A large archaeological site in the Judean Shephelah region, with remains of a rich Early Roman period rural settlement and a Byzantine church.

Home > Sites > Judea > Park Adullam >Horvat Midras

Contents:

Overview

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Columbarium

* Church

* Burial Cave

* Synagogue

* Pyramid

* Burial Cave 2

* Columbarium 2

* Hiding complex

* Video

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Horvat Midras, also known as Khirbat Durusiya, is an ancient archaeological site located in the Judean Hills of Israel. The site is situated approximately 22 kilometers southwest of Jerusalem and 7 kilometers northwest of Beit Guvrin.

Founded in the early Hellenistic period (3rd century BC), it grew to a large and rich Jewish rural settlement in the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD, when it was destroyed in the Bar Kokhba revolt. A small Christian community erected a church in the 5th-6th century, but destroyed in the 7th century AD.

The site contains several structures, including a synagogue, a large cistern, and a bathhouse, which are believed to have been built during the Roman period.

The synagogue at Horvat Midras is particularly notable for its impressive mosaic floor, which depicts various scenes from the Bible, including the binding of Isaac and the parting of the Red Sea. The synagogue also contains several inscriptions in both Hebrew and Aramaic, which provide valuable insights into the religious and social life of the Jewish community that once lived in the area.

Excavations at Horvat Midras have been ongoing since the early 20th century and have yielded a wealth of information about the ancient history of the region. Today, the site is open to visitors and is managed by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, and is part of the Adullam park.

Location:

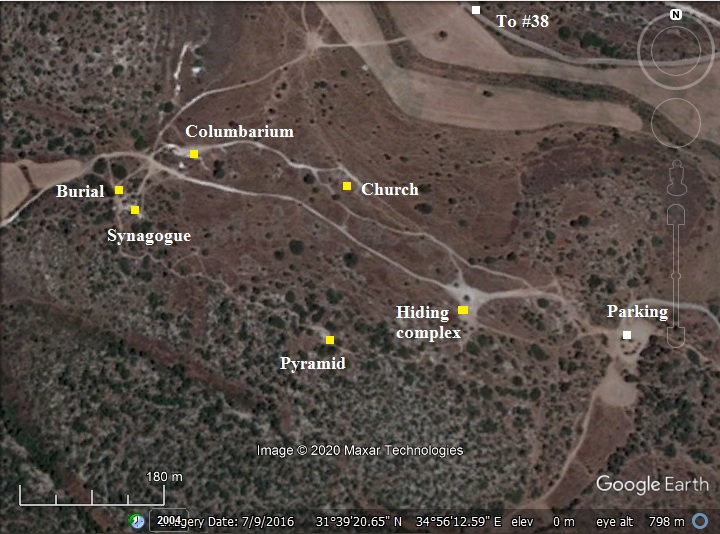

The following aerial view shows the area of the ruins of Horvat Midras, with the major points of interest marked as yellow squares. The site is situated on the northern slopes of a spur. The ruins cover an area of 250 dunams (25 hectares) – one of the largest rural settlements of the second temple period in Judea.

Access to the site is from Highway #38 from a park road that starts near Moshav Tsafririm. Follow signs to Horvat Midras.

History:

- Persian/Hellenistic period

The Jewish village was founded in the Persian or Early Hellenistic periods. It grew during the Hellenistic period.

- Early Roman period

The village reached its zenith during the Early and Middle Roman periods.

During the great revolt the village may have been damaged, but after this revolt, the village continued to prosper.

An Egyptian Geographer, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria, wrote in his World map book at ~150 AD about sites in the Levant. He mentions Drusis as a village in Judea.

- Hiding complexes

During the Bar Kokhba revolt, Jewish residents across most of the villages in Judea tried to save themselves by constructing underground hiding places. The Roman historian Cassius Dius wrote about this (Historia Romania, 69, 12, 3):

“To be sure, they did not dare try conclusions with the p449 Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved under ground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light”.

- Devastation of Judea

These hiding places may have saved some of the souls. However, the carnage that followed the onslaught left the village in ruins.

After its destruction, the Jewish population ceased, as all other Jewish villages in northern Judea. Cassius Dio, the historian of Rome, wrote about the devastation of Judea by Hadrian (Roman History, 69 13):

“Fifty of their most important outposts and nine hundred and eighty-five of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. Five hundred and eighty thousand men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out. Thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate, a result of which the people had had forewarning before the war”.

Head of Hadrian, found in the tombs of the Kings (PEF Jerusalem P. 406)

After 136 AD, Jews were forbidden to return to all settlements in the vicinity of Jerusalem. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote about this ban in the 4th century (Church History, Book IV, Ch. 6, 3):

“…the whole nation was prohibited from this time on by a decree, and by the commands of Hadrian, from ever going up to the country about Jerusalem. For the emperor gave orders that they should not even see from a distance the land of their fathers..”.

- Byzantine period

A small Christian community existed in the site during the 5th-6th century AD. Ruins of a grand church were excavated on the northern side. This was a small village, probably an assembly of monks. Some of the burial tombs have crosses engraved on the walls.

- Abbasid caliphate

The church was destroyed by the great earthquake of 749 AD.

Following the destruction of the church, the ruins of the building was reused by the Arabs.

During the middle ages there was limited agriculture activity at the site of the church.

- Ottoman period – PEF survey and excavations (19th Century AD)

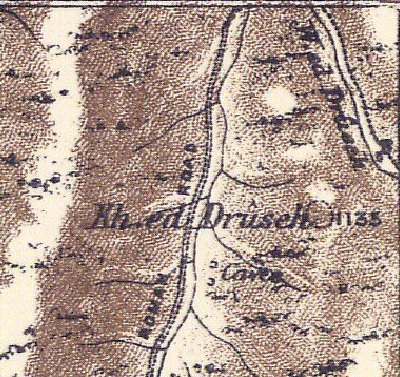

The area around the site was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their map is shown below, with the site in the center appearing as Kh. ed Druseh. The area around the site was heavily populated with farms and villages.

A major Roman road passes near the site, marked by double dashed lines. It connected the main road to Jerusalem in the valley of Elah to Beit Guvrin (Jibrin) on the south, and beyond to Ashkelon and Gaza. A number of Roman milestones were found nearby. This section appears on the Peutinger map, a medieval map which was based on a 4th century Roman military road map. Modern highway #38 actually traverses the same ancient route, just 800m west of Horvat Midras.

The PEF survey team merely wrote (Volume III, volume XX, p. 280):

“Khurbet ed Druseh (J u).—Heaps of stones, foundations.A ruined birkeh, and several caves.”.

The surveyors translated the name of the site – Kh. Druseh – as the “The ruin of the obliterated paths”.

Part of Map Sheet 20 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

-

Modern Period

Excavations of the church were conducted in the years 2010-11, headed by Amir Ganor (IAA) and A. Klein, after illicit digging at the site. The site was a focus of a new series of excavations in 2015-2019 by the Hebrew University, headed by Dr. Orit Peleg-Barkat.

Photos:

(a) Aerial Views

An aerial view of Horvat Midras was captured by the drone in 2018, looking towards the north and focusing on the central and western side of the village. The ruins are located along the slopes of the hill and in the plain north of it.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

(b) Foothills

A trail leads from from the parking place, located on the eastern side of Kh. Midras, to the ruins.

The path splits after 100m, where you can decide which path to take: a clockwise path around the site by first ascending to the eastern edge, or a counter clockwise path – continuing along the foothills. we selected the latter.

Along the foothills are scattered traces of structures. Only a few places were excavated so far in this large rural village, and so most of the ruins are still buried or partially exposed.

(c) Church

On an area along the path are remains of a Byzantine Church. This area view shows the area of the church, which was excavated in 2010-2011. The archaeologists unearthed beautiful colored mosaic floors in the whole area of the church.

In 2011 the floor was vandalized, so the site was covered in order to protect it.

Uncle Amnon is seen standing in this aerial view near the apse of the Church. It included an apse, a nave (5.3m x 10.6m), two aisles, and two L shaped rooms near the apse.

The apse of the church is seen better in the ground view below.

The archaeologists identified 7 phases of construction at this location:

- Phase 1 were walls and cavities dated to the Early Roman period.

- Phase 2 included a hiding place during the time between the Great Revolt and the Bar Kokhba revolt.

- Phase 3 included a burial cave, and a basilica structure which may have been built above and in conjunction with the burial cave.

- In phase 4 a church was constructed inside the earlier basilica structure, starting from the 3rd quarter of the 6th century AD, and ending in a natural destruction by the massive earthquake of 749 AD.

- The ruins were reused in the Abbasid period (phase 5), followed by agriculture use during the Mameluke and Ottoman periods (6,7).

Although the mosaic floor of the exposed Church was covered, several large carved stones were left above ground. This one is a massive carved lintel that belonged to a public building.

A hewn underground complex was located near the lintel.

A stone pillar lies here, decorated by a cross.

Another stone as a Greek letter “P” (R), here below. There were four massive fallen pillars found in the southwestern aisle. They were decorated with a Christogram, consisting of a cross with a loop at the top. The pillars together constituted the monogram of the Greek letters XP, Chi-Rho, means: Christ – the 1st 2 letters of Christos in Greek.

Since the basilica, and the church that was later constructed inside it, were built above the burial cave, some scholars (U. Dahari and L. Di Segni) suggested it belonged to the memorial complex of the tomb of prophet Zechariah.

(d) Columbarium

More than 50 underground complexes were documented in Midras, used for various purposes: water reservoirs, agricultural uses, storage and hiding complexes.

One of several agricultural underground cavities was a large Columbarium, which is located on the north west hillside.

Columbarium caves are common in Judea. The installation was used to grow pigeons and doves.

The entrance to the cave is thru this opening.

Inside this cave are dozens of pigeon niches. Their average depth is 15-25cm.

The word ‘columbarium’ is based on the Latin word columba (‘pigeon’), as it was originally used for a place to house doves and pigeons.

The agriculture use of the birds was for their meat, while the bird droppings were used as a fertilizer for growing food. The birds may have also served for ritual sacrifices.

A drone view of the columbarium can be seen in BibleWalks YouTube channel.

(e) Monumental Burial cave

The necropolis of Horvat Midras are on its west and south sides, and on hills surrounding the village.

One of the most magnificent burial caves is shown here. The walls on both sides leading to the entrance were covered by layer of plaster and painted with a red (fresco).

A large rolling stone (1.8m in diameter) used to seal the entrance to the burial cave. It rolls between two built walls.

The interior walls of the cave are paved with hewn stones.

Inside the cave are 6 burial chambers (“Kuchim”, or “burial recesses”), 1.80m in length. These stone benches held the corpses until the next burial of a member of the family who owned the cave. The custom of family-owned caves was common, and the Bible told about the practice in several verses: (Judges 8 32): “And Gideon the son of Joash died in a good old age, and was buried in the sepulchre of Joash his father”; (2 Samuel 2:32): “And they took up Asahel, and buried him in the sepulchre of his father, which was in Bethlehem”; (2 Samuel 17 23): “and died, and was buried in the sepulchre of his father.”.

This practice of using a “cold bed” was termed in the Bible as “gathered to his people”. Examples: (Genesis 25 8): “Abraham … died in a good old age, an old man, and full of years; and was gathered to his people”; (Genesis 49 33): “Jacob had made an end of commanding his sons, he gathered up his feet into the bed, and yielded up the ghost, and was gathered unto his people”.

Another chamber was an Arcosolium room, where burial coffins were stored. This was the 2nd phase of the burial. The bones of the decomposed body would be collected into the coffin – an ossuary – made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains. Ossuaries were a burial practice solely used by Jews, introduced at the end of the 1st century BC.

An arcosolium, plural arcosolia, is an arched recess used as a place of storing burial coffins. The word is from Latin arcus (“arch”), and solium (“throne”). There are three arcosolia.

The burial cave was constructed at the end of the 1st century AD, and was in use until the Bar Kokhbah revolt.

Other burial caves on this western edge of the village had a similar plan of two rooms in series – burial recesses (kuchim) and arcsolia.

15m south east of the monumental cave is another cave, dated to the 6th century AD. It has a smaller rolling stone (0.85 in diameter) and 3 arcsolia, with 16 engraved crosses painted red. That cave was connected to the monumental cave thru an underground tunnel, probably intended to serve as a hiding place.

(f) Synagogue

A well built ashlar structure was excavated on the west side of the hill, near the burial cave. This aerial view is towards the east.

The excavation exposed a large podium, 18.24m wide, built with massive walls on top of the bedrock.

A monumental staircase ascended to the podium from the west side.

The public structure, a synagogue, was constructed in the second century. This was dated according to the coins found in the excavation.

(g) Pyramid

Another point of interest is a funerary memorial structure, built on the south side of the village, on the topmost place of the hill. It is built close to a burial cave that is located on the foothill just below the structure.

The stepped structure, 10 by 10m, has a form of a pyramid. Its current height is 3m. The original height may have been 5m, as 3 levels are missing.

Father Yoram sits on one of the steps of the pyramid.

The use of a pyramid is rare in Israel. Another possible Pyramid was found nearby in Khirbet er-Rasm.

An aerial view of the Pyramid is available in BibleWalks youtube channel.

Another interesting stone is found nearby. This is a crushing stone of an oil press.

(h) Burial cave 2

An opening to another burial cave is nearby.

Inside – a set of burial chambers.

(i) Columbarium 2

Another columbarium is located nearby.

On the walls are pigeon niches.

Another section of the cave is a large bell shaped room. On its ceiling is an opening. This was originally a cistern used for storing water, and at later stage the cistern was converted to a columbarium.

A hiding tunnel was cut into the complex.

(j) Hiding complexes

In Horvat Midras are 10 documented underground hiding complexes, constructed to serve as refuge places during the Bar Kokhba revolt. These were cut into the soft rock, utilizing existing cisterns and underground storage places.

Another entry to this complex is located under a fig tree.

Stairs lead down to the “crawling” cave.

This was an originally a cistern used as a reservoir, and during the Bar Kokhba revolt was converted to a hiding place.

The tunnels were cut into the rock in order to crawl to the hidden chambers where the residents were to flee and stay for a length of time.

The tunnels were intentionally designed to be narrow and have crooked angles, make the crawling more difficult. Along the tunnels were places intended to block the passage. These were planned to deter the entry of the Roman soldier.

Conversely, in modern times the tunnels serve a completely different purpose. Families and kids love to come here to explore the tunnels and caves, and have fun.

From all the amazing findings in Horvat Midras, exploring the underground hiding places are the highlight of Horvat Midras.

(f) Video

![]() Fly over the site with this YouTube video.

Fly over the site with this YouTube video.

The drone video shows the major sites in Horvat Midras, starting from the Pyramid (a unique structure in Israel), then the synagogue (Roman period), followed by the Byzantine church, then the Columbarium.

Etymology:

Names of the site:

- Khirbat Durusiya – Arabic name of the site, perhaps preserved the Greek name

- Drus – Greek – indicates oak and terebinth (Elah) trees (Suggested by G. Steibel).

- Drusus – Roman – another suggestion of the origin of the name: a Herodian naming honoring Augustus’s adapted son who tragically died in 9 BC (as per Ziso/Kloner).

- Horvat Midras– Modern Hebrew name, based on the Arabic name Durusiya.

Links:

* Archaeology:

- Horvat Midras excavations – Hebrew University web page; based on research study: “Continuity and Change in Rural Judaea in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods: The Case of Horvat Midras”

- Horvat Midras (Kh. Durusiya): A Reassessment of an Archaeological Site from the Second Temple Period and the Bar-Kokhba Revolt- Boaz Zissu and Amos Kloner (pdf; 2010)

- Horvat Midras – Preliminary report HESI V124 2012

-

Church unearthed in Israel may hold Zechariah tomb

- Rock-Cut Hiding Complexes from the Roman Period in Israel Boaz Zissu and Amos Kloner (2009)

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- Boaz Zissu academic papers

* Internal – sites nearby:

- Valley of Elah – overview

- Adullam

- Horvat Ethri and Lavnin– adjacent villages

* Other:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- BibleWalks Youtube channel

- Greek initials

- Columbariums – installations

- Hiding Complexes info page

BibleWalks.com – travel with the Bible in hand

Horvat Rebbo<<<—previous site–<<< All Sites >>>—>>> —Next Judea site—>>> Abu Ghosh

This page was last updated on Mar 21, 2023 (new overview)