound). The waters of the spring flow eastwards and fill up the pool.

This view from the top of the mound towards the spring and its adjacent pool. A concrete structure, housing a pumping station, is seen here on the left side.

The spring and its pool are likely to be known as the New Testament place called “Aenon near Salim”. This is where John the Baptist was baptizing people after baptizing Jesus in Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan (John 3, 23): “Now John also was baptizing at Aenon near Salim, because there was plenty of water, and people were coming and being baptized”.

![]() Read more on this subject in our page on Aenon near Salim.

Read more on this subject in our page on Aenon near Salim.

(e) Flight Over

![]() Fly around the site with this YouTube video.

Fly around the site with this YouTube video.

Video captured on Aug 2024

Links:

* External links:

- N. Tzori 1962 – Tel Shalem – site 62

- A. Cohen Tavor (Rehob area survey, 2010): Tel Shalem – sites 102 (Tel Shalem), 103 (Shalem north), 104 (Roman camp), 105 (H. ‘Al’a)

- Sugar in the Kingdom of Jerusalem – A Crusader Industry between East and West”; [Anat Peled, IAA]

- The Sugarcane Industry in Jericho, Jordan Valley – Hamdan Taha, 2015

- Tel Shalem Hadrian reconsidered R. A. Gergel, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 95, No. 2 (Apr 91), pp. 231-251 (21 pages)

- “The Manasse hill country survey” Volume 4 [Adam Zertal , 2005]

- Site 23 – ‘Ain ed-Deir (pp. 154-156)

- Site 18 – Tel Shalem (pp 144-147)

- Site 17 – Shalem Roman camp (pp 142-143)

* Internal links:

- Aqueducts – information page

- Roman roads – info page

- Mosaic floors – info page

- Sugar history

- Aenon near Salim – search for John the Baptist place of Baptizing

- YouTube – BibleWalks’ aerial views

Etymology – behind the name:

- Tell er Radgha, Tell er Ridhghah, Tell Ridgha – Arabic: “The mound of the mud”. This name was given due to the event of the battle between the Byzantines and the Muslim Arab forces in 634 CE, when the reservoirs were opened to flood the valley with mud as a desperate defensive tactic by the Byzantines to slow down or stop the advancing Arab forces. Flooding the area would have created a difficult, muddy terrain, potentially hampering the movement of troops and horses.

- Tel Shalem – the Hebrew name.

- Sheikh es Selim – a ruined Sheikh’s tomb on the north west side of the mound, an Arab name that preserved the ancient name.

- Salumias – the Roman village located at Tel Shalem (according to Eusbesius)

BibleWalks.com – walks along the Jordan river

Horvat Baat<<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Jordan Valley site—>>>Aenon Near Salim

This page was last updated on Sep 3, 2024 (move Aenon to new page)

Sponsored Links: