Tel Ashkelon is an important ancient port city, with 4,000 years of history.

Home > Sites > Shefela > Tel Ashkelon (Ascalon)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial Views

* Canaanite fortifications

* Canaanite Gate

* Harbour

* North walls

* West

* South West

* Center

* Basilica

* Apsidal Building

* Wells

* East walls

* Mary Viridis

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Ashkelon encompasses a history of 4,000 years, a port city located on the main trade route from Egypt to the North. It started as a huge fortified Canaanite city, continued as a Philistine city, turning into a thriving commercial center and independent city during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, then ending as a Crusader border fortress.

Zecharia (9:5): “Ashkelon shall see it, and fear…”.

Location and Map:

Ruins of ancient Ashkelon are located in the Ashkelon National park, southwest of the modern city. The site is situated on a sandstone (Kurkar) ridge, along the sandy beach.

The entrance and exit are through a gate in the northern side. Self guided tours cover various sections of this large park. An overnight campground exists in the center of the park.

History:

-

Bronze period – a major Canaanite city

Establishment – 20th century BC: The Canaanite city was established in ~1950 BC, having a population of 15,000. The large city (600 Dunam – 60 Hectares), with a length of 1100 meters and width of 600 meters, covering the entire sandstone ridge which is the current size of the national park. The city was protected by 15m (50 ft) high ramparts, a deep moat, with a total length 2200 m (1.25 miles). The ramparts were based on earth which was moved into position, then covered with a glacis – an outer face of field stones sealed with a smooth layer of clay. These steep slippery slopes made the ascent difficult for the assailants, kept them in an open area for the archers, while also strengthening the walls against undermining. The northern city gate, the oldest arched gate in the World, was unearthed inside the ramparts and reconstructed. The water supply of the city was based on an underground water supply which was extracted via wells.

Enemy Curse tablets – 19th century BC: References to the Canaanite city were found in several Egyptian sources, starting in the 19th century Egyptian (12th Dynasty) enemy-curse clay tablets as “Ascona”.

Egyptian conquest – 1468 BC: The Egyptians conquered Canaan following the battle of Megiddo. Their control of Canaan lasted for 350 years, and Ashkelon was a major station along the only road connecting Egypt to Canaan.

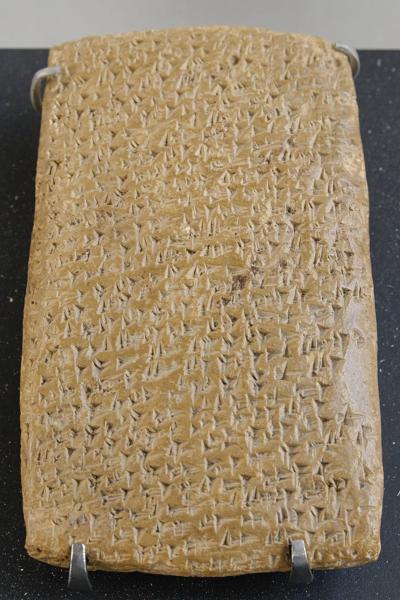

Amarna Letters – 14th century BC: Ashkelon was an important city in this period: It was mentioned in seven Tell el-Amarna letters .

This 14th century BC Egyptian archive of clay tablets has letters from the king of the city, which addresses the Egyptian Pharaoh.

One of the letters is from the Governor of the city, named Yitia, who writes to Pharaoh about his supply of goods to the Egyptian Army, and his payment of taxes to Egypt. In another letter, Abdi-Khiba – the governor of Jerusalem – warns against the Habirua people (perhaps the Hebrews?) who are the enemies of Egypt and are invading the Land, and warns that some of the Canaanite cities (including Ashkelon) are assisting them:

“The Habiru have devastated all the territory of the king…. Behold, the territory of Gazri, the territory of Ashkelon, and the city of La[chish], have given them oil, food, and all their necessaries. Let the king therefore care for the troops ! Let him send troops against the people who have committed a crime against the king, my lord!”.

One of the Tell Amarna letters (Louvre Museum, Public domain CC 2.5)

Cuneiform writing on a clay tablet.

Seti I and Ramses II – 13th century BC: The Hittite empire, centered in Anatolia, Turkey, reached its height during the mid 14th Century, and expanded to the south. The Hittites conquered Syria and influenced the Canaanite cities to revolt against the Egyptians. Therefore, the Egyptians confronted the Hittites in order to secure their grasp of Canaan. During the first intrusion by Pharaoh Seti I through Canaan (1301 BC), the Egyptians reached Beit Shean and north to the port city of Ulaza.

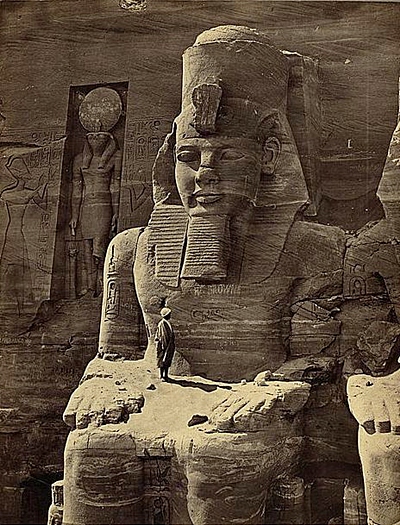

His son, Ramses II (reign 1279-1213) – a Pharaoh identified with the Exodus – continued the Egyptian intrusions into Canaan in order to keep the Canaanites under control. Ashkelon revolted against Egypt, so Ramses placed a siege and conquered it, as illustrated on a palace in Upper Egypt.

Statue of Ramses II at Abu Simbal [Photos LOC)

In the 5th year of Ramses II (1274), the Egyptians fought against the Hittites in Kedesh (Syria), with severe casualties to both sides. It took the two empires 16 more years of clashes, and in 1258 a peace treaty was sealed. The ceramic tablet of the treaty, the oldest known parity treaty in the World, is seen here:

Kedesh treaty – 1286 BC (Istanbul Archaeology Museum)

His son Merneptah (1213-1203) made another campaign to Canaan in 1208. In the famous stele the name “Israel” appears for the first time (“Israel is wasted…its seed is no more.”).

Merneptah’s Israel stele in Egyptian Museum

in Cairo (Wescribe; license CC3.0)

But the reality was that the Israelites became during his time to the most powerful group in Canaan, after returning from the exile in Egypt and conquering the Canaanite cities. Thus ended the Egyptian presence in Canaan.

The Biblical map below shows the location of Ashkelon and the major cities during the ancient times. The port city is marked with a red circle near the Mediterranean sea. The coastal road (Via Maris, Way of the Sea), a major caravan route connecting the south to the north, passed near the city. Another road going westward connected it to the heart of the land.

Ashkelon and the south west of Israel – during the Biblical periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

Conquest by Joshua: The Canaanite city of Ashkelon was conquered by the people of Judah (Judges 1:18): “Also Judah took Gaza with the coast thereof, and Askelon with the coast thereof, and Ekron with the coast thereof”.

-

Iron (Biblical) age I – Invasion of “Sea people”

The Philistines: The “Sea Peoples” from the Aegean sea landed in Canaan and Egypt in waves of invasions during the 12th century BC. They eventually settled along the eastern shores of the Levant, in a region called “Pleshet”, named after the Philistines (Hebrew: Plishtim). They eventually became the arch enemies during the period of the Judges (12th-10th century) and the Israelite Kingdom (10th – 6th century).

The identity of the invaders is not certain, and several hypotheses attempt to resolve the origins of these people:

-

The Bible: wrote about the Philistine invasion (Amos 9 7): “Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor…”. Caphtor is the island of Cypress. Another Biblical source points out to the source of the Philistines (Jeremiah 47 4): “Because of the day that cometh to spoil all the Philistines, and to cut off from Tyrus and Zidon every helper that remaineth: for the LORD will spoil the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor”.

-

Egyptian sources: Ramses III confronted the Sea People invaders in 1168BC, in the sea and on land. A relief describing the naval battle, located in Medinet Habu (Tebes, Upper Egypt), tells about the invasion: “The foreigners made a conspiracy in their island…their confederation ware Plst, Skl, … no land could stand before them…they were coming towards Egypt, and fire walked before them.” The “Skl” may have been, according to some scholars, Sikels from Sicily.

Following the battles, the Egyptians managed to repulse them into a small enclave in the southern coastal cities of Canaan (from Gaza to Ashkelon), as per (Joshua 13, 3): “…five lords of the Philistines; the Gazathites, and the Ashdothites, the Eshkalonites, the Gittites, and the Ekronites”.

After the Philistines conquered Ashkelon, they rebuilt a smaller city and fortified it. It was their only port city, and therefore important for their links to the Mediterranean commerce.

The Israelite cities on the low hills along the coast were affected by the push of the Philistines eastwards into the land of Judah.

Their conflict with the Israelites started in the mid 11th century BC, and one of the stories associated with this conflict is the heroism of the mighty Samson of the tribe of Dan, who was born in the village of Zorah (3km north of Beit Shemesh) and was a Judge for 20 years.

Samson attacked a group of people in Ashkelon, after his first Philistine wife (of Timnath) betrayed him by disclosing his riddle to her relatives (Judges 14: 19):

“And the Spirit of the LORD came upon him, and he went down to Ashkelon, and slew thirty men of them, and took their spoil, and gave change of garments unto them which expounded the riddle. And his anger was kindled, and he went up to his father’s house”.

Samson slaying the Lion – – Drawing by Gustav Dore

As per Judges 14: 8-9

The Philistines continued to struggle with the Israelites, and managed to defeat Israel in the battle of Eben Ezer.

The great battle of Eben-Ezer occurred in the middle of the 11th C between Ebenezer and Aphek, at about 1050 BC. This battle is fully detailed in the Bible (1 Samuel 4 1): “Now Israel went out against the Philistines to battle, and pitched beside Ebenezer: and the Philistines pitched in Aphek”.

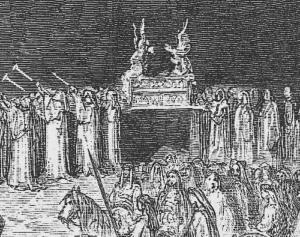

The Bible describes the course of the battle, and its tragic results: 34,000 Israelite soldiers dead, the two spiritual leaders (sons of Eli) were killed, and worse: the Ark of Covenant, which was brought from Shiloh to encourage the army, was taken by the Philistines (1 Samuel 5 1): “And the Philistines took the ark of God, and brought it from Ebenezer unto Ashdod”.

Ark of Covenant moved to the battlefield – Part of a drawing by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

This defeat caused a shock to Israel, and brought the people to demand a strong monarch leadership rather than the existing administration by judges.

-

Israelite Kingdom (10th -6th century B.C.)

King Saul, the first anointed King of Israel (~1025-1006 BC), managed to push the Philistines back to their cities after Saul’s victory over the Philistines. They retreated from the hills of Samaria and Judea (1 Samuel 14 31): “And they smote the Philistines that day from Michmash to Aijalon”. The constant friction with the Philistines is also underlined in the battle between David and Goliath in the Valley of Elah.

Saul later died in the battle of Mt Gilboa (1 Samuel 29 1, 31 1):

“Now the Philistines gathered together all their armies to Aphek… Now the Philistines fought against Israel: and the men of Israel fled from before the Philistines, and fell down slain in mount Gilboa.”

David, who succeeded Saul as King of Israel, mourned this tragic end (2 Samuel 1 19-20):

“The beauty of Israel is slain upon thy high places: how are the mighty fallen! Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askelon; lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice, lest the daughters of the uncircumcised triumph”.

King Saul dies in the battle of Gilboa; drawing by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

Later, King David defeated the Philistines twice, pushing them back to the cities (2 Samuel 5 25): “And David did so, as the LORD had commanded him; and smote the Philistines from Geba until thou come to Gazer”.

The area of Pleshet – the region of the Philistines in the Shefela lowland – was not conquered by the Israelite Kingdom, except for brief occasions. King Uziah managed to conquer parts of Pleshet in the middle of the 8th Century (2 Chronicles 26: 1, 7):

“Then all the people of Judah took Uzziah… and he went forth and warred against the Philistines, and brake down the wall of Gath, and the wall of Jabneh, and the wall of Ashdod, and built cities about Ashdod, and among the Philistines. And God helped him against the Philistines…”.

The conflict with the Philistines is echoed in the words of the prophet regarding the fate of Ashkelon (in bold) as well as the other cities of the Philistines:

-

Jeremiah (47:5-7): “Baldness is come upon Gaza; Ashkelon is cut off with the remnant of their valley: how long wilt thou cut thyself? O thou sword of the LORD, how long will it be ere thou be quiet? put up thyself into thy scabbard, rest, and be still. How can it be quiet, seeing the LORD hath given it a charge against Ashkelon, and against the sea shore? there hath he appointed it”.

-

Amos (1:8): “And I will cut off the inhabitant from Ashdod, and him that holdeth the sceptre from Ashkelon, and I will turn mine hand against Ekron: and the remnant of the Philistines shall perish, saith the Lord GOD”.

-

Zephaniah (2:4-7) :”For Gaza shall be forsaken, and Ashkelon a desolation: they shall drive out Ashdod at the noon day, and Ekron shall be rooted up. Woe unto the inhabitants of the sea coast, the nation of the Cherethites! the word of the LORD is against you; O Canaan, the land of the Philistines, I will even destroy thee, that there shall be no inhabitant. And the sea coast shall be dwellings and cottages for shepherds, and folds for flocks. And the coast shall be for the remnant of the house of Judah; they shall feed thereupon: in the houses of Ashkelon shall they lie down in the evening: for the LORD their God shall visit them, and turn away their captivity”.

-

Zecharia (9:5): “Ashkelon shall see it, and fear; Gaza also shall see it, and be very sorrowful, and Ekron; for her expectation shall be ashamed; and the king shall perish from Gaza, and Ashkelon shall not be inhabited”.

-

Assyrians (8th – 7th century BC)

The Assyrian empire, a rising force in the region, conquered the North Kingdom of Israel in 732BC, destroying most of the cities and villages in the land. The Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III annexed the area (as per 2 Kings 15: 29):

“In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took … and carried them captive to Assyria”).

Tiglath-pileser III names Ashkelon among his tributaries.

The Assyrians reached Ashkelon and made the Philistine cities – from Jaffa to Raphia – a kingdom subdued and raising taxes to the Assyrians. The main city of the Philistine-Assyrian kingdom was Ashdod.

The cities of the Levant attempted to free themselves from the Assyrians, and were assisted by the Egyptians. In 712 the Assyrian King Sargon II came to fight the Egyptian army in Raphia, south of Gaza, and managed to repel them back to the south.

After the death of the Assyrian King Sargon II (722-705 BC), the Judean King Hezekiah mutinied against the Assyrians, joining other cities in the area in another attempt to free themselves from the Assyrian conquest. Two Philistine cities joined Hezekiah’s mutiny: Ashkelon and Ekron. Hezekiah crushed the other Philistine cities that refused to join the mutiny (2 Kings 18:8): “He smote the Philistines, even unto Gaza, and the borders thereof, from the tower of the watchmen to the fenced city”.

The Assyrian army came in 701, led by Sennacherib, son of Sargon II (2 Chronicles 32 1): “After these things, and the establishment thereof, Sennacherib king of Assyria came, and entered into Judah, and encamped against the fenced cities, and thought to win them for himself”. The Assyrians first handled the Philistine cities and confronted the Egyptian army who supported the mutiny. Ashkelon, whose King Zedka led the Philistine revolt, was punished and its ruler was replaced. Sennacherib conquered 46 cities in Judea, but Jerusalem was spared from destruction.

Orthostat relief – depicting soldiers from different orders of the Assyrian Army, in procession;

basalt; Hadatu Tiglath-Pileser III period (744-727BC) [Istanbul Archaeological museum]

The Biblical account was also recorded in Sennacherib’s inscription on a stele, found in the ruins of the royal palace Nineveh:

“And Sidqa, the King of Askelon, who had not submitted to my yoke, the gods of the house of his father, himself, his wife, his sons, his daughters, his brothers, the seed of the house of his father I took away and brought him to Assyria. Sharruludari, the son of Rukibti, their former king, I placed over the people of Askelon, and imposed upon him the payment of tribute as an aid to my rule, and he bore my yoke”.

Sennacherib’s stele with relief and inscription; Ninveh;

limestone [Istanbul Archaeological Museum]

-

Babylonian (630-538 BC)

The Assyrians ruled Ashkelon for 100 years, and were followed by the Babylonian empire (630BC-538BC) and the Persians (538-332BC).

The Babylonian empire rose after the fall of the Assyrians (610BC), defeated the Egyptians (609BC) and conquered the land until the Nile (2 Kings 24 7): “… for the king of Babylon had taken from the river of Egypt unto the river Euphrates all that pertained to the king of Egypt”.

Ashkelon was conquered in 604 BC, and the city was destroyed. Its people, as well as the residents of the other Philistine cities, were relocated to Mesopotamia. This ended the 600 years of the Philistine presence in Israel.

The fortifications of Ashkelon were not rebuilt after the Babylonian destruction, until the end of the Hellenistic period, about 500 years later.

“Lions in Relief” – from the procession street in Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar II period (604-562BC); glazed brick [Istanbul Archaeological Museum]

-

Persians (538-332 BC)

The new power – the Persian empire – replaced the Babylonians in 538 BC. Their King Cyrus allowed the exiled Judea residents to return to Jerusalem and rebuilt the area around it. Ashkelon remained outside of the small Jewish region.

During the Persian period, the former cities of the Philistines were resettled by the Phoenicians who excelled in Maritime commerce. The city was under the patronage of the Phoenician port city of the Tyre. The Phoenicians in return served the ruling Persian empire with Maritime services. This brought great wealth to the port city in the following years.

The excavations of the city unearthed a massive cemetery for dogs, with more than 1000 dogs buried in the southwest section of the city. This was a Phoenician ritual custom connected to healing rites.

-

Alexander the Great (332 BC) and successors – Hellenistic period

When Alexander the Great arrived to the area (332BC), Ashkelon surrendered and was not harmed, unlike nearby Gaza which was totally destroyed after 2 months of siege. The city was named Ascalon, preserving its ancient name. The former area of the Philistines – Pleshet – an area of the sea coast which included Ashkelon, was now called by the Greeks “Paralia”.

After Alexander’s death (323), Ashkelon/Ascalon was torn and switched sides between the two Greek empires – the Ptolemy-Egyptian and the Seleucids-Antioch. Major battles occurred between the sides, starting from the battle near Gaza (312 BC) with the victory of the Ptolemy kings, who ruled the Levant (Israel and Syria) for the following 114 years (312-198).

Greek coin – Alexander the Great – Bethsaida

The Seleucids attempted to recapture the area during the First and Second Ptolemy-Seleucid wars (276-255), and failed again in the Third Syrian war (246-240). In their next attempt (219-217) the Seleucids managed to win several battles, but the Raphia battle in the south (217) secured the Ptolemy control. Ashkelon and the other Philistine cities were captured in 201 BC by the Seleucid king Antiochus III, but the Ptolemy army, headed by general Scopas, pushed them back to the north. The Seleucids finally defeated the Ptolemy army in the battle of Banias (198 BC). This gave them a control of the Land of Israel. Josephus writes about this (Ant. 12 3 4): “Antiochus overcame Scopas, in a battle fought at the fountains of Jordan, and destroyed a great part of his army”.

During the Hellenistic period, and even during the Hasmonean period, Ashkelon/Ascalon remained an independent city. As such, it minted its own coins, starting in 111BC. The city was also known for its beautiful Hellenistic temples.

-

Maccabee revolt and Hasmoneans (167-63 B.C.)

The Maccabees headed the anti-Hellenization rebellion against the Greek Seleucids who controlled the land of Israel since 198 BC. After a series of successful military campaigns they took control of Judea, liberated the land and created an independent Jewish country, known as the Hasmonean Kingdom (164-63 BC as independent state, and 63-37BC as rulers under Rome).

Hasmoneans battle the Seleucid Greeks (Stable Diffusion T2I)

The southern coast cities of Israel were important targets during the following years of the Hasmonean expansion. In 145 BC Jonathan Maccabee captured Ashdod and killed 8,000, and forced a truce with Ashkelon. (Antiquities 13, Chapter 7:4):

“When Jonathan therefore had overcome so great an army, he removed from Ashdod, and came to Askelon; and when he had pitched his camp without the city, the people of Askelon came out and met him, bringing him hospitable presents, and honoring him; so he accepted of their kind intentions, and returned thence to Jerusalem with a great deal of prey, which he brought thence when he conquered his enemies.”.

His brother, Simon, fortified Ashkelon (Antiquities 13 5:10): “About the same time it was that Simon his brother went over all Judea and Palestine, as far as Askelon, and fortified the strong holds; and when he had made them very strong, both in the edifices erected, and in the garrisons placed in them”. Ashkelon was under Hasmonean rule until 137 BC, when it returned to the Seleucid control.

Years later, King Alexander Jannaeus recaptured the area around Ashkelon in 103-102BC (Wars 1 4:2):

“However, Alexander recovered this blow, and turned his force towards the maritime parts, and took Raphia and Gaza, with Anthedon also, which was afterwards called Agrippias by king Herod”. This campaign secured the southwest border of the Hasmonean Kingdom, with a border set at the brook of Egypt, 74 Km (46 miles) southwest of Gaza.

Ashkelon remained during this time an independent city, and was not part of the Hasmonean kingdom. Why didn’t the Hasmoneans incorporate the city into their Kingdom? Perhaps, due to the alliance of the city with the Egyptian Ptolemy rulers, who sided the Hasmoneans against the Seleucids.

- Early Roman Period (63BC – 67 AD )

Pompey captured the land in 63 BC, and rearranged the territories. Ashkelon retained its independent city status even during the Roman period. It flourished as a major commerce port city, and grew again to the former Canaanite size of 600 Dunams (60 Hectares). During the Late Roman period, the Roman city walls were built over the Canaanite glacis.

Herod the Great, King of Israel under the Romans (37BC – 4BC), was a great builder. Most of his impressive projects are in Israel (such as the grand temple), but he also built in foreign cities, including in Ashkelon (Wars 1 21:11):

“And when he [Herod] had built so much, he showed the greatness of his soul to no small number of foreign cities. He built palaces for exercise at Tripoli, and Damascus, and Ptolemais; he built a wall about Byblus, as also large rooms, and cloisters, and temples, and market-places at Berytus and Tyre, with theatres at Sidon and Damascus. He also built aqueducts for those Laodiceans who lived by the sea-side; and for those of Ascalon he built baths and costly fountains, as also cloisters round a court, that were admirable both for their workmanship and largeness”.

In his will, Herod bestowed his sister a villa in Ascalon (Wars 2 6:3): “Caesar did moreover bestow upon her the royal palace of Ascalon”. A Christian tradition, perhaps based on Jewish sources, identifies Ashkelon as the birthplace of Herod in 73 BC, which could explain these acts and why Ashkelon was left as an independent city. This tradition gave Herod a nickname Ish-Kalon (Hebrew: man of shame, rhymes with Ash-Kelon), as Herod was also known for his cruelty.

- Great Revolt (67-70 AD), Roman period (1st C-4th C AD)

During the first stage of the great revolt against the Romans, the Jews were attacked in Ashkelon and other Hellenistic cities, in response to the conquest of Jerusalem and other sites in Judea (Wars 2 18 5):

“…the other cities rose up against the Jews that were among them; those of Askelon slew two thousand five hundred”.

As a response, the Jewish rebels burnt the city (Wars 2 18 1):

“…some cities they destroyed there, and some they set on fire, … nor was either Sebaste [Samaria] or Askelon able to oppose the violence with which they were attacked; and when they had burnt these to the ground; they entirely demolished Anthedon and Gaza; many also of the villages that were about every one of those cities were plundered, and an immense slaughter was made of the men who were caught in them”.

Roman soldier – in Jaffa museum

During the battles (66 AD), the rebels attacked Ashkelon (Wars 2:1,2):

“Now the Jews, after they had beaten Cestius, were so much elevated with their unexpected success, that they could not govern their zeal, but, like people blown up into a flame by their good fortune, carried the war to remoter places. Accordingly, they presently got together a great multitude of all their most hardy soldiers, and marched away for Ascalon. This is an ancient city that is distant from Jerusalem five hundred and twenty furlongs, and was always an enemy to the Jews; on which account they determined to make their first effort against it, and to make their approaches to it as near as possible. This excursion was led on by three men, who were the chief of them all, both for strength and sagacity; Niger, called the Persite, Silas of Babylon, and besides them John the Essene. Now Ascalon was strongly walled about, but had almost no assistance to be relied on [near them], for the garrison consisted of one cohort of footmen, and one troop of horsemen, whose captain was Antonius”.

Antonius managed to defeat the Jewish forces:

“Now the Jews were unskillful in war… the fight lasted till the evening, till ten thousand men of the Jews’ side lay dead”. The Jewish rebels attempted a second assault, which also failed (Wars 2: 3): “…they got together all their forces, and came with greater fury, and in much greater numbers, to Ascalon. But their former ill fortune followed them, as the consequence of their unskilfulness, and other deficiencies in war; for Antonius laid ambushes for them in the passages they were to go through…”.

Vespasian, head of the Roman army that crushed the revolt, secured the coastal area in 67 AD.

Marble statue of Mercury – Roman God of Commerce –

Found in Ashkelon 84 cm high; 2nd C AD; [Lib. of Congress, 1900]

Jewish presence in the city continued after the tragic results of the revolt. Remains of a synagogue were found in the excavations.

Roman highways: The coastal road passing near Ashkelon, connecting the north to Egypt, appears on the Peutinger map. This map is based on a 4th century Roman military road map, with an orientation of north on the right side. Jerusalem is marked by a pair of icons of a house with “Herusalem” above it.

Ashkelon is also marked with a pair of icons with “Ascalone” above it. The double-icon symbol shows the importance of the city. Two roads pass through the city – north-south along the coast, and east towards Jerusalem.

Peutinger Roman 4th century Military Map – section near Ashkelon written in Greek as “Ascalon” (above the top twin houses).

Note that the map is oriented with north on the right side.

-

Byzantine period (4th – 7th century A.D.)

During the Byzantine period, the city converted to Christianity. The port city was a center for trade in fine wine and grain. Scallion, the spring onion with hallow green leaves, was cultivated here and named after the city.

Ashkelon appears in the Madaba map, an ancient map of the Holy Land from the 6th century AD was discovered in 1884 in a Byzantine church in Madaba, Jordan. The name of the city appears as Ackal[on], seen here on the upper part of the segment.

![]()

p/o Madaba map

The major streets, public and religious buildings of Ashkelon are illustrated on the mosaic. Its elaborate details and size (comparable to Jerusalem) imply the importance of the city. The illustrations show:

- Eastern gate flanked by towers;

- A square;

- A public building

- Two main intersecting colonnaded streets (Cardo, Decamanus)

- The city walls and a tower.

On the upper side are a few letters, reference to the Church of the Three Egyptian Saints.

- Arab period (7th-12th century AD)

In 637 AD Ashkelon was conquered by the Arabs, completely destroyed, ending its Christian population and importance.

The city was rebuilt and fortified in 685. The residents included Muslims, Christians, Jews and Samaritans. Friction between these communities caused occasional conflicts, such as the burning of a church in 937.

During the next years the city became an important wealthy Muslim city, thriving from the growing commerce between the south and the north.

- Crusaders (12th -13th century)

The Crusaders arrived from Europe to the Holy Land in order to liberate the Holy Land and free Jerusalem. They accomplished the mission in 1099, and established the Crusader Kingdom.

Ashkelon was on the border between the Arabs in Egypt and the Christian Crusaders in the Holy Land. Long battles were fought among the armies near the city, including the great battle of Ashkelon (1099) when the Crusaders first established the southern border of their Kingdom in the Holy Land.

After holding the city for a while, they retreated to the east of Ashkelon. During the next 12 years (1101-1114) the Egyptians attempted to retake the Holy Land, attacking the Crusaders for 10 times, with battles around the city. In 1125 the Crusader forces headed by King Baldwin II tried to capture Ashkelon, but failed due to its mighty fortifications. They succeeded only in 1154 with Baldwin III, and made it an important fortress named Ascalona (or Ascalonitane).

The Crusaders were surrounded by the hostile Arab world, and therefore the importance of holding and fortifying the city which was located in the border of their Kingdom.

Crusaders fight Arab forces – AI generated by Bing

The beginning of the end for the Crusaders was on July 4, 1187, in the battle of Hittim, won by the forces of the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin. Ashkelon, as other Crusaders strongholds, was soon taken (on Sep 4, 1187) after a two week siege. Saladin then turned to systematically destroy the fortifications in order to prevent the Crusaders to use it block the approach from Egypt.

Richard I the Lion heart of England recaptured it in 1191 following his victory in the battle of Apollonia (Arsuf), but Saladin demolished its fortifications before the Crusaders entered to the city. Richard then restored its walls, but then the Arabs destroyed them again.

Ashkelon was refortified only in 1240 by his relative, Richard 1st Earl of Cornwall (Cornubie), the second son of John, king of England, and brother of King Henry III. It held until 1247 when the Ayyubid forces conquered the city.

- Mamlukes (14th-16th century)

The fortifications of Richard of Cornwall were the last fortifications of the city. In 1270 the Muslim forces leaded by the Mameluke king Bybars captured and demolished it, and filled up the port of Ashkelon, and left it desolate. This act of destroying the Crusader castles followed their global strategy to destroy all port cities along the Levant coast in order to prevent the Europeans to return to the Holy Land.

Ashkelon was never built again, and its rediscovery waited until the 19th Century. Sadly, most of its stones were looted, and reused in structures across the country.

Two Arab towns, Maj’dal (“tower”) and el-Jurah (“the pit”), were established during the Mameluke period, north-east of ancient Ashkelon. They were resettled by Egyptian immigrants. During the late 19th Century, the town of Maj’dal became a center of the weaving industry.

-

Ottoman period (16th – 20th century)

Ashkelon was first excavated in 1815 by Lady Hester, an adventurer who searched for buried treasures. The site was then surveyed by Roberts (1839) and Guerin (1854), followed by the PEF survey of Conder and Kitchener (1875, – as detailed below).

David Roberts, a Scottish painter (1796-1864), visited Ashkelon in 1839 and illustrated the site. His vantage point was on the ruins of a Church, near the Canaanite gate on the north west corner, gazing southwards. The ruined walls on the east and south are visible in the far background. The foundations of a large colonnaded building in the center was probably excavated earlier by Lady Hester, and later exposed by Egyptian general Ibrahim Pasha who reused the stones for his command center east of Ashkelon (years 1832-1840). Note that this structure, as well as other sections within the city walls, was covered by farm land and was not visible to the PEF survey team 36 years later.

On the right edge of the drawing, overlooking the sea, is a small structure called El Khudra in the PEF survey.

Ruins of Ashkelon, Illustration by David Roberts, 1839 [Library of Congress]

-

Survey of Western Palestine

Conder and Kitchener of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) surveyed the area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) in 1874-75. The report of the ancient sites of Ashkelon is found in sheet XIX (Volume 3, pp 238-247). Sections of the report are brought here:

” Askalan The famous walls of Richard Lion-Heart, built in 1192 A.D., are still traceable, and in parts standing to a considerable height. The town is bow-shaped, measuring of a mile along the string north and south, and 5/8 of a mile east and west, the total circumference being 1 3/4 miles.

The walls are, on the south especially, covered by the rolling sand. The interior is occupied by gardens, and some 10 feet of soil covers the ruins. Palms, tamarisks, cactus, almonds, lemons, olives, and oranges are grown, with vegetables, including the famous shallots, named from the place. There are also a few vines. The place is well supplied with sweet water. In the gardens there are 37 wells, each some 3 feet diameter, and in some cases over 50 feet in depth. By each is a cemented reservoir, and a wooden roller for the rope. Marble shafts have been used up for fixing the ropes, and by each well is a capital of marble which has generally the appearance of Crusading work.

Quantities of masonry pillars and sculptured fragments are found in digging to a depth of some 10 feet. Inscriptions on slabs of white marble have also been discovered. There are many fine shafts of grey granite, some 3 feet diameter and 15 feet long, lying among the ruins in various parts. Many have also been used as thorough-bonds in the walls. The masonry of the walls is throughout small, and the stone a friable sandy limestone, but the mortar used is extremely hard and full of black ashes, and of shells from the beach ; the walls have fallen in blocks, and the stone seems to have given way in preference to the cement.

There is no harbour, but on the coast are rocky precipices from 20 to 70 feet high. To the south near the jetty there are reefs of rock below the water. The lowest part of the town is between the ruined church in the north-west corner and the sacred Mukam of el Khuder. A sort of valley here runs down, and the cliffs above the beach are lower. The cliff in the north-west corner is the highest part.

There are remains of five towers on the land side of the wall. In the north-west corner of the town are remains of a wall, with a deep masonry well 4 feet diameter, beside which is a cistern. A large ruined tower is situate 150 yards north of the mainland entrance. It is 40 feet square, with round turrets 12 feet diameter in the north-east and south-east corners. The interior is supported on vaults ; the turrets were solid at the base. At an equal distance south of the gate is a tower projecting 28 feet, and 34 feet wide outside. The wall south of it is carried back 28 feet, so that flank defence is obtained on that side. At the south-east angle of the wall is a fourth ruined tower ; a fallen block of masonry is alone visible. Near the south-west corner of the fortification is a tower 50 feet broad, projecting 64 feet, and apparently there was here a postern gate”.

Part of map Sheet 19 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

“In addition to the towers there were buttresses on the walls, apparently at intervals of 100 feet. These projected 8 to 13 feet, and were 4 feet wide. There are also on the east three large buttresses, 24 feet by 6 feet 9 inches, and south of the main gate is a wedge-shaped buttress 14 feet thick at the back, 2 feet in front, 17 feet along one side, 13 feet along the other. The eastern or land gate is constructed like most of the twelfth century fortress gates, in such a manner as to secure flank defence. The entrance was from the south, in a wall running out at right angles to the main wall east and west. There are remains of an outer wall east of the main wall about 35 yards from it, and this appears to have covered the entrance. The angle between the main wall and that projecting from it was strengthened by a polygonal tower on the south, foundations of which remain. A block of masonry lies fallen on one side . It is 20 feet diameter, and 5 feet 9 inches in height, being apparently the base of a turret, probably flanking the gate. This must have been overthrown by violent means, probably in the destruction of the walls by Saladin, according to the treaty of 1192 AD. Excavations have at some time or other been made at this gate, and at the tower on the wall north of it.

The sea gate is in the sea wall, near the south-west corner of the fortifications. The same care is shown here also in constructing the entrance. There is an outer wall running parallel with the west wall. It is 3 1/2 feet thick, and the clear space between is 9 feet. It appears to have extended for 66 feet. A wall also runs out from the main wall, and joined the outer wall apparently at its south end. The gate in the wall is immediately north of this projecting wall, and on its north side is a buttress projecting 2 feet, and at a clear distance of 8 feet from the projecting wall. The passage thus formed protects the gate either side, and a party approaching had first to proceed south for 66 feet, and then turned east through a passage 8 feet wide, and entered the gate, which was only 3 feet wide. A tower stood on the wall north of the gate, and projected inwards for 22 feet, forming an internal flanking defence to the gate. Inside this tower was a vaulted cistern, 7 feet east and west by 19 feet north and south, lined with hard white cement”.

PEF report (V3, page 238) – map of 19th century Ascalon

The report continues:

“Steps led up the side of the precipice to this sea gate, and below a small jetty ran out into the water. It was formed, like that at Caesarea, of the shafts of granite pillars laid side by side. Similar shafts project from the walls all along the sea face of the town, for the ashlars has here been either removed or disappeared, and only the rubble core of the walls remains, with the pillars sticking out from it.

In the north quarter of the town are remains of a church. The bearing is 94° west, and traces of one of the apses were visible. The walls remain, running in the direction stated for 60 or So feet, and, on the north, part of the wall is standing to a height of some 6 or 8 feet ; but the plan is now not distinguishable, and the ashlar has been taken away, leaving only rubble. Inside the church are several pillar bases of white marble, which have been dug up. They have on them marks which resemble Phoenician letters, and which are cut on the upper sides, so that they were covered by the bottom of the shaft of the pillar.

The remaining ruins are of less importance. There is a small building on the cliff, further south than the church, to which the name el Khudra is now given. It measures 9 paces either way, with an entrance on the north, on which side is a porch of the same size. The windows of the building have round arches, and it may perhaps be of early date. Between it and the sea, on the edge of the cliff, is a grave, apparently modern. In the south quarter of the town are the foundations of a large building, measuring 37 paces along a line 112° west, and 15 paces at right angles. It has a projection to the east, as if there had been an apse. But the masonry has a comparatively modern appearance….

Visited 3rd, 9th, and 10th of April, 1875″.

- Archaeological scientific excavations

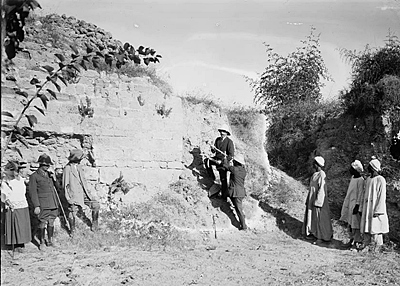

First scientific excavations were held by John Garstang of the Palestine Exploration Fund (1920-1922) during the British Mandate. The high commissioner for Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, was the guest of honor in the commencement ceremony – as seen on this photo.

Large scale excavations are conducted by the Leon Levy expedition since 1985.

The IAA conducted underwater and coastline surveys (1992-1997, 1996-1997) but did not find a constructed harbour, concluding that the ships moored in the open sea and their goods were carried out by small boats.

Sir Herbert Samuel breaking the sod for commencement of excavations at Ascalon, 1920

– American Colony, Library of Congress collection

-

Modern Period

The modern city of Ashkelon was established in 1949, after the Independence of Israel. Its center is located to the north of ancient Ashkelon. Today (2014) it has 128,000 residents and the large city covers an area of 55,000 dunams (5,500 Hectares).

The national park of Ashkelon was established in 1964, the first park declared in the newly founded National Park Authority.

Photos:

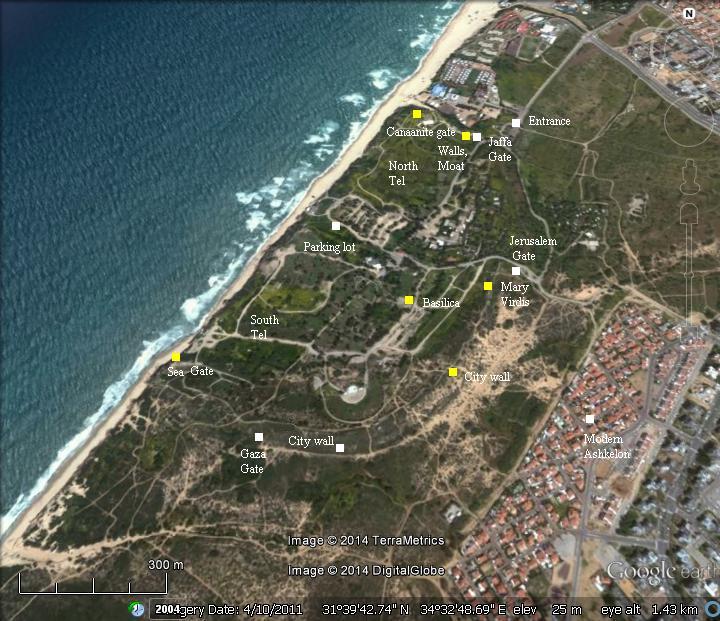

(a) Aerial Views

The North-west corner of the park is shown in this drone photo. The ruins of this large ancient city stretch 1,100m to the south, so the southern edge cannot be seen in this shot.

On the left is the Canaanite gate and glacis walls, with ruins of the the Medieval walls behind it. On the right side is a view of the cliffs above the coastline.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

On the south side of the park is the Basilica, an apsidal building and other remains of the Roman city. The aerial view is towards the north:

The next aerial photo is captured from the same spot, but with a view towards the south east. It shows the large restored theater, and the southern and eastern walls stretching left to right behind it. The residential houses of the city of Ashkelon are seen in the background.

![]() A collection of aerial views of the national park can be seen in the following YouTube video. Its starts with a view from the north side, then above the south west side, and finally over the south east side.

A collection of aerial views of the national park can be seen in the following YouTube video. Its starts with a view from the north side, then above the south west side, and finally over the south east side.

(b) Canaanite City fortifications:

The Canaanite city, established in ~1950 BC, was protected by three lines of defense along its circumference: a deep moat in the exterior, followed by a glacis covering a steep earthen rampart, then ending in high walls above the glacis.

The total length of the ramparts was 2200 m (1.25 miles), covering the north, east and south sides of the hill in a semicircular plan. The sea side (western) defense was based on the natural cliffs.

The wall is best preserved on the north-west corner, where a formidable gate was discovered.

In the following photo is a closer view of the rampart near the north-west Canaanite gate.

The Canaanite rampart was 15m (50ft) high and 46m (150 ft) thick. During the Middle Bronze age, the Canaanites moved enormous amount of earth to create these huge artificial slopes around the entire sandstone hill on which the city was located. The slope was 33-35 degrees on the outer face, make the attackers’ ascent difficult.

The earthen rampart was first laid with mud bricks, creating a glacis. At a later stages (three phases) the glacis was covered by an outer face of rows of fieldstones sealed with a smooth layer of rammed earth and plaster, to give the slope a smooth and slippery surface. These slopes made the ascent difficult for the assailants, kept them in an open area for the archers, while also strengthening the walls against undermining.

The slope also prevented the use of the battering ram, an instrument which was already in use in the Early Bronze age to knock down the fortifications.

Remains of a Canaanite sanctuary were found within the stone glacis, near the road leading from the beach to the city gate. The sanctuary was used by the Canaanite residents of the city and by the sea-going people. To ensure a safe journey on sea, the sailors would pray in this sanctuary before departing to their voyage, or thanking the deity after returning safely to port.

Inside the storeroom of the sanctuary, a small statuette of a bull calf was found inside a shrine shaped clay vessel. Its size was 10.5 cm (4 inches) long and 10.5 (4 inches) high, weighing 400 gram (a pound). The bull calf was made of bronze and silver coated. It is identified with the Canaanite God of storm – Baal (“master”), also known as Hadad (God of thunderstorms). Baal is often associated with a bull, hence the form of the statue.

Worship of the bull calf is known from the Bible:

-

the Golden calf during the Exodus (Exodus 32:4):

“… after he had made it a molten calf: and they said, These be thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt”.

-

Hosea warns against the practice of kissing of calf images (Hosea 13:2 ):

“And now they sin more and more, and have made them molten images of their silver, and idols according to their own understanding, all of it the work of the craftsmen: they say of them, Let the men that sacrifice kiss the calves”.

Vessel and silver statue of calf – Courtesy of Ashkelon National park

The photo below shows the location of the sanctuary, which is marked by a flag. It had 6 small rooms organized along two sides of a courtyard, with a total area of 8.7m x 10.5m. The silver calf was found in the northwest room.

The sanctuary is located near the gate, just above the sloped road going west towards the port. This road, 6 meters (20 feet) wide, ascended from the nearby harbor up to the gate at the top of the rampart.

A deep moat (6-8 meters , 20-26 feet deep) was cut into the ground just before the glacis and below the access road. The purpose of the dry moat (the deep, broad ditch just before the road above it on the right) was a first line of defense – keeping the battering ram and other siege weapons away from the walls. It also made the use of sapping (or, mining) under the ramparts more difficult, thus preventing the enemy to build tunnels under the walls in order to collapse them or to sneak into the city.

The modern access path leads to the Canaanite gate, located under the roof in the center of the photo.

Above the ramparts that surrounded the Canaanite city was a high wall, two or three stories high. A view from the top of the wall, towards the access road below, is seen here.

A panoramic view, as seen from the north side, is shown in the following picture. If you press on it, a panoramic viewer will pop up. Using this flash-based panoramic viewer, you can move around and zoom in and out, and view the site in full screen mode. Hot spots indicate the major points of interest.

To open the viewer, simply click on the photo below. It opens a new window, and will run after a minute or so.

(c) Canaanite City Gate:

Inside the rampart the archaeologists discovered the city gate, which is dated to 1825 BC (Middle Bronze IIa, or late 12th Dynasty). This is the oldest arched gate known in the World, and one of the most valued findings in Tel Ashkelon.

The gate was found in 1993 by Prof L. Steiger (Harvard University) , and reconstructed by the IAA Conservation Department and other groups in 2006. Today the visitor can pass through this ancient gate into the city, just like in the ancient times.

The arched gate is 15 meters (50ft) long, over 2 meters (6 ft) wide, and almost 4 (13 ft) meters high. It is built mostly of sun-dried mud bricks, with some calcareous limestone.

The gate was actually constructed in four phases, where each gate was superimposed on top of the earlier gate. This process spanned (roughly) from 1825-1775 BC (Gate 1), 1775-1725 (Gate 2), and 1725-1650 BC (Gate 3 – the largest in the sequence). During the last phase (1650 BC) the gate was converted to a small foot bridge, while the north gate was moved to the east..

- North Exterior side:

People arriving from the port, or from the northern road, would pass through this gate.

A closer detail of the mud bricked wall on the left side is seen here:

The right side of the gate is in the following photo:

The gateway was built into a large brick wall, just above the earthen rampart. The top of the arch collapsed in ancient times, and was filled in, thus preserving the gate. In order to reconstruct the arch without adding weight to the gate, the conservation team decided to use a wooden frame for the reconstructed arch, covering it with a layer of plaster.

- Inside the gate:

A view back towards the entrance is in the following photo. Notice the mud brick walls along the sides of the gate, which are towers that flanked the gateway as a second story. These walls reach a height of 6 meters (20 feet).

The width of the gate is 2.5 meters (8 feet) and its height is 3.5 meters (12 feet). This allows a standard Bronze period wagon to pass through the gate.

- South inner side:

The following photo shows the inner (south) side of the arched gate. The reconstructed arch is based on wood, but without plaster as on the north side.

A closer view of this side of the gate:

The gate reaches to the level of the city. The conservation team consulted with a landscape designer to build this beautiful design.

After the Canaanite period, the Philistines rebuilt the fortifications above the rampart which covered the Canaanite gate. These fortifications included mud brick towers which continued to be in use until 700 BC.

(d) Harbor

Ashkelon was a port city, and the harbor played an important role in its history. The ancient port is located somewhere along the shore to the west of Tel Ashkelon. Its location was not yet found, in spite of thorough underwater surveys and archaeological surveys along the beach. Since it is buried deep under the sediment and the sand, its location is still a mystery.

The harbor’s location may have changed during the history. During the Canaanite period, it may have been located to the west of the Canaanite north gate and later moved south. Another theory is that the Canaanite harbor was located near the center of the Tel (under the modern parking lot), where there is a cavity between the north and south sections. That cavity separated Tel Ashkelon to two sections, named by the Leon Levy Expedition as the “North Tell” and “South Tell”. Between these two sections, the harbor may have existed during the Middle Bronze period, and has submerged and covered by land.

In later periods, from the Hellenistic to the Medieval periods, the port may have been relocated to the south west side of Tel Ashkelon, near the Sea Gate. That harbor was not built, as no breakwaters were found. The large ships would have anchored in the open sea, the small boats would have unloaded the cargo and ship them inland. During the Crusaders period, some evidence of an anchorage point was found near the southwest corner.

The next photo shows the access from the northern city gate to the beach.

A view from the beach to the northern side of Tel Ashkelon is seen below. The natural sandstone (Kurkar) cliff was a natural defense, and so no massive walls were required on this side.

A section of the west side of Tel Ashkelon are seen in the following photo. Traces of ruins can be seen on the upper level of the cliff.

(e) North Walls:

Ruins of the Medieval walls and towers are also located on the north side of the mound, located to the east of the Canaanite gate. All the late periods – Hellenistic, Roman and Islamic periods – follow the same line of the Canaanite ramparts.

These segments may have been part of the towers that once protected the Jaffa (North) gate. The walls are more than 2 meters (6 feet) thick, composed of stones bonded together with mortar (like cement). Some of the walls reused ancient marble pillars that are embedded into the mortar, in order to reinforce the walls. The estimated size of each tower is 25 meters square.

Also on this side is the stone glacis of Islamic Ascalon, built in the Fatimid period (10th and 11th Century) and later rebuilt by the Crusaders (1240-1241) by Richard of Cornwall.

Just like the Canaanite glacis, which is seen in the far background of the photo below, the sloped wall had important military purposes that did not change in the course of the 3,000 years.

A large moat, 25 meters wide and 9 meters deep, is located to the north of the moat – again repeating the Canaanite method.

Another view of the north walls and glacis are seen below.

(f) West:

The west side of Tel Ashkelon stretches along the shore. About 300m to the south of the north most point of the Tel is a valley.

Ruins of a small Medieval structure are located on the edge of the cliff, which could have been a small temple or shrine. It is named Maqam al-Khadra – the Green shrine. The PEF report of 1875 writes about it (V3, p 240):

“There is a small building on the cliff, further south than the church, to which the name el Khudra is now given. It measures 9 paces either way, with an entrance on the north, on which side is a porch of the same size. The windows of the building have round arches, and it may perhaps be of early date. Between it and the sea, on the edge of the cliff, is a grave, apparently modern”.

This shrine, as well as dozens along the coast, were part of a Mameluke plan to erect Muslim shrines along the coast line, as part of their strategy against the Crusaders. Another Muslim structure, Sheikh Awad near the beach of Ashkelon, was another such structure.

A well is located near the shrine:

A public beach is located to the west of the parking lot.

(g) South West:

In the southwest section of the Tel, also named “the South Tell”, interesting findings were excavated. The excavations reviewed ancient structures in various levels of settlements.

One of these interesting findings is the cemetery for dogs, with hundreds of burials dated to the Persian-Phoenician period. This was found in this area at the edge of the Tel, about 300m north of the southwest corner. Of the total of 1,238 dog burials found, 970 of them were found in grid #50 – west of an earlier warehouse. This custom of burying dogs is found elsewhere in the region, especially in Egypt, but the unusual practice of burying large numbers of ordinary dogs was probably a local innovation.

On the south west side of Tel Ashkelon is the “Sea Gate”. Sections of the Muslim and Crusaders wall are visible here.

In the ancient wall are Roman marble columns that were used to strengthen the walls.

The PEF report of 1875 wrote about this: “There are many fine shafts of grey granite, some 3 feet diameter and 15 feet long, lying among the ruins in various parts. Many have also been used as thorough-bonds in the walls”.

Another excavation area is located on the southern foothill, where a continuous sequence of occupation existed from the Iron Age through the Late Byzantine period. In most of these periods, this area was a residential quarter close to the city wall.

In the lower side of the area, the excavators found the ruins of a Persian period building. The floors are paved with sun baked mud bricks. In an upper level, a Byzantine period villa was found overlooking the sea, with floors of mosaics and ceramic tiles.

A road leads from the southwest side to the center of the city.

Along the road is a marble base of a column. Notice the mason mark on the base.

(h) Center:

In the center of Tel Ashkelon is a wide green area, a place for visitors to enjoy leisure time and a wide playground. Overnight stay is also available, and many come here to pitch tents and stay over a night or two.

Traces of the south walls are visible on the edge of the national park. These walls are dated to the Muslim and Crusaders period.

Remains of the Medieval walls are also seen inside the city.

(i) Basilica:

In the center of the park are remains of a Basilica – an impressive colonnaded structure, dated to the Roman period. The structure is 100 meters (328 feet) long and 35 meters (114 feet) wide.

This was a courtyard which was surrounded by parallel rows of columns and chambers. The structure was covered by marble. This grand public place was where the residents of the Roman city conducted here business and social life activities.

In 685 AD the structure was converted to a Mosque.

A lovely marble statue was found here, with Nike (Roman goddess of victory) standing on an orb (sphere), which is supported by Atlas (Greek Titan, who held the World).

Another nice piece of Nike, holding a palm tree leave on the left side:

A collection of other marble columns is located near the offices of the national park, north of the basilica.

(j) Apsidal building:

South of the basilica was an apsidal building, dated to the early 3rd Century AD. This semicircular structure may have served as a meeting hall for the town council.

Recent excavations also unearthed a Herodian basilica and a small Odeon – a roofed mini-theater which was used for musical shows, poetry reading, poetry competitions and singing exercises.

(k) Wells:

Tel Ashkelon has no springs in or around the site, but it is blessed with abundant groundwater. Its hydro-geological position of the site, located at the end of groundwater flow from the coastal lowland to the sea, provides an easy access to the underground water level.

Dozens of wells inside the city extracted the water, and the ancient city of Ashkelon was famous for its water resources. During the ancient times, water supply was one of the most important requisites for sustaining life in the fortified cities, and the local supply of fresh water gave Ashkelon an important asset.

The earliest known well is a Philistine well, located in the southwest part of the Tel. Most of the wells have been constructed in the Byzantine period.

The surveyors identified 51 wells, but assumed that many more were covered over the years. The average depths of the wells is 18-27m (66% of the wells) and 10-17m (33% of the wells).

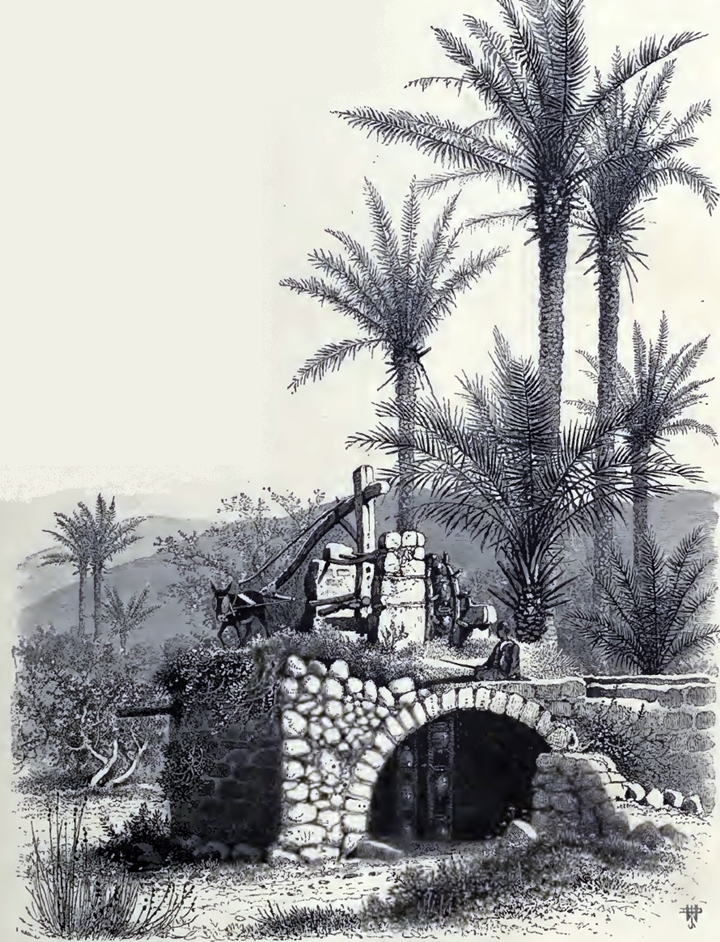

After the destruction of the Crusader city, the water supply was used for irrigation of the agriculture fields on top of the hill. The PEF report of 1875 wrote: “The place is well supplied with sweet water. In the gardens there are 37 wells, each some 3 feet diameter, and in some cases over 50 feet in depth. By each is a cemented reservoir, and a wooden roller for the rope. Marble shafts have been used up for fixing the ropes, and by each well is a capital of marble which has generally the appearance of Crusading work”.

One of the most impressive well (#46) is located in the center of the Tel, close to the basilica parking lot. Another similar installation is located near the sea gate. In total, 7 well-houses were found. This water-house is dated to the Ottoman period, and was in use until the early 20th Century.

- Antilia well

The water wheel, also known as “Antilia”, was one of the devices used to fetch the water from the bottom of the well. This type of installation used cogwheels and animal power – donkey or camel – to raise water from the well, and let it fill up a pool. From the pool the water was channeled to agriculture fields, or used for household or livestock.

The word “Antilia” is based on a Greek word for raising water. In Modern Greek αντλία (antlía) means ‘pump’. The Greek word was used in ancient times to describe this type of well, as many other Greek and Aramaic words were added to the local language during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. For example, the late 2nd Century compilation of Jewish oral law, the “Tosefta” or “supplement”, disqualifies waters fetched by such well for use in a Mikveh (ritual bath), as opposed to spring or stream water which are permitted sources (in: mikveot 84).

Thanks for R. Mendrea for questioning this term.

On the side of this well is a round area where the animal turns around, pulling a horizontal beam. The beam, connected to a horizontal cogwheel, which moved a vertical cogwheel.

The vertical cogwheel would in turn to move a type of conveyor belt – a chain that held wooden buckets or clay jars. The chain was draped over the wheel, which was installed on the flat roof above the shaft. The buckets would move with the chain, dip into the water and bring it up, then pour the water into a channel that would convey the water to the pool.

An illustration of a similar animal-operated well, dated 1882, was published in a book by CH. W. Wilson , one of the PEF explorers. The title: “A well in a garden”. The subtitle is: “Showing a machine, called a sakiyeh, raising water to fill the adjacent tank, on the right.”.

Ch. W. Wilson, Picturesque Palestine, 1882, Vol III P. 81

(l) East Walls:

Along the east and south are ruins of the Medieval walls.

Visitors can walk along the path, and admire these massive fortifications. These city walls were built in the 12th Century by the Fatimids in order to defend the city against the Crusaders. All the late periods – Hellenistic, Roman and Islamic periods – follow the same line of the Canaanite ramparts.

The Crusaders strengthened the walls and rebuilt some of them after conquering the city in 1154. The Mamelukes knocked them down in 1270 in order to prevent the Crusaders to return back to the Holy Land.

The walls are more than 2 meters (6 feet) thick, composed of sandstone stones bonded together with mortar.

Some of the walls (like the one below) reused ancient marble pillars that are embedded into the mortar, in order to reinforce the walls.

On the side of the exit road are remains of a tower, one of 54 towers of Medieval Ashkelon.

This tower protected the eastern gate, and was known as the “Jerusalem” gate, as the road passing at the gate directed towards Jerusalem. In the walls of the city there were four gates – Sea Gate (West gate), Gaza (South gate), Jerusalem (East) gate and the Jaffa (North) gate.

(m) Santa Maria Viridis Church:

Along the eastern wall, adjacent and south to the ruins of the Jerusalem (east) gate, are remains of the small Byzantine church called “Santa Maria Viridis”. It was not seen before by the PEF survey, and discovered by chance during the excavations of 1985 while trenching against the inner face of the Medieval ramparts.

The name “Viridis” means green, or: young. The meaning of “green” (as per V. Tzaferis and L. E. Stager) may refer to agriculture, or to the color of a local sports team.

This Church was built in the Byzantine period, at the 5th Century AD. It continued to be in use through the Early Muslim, until a combined mob of Muslims and Jews destroyed it in 938 AD. The Crusaders rebuilt it in 1153, and was one of five Churches of the Crusader city. It was demolished by Saladin’s army in 1191.

The original plan was a basilica – a central nave and two aisles – separated by two rows of three columns each. The apse faces Jerusalem on the east, hence it is next to the city wall. Its six granite columns, made of Aswan granite, supported a gallery and a pitched roof. Water flowed from the apse, through a lead pipe and basin, then reached a marble lined cruciform baptistery built into the marble floor.

The plan was changed during the Crusaders period, to contain four columns and a cruciform vaulted (arched) ceiling above the apse.

Murals on the central apse and two side walls contained colorful icons of four saints, holding scrolls with Greek inscriptions.

A panoramic view, as seen from the eastern walls, is shown in the following picture. If you press on it, a panoramic viewer will pop up. Using this flash-based panoramic viewer, you can move around and zoom in and out, and view the site in full screen mode. Hot spots indicate the major points of interest.

To open the viewer, simply click on the photo below. It opens a new window, and will run after a minute or so.

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of Ashkelon and the area:

- Ashkelon (Ashqelon, Askelon) – perhaps the name is based on the unit of weight – Shekel – as the city was a major maritime stronghold

- Ascalon – Greek name.

- Pleshet – Hebrew name of the Philistine region.

- Paralia – Greek name of the area of the former Philistine region.

Links and References:

* External links:

-

Old photos of Ashkelon – Library of Congress collection

-

National Park and guide with map

-

Recent discoveries at Ashkelon (pdf, 20 pages; Univ. Chicago 1995)

-

Leon Levy expedition – home page – with rich reports, photos, more. The “Ashkelon 1-4-” reports are must-reads!

-

2008 season report – (pdf, 126 pages)

- Crusader-era Siege Ramp Protected Israeli City From the Desert for a Thousand Years – Haaretz, 2021

* Amarna letters:

- Tel el-Amarna letters – high resolution images

- Tell el-Amarna period – Carl Niebuhr (1903) – pdf, 62 pages

- Amarna letters in Reshafim web site

- Hi-Res images of the letters – Museum of Berlin (more than half of the tablets were acquired by the museum)

* Internal links:

- Ashkelon city – overview

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- The Crusaders – overview and their sites

BibleWalks.com – Search for the lost cities of the Bible

Gaza <—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next Shefela site —>>> Ashkelon city

This page was last updated on Apr 23, 2024 (add link, new photos)

Sponsored links: