Horvat Nurit (Kh. Nuris) is a multi-period archaeological ruin, situated on the northern foothills of Mt. Gilboa.

Home > Sites > Mt. Gilboa > Horvat Nurit (Kh. Nuris)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Overview

* Ein Nurit

* Nuris ruins

* East side

* South caves

* West Hill

* Field survey

Links

Etymology

Background:

Horvat Nurit (Kh. Nuris), an archaeological ruin on the northern foothills of Mt. Gilboa, was inhabited from the Bronze Age up to 1948. The site includes ruins of an Ottoman period town, remains of earlier structures, quarries, caves, burials and agriculture installations in the surrounding area. Nurit spring served as the settlement’s primary water source.

Location:

The ruins of ancient Nurit are in an open public area. The ancient site is spread over the area seen in this aerial map. The modern community, Nurit, is built on the west side. The cross Gilboa road (#667) passes above the site. The eastern edge, where many ancient rock hewn installations are found, are now in danger due to the expanding modern quarry.

History:

-

Bronze and Iron Age periods

Nurit was populated from the Middle Bronze period I, a settlement that centered around the small spring. Around this small settlement were larger sites:

- Mt. Saul – Fortresses and buildings dating from the Bronze, Iron, Persian and Byzantine periods.

- Horvat Karemet (Giv’at Yehonathan) – First settled in the Chalcolithic period, a fortified city dated to the Bronze to the Iron Age II, protected by a large 3m high stone wall. Zori proposed that the city was the camp of the Biblical judge Gideon – ‘Ein Harod. Its settlement continued to the Roman period. The settlement moved to the site of Nurit.

- Tel Yizreel (Jezreel, Esdraelon) – the largest site in the area, 4km north west to Nurit

N. Zori dated ceramics in Nurit to the Early Bronze IV, Middle Bronze I, Iron age I and II, as well as later periods.

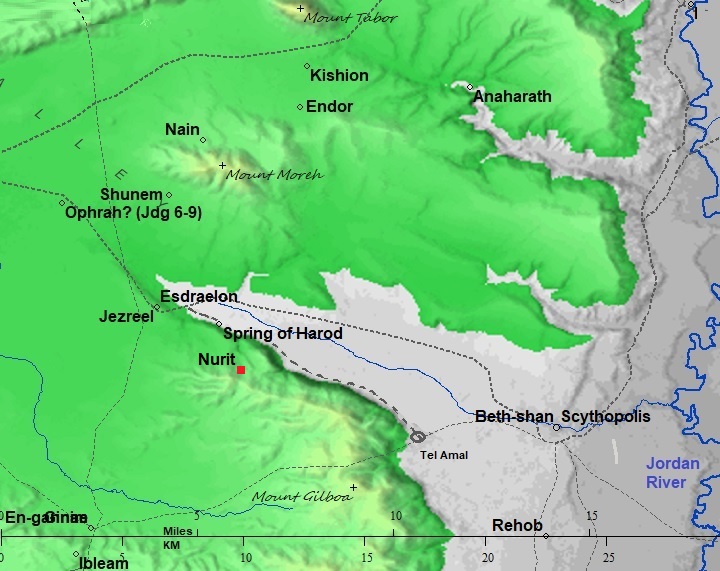

A Biblical map shows the location of the site, at the northern foothills of Mt. Gilboa, above the valley of Harod.

Map of the area around the site – from Canaanite/ Israelite to Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

- Roman/Byzantine period (63 BC- 634 AD)

As the result of the destruction of the Northern Israelite Kingdom, the fortified Tell on Horvat Karemet (Giv’at Yehonathan) was destroyed and abandoned. The new site relocated to the site of Nurit south west of the old Bronze/Iron age city. It became a farming village, centered around the spring and along the valley that descends to the Harod valley. The villagers were also engaged in stone quarrying.

The Late Roman and Byzantine periods were the primary settlement period in ancient Nurit. N. Zori found structural, pottery and glassware remains dated to the 3rd to the 6th century. His findings included an intact marble column and pedestal, lintels and columns.

On the east side of the village he found hewn cisterns, bases of houses, wine press, rectangular hewn tombs and arcsolia (arched recess used as a place of entombment). The majority of the findings was ceramics and glassware dated to the Roman and Byzantine period.

On the west side of the village he noted remains of ancient structures, with columns and bases of this period.

Nurit was probably a Jewish village, as attested by the existence of a hiding complex related to the Jewish revolts against the Romans. However, its synagogue was not yet found.

- Crusaders (1099-1291)

According to Zori, Nurit was one of the villages in the Harod valley that belonged to the Crusader monastery on Mount Tabor. In a Crusader accord (Pasxalis II, 1103) the name of the village is mentioned as Nurith.

-

Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

The village was in ruins until the mid 19th century.

According to N. Zori, several families came to settle it from Damascus and Beirut during the ruling period of general Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt. He conquered Ottoman Syria and the Holy Land in 1832 and governed the land until 1848.

The peasants in Nuris were tenant farmers under Sursuq – an Ottoman land owner and tax collector. Sursuq later sold sections of the lands of Nuris to the Jewish KKL agency following 40 years of negotiations.

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their survey map below shows the Northern area of Mt. Gilboa. The village is named Nuris, with a Sheikh tomb (Sh. Nimas) on its north east side. Mt. Saul appears here with its Arabic name – Jebel el Kaleily, meaning: the mountain with the peaks.

Part of Map sheet 9 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Arab villages existed at that time around Mt. Saul (Jebel el Kaleily): Nuris to the west, er-Rihaniyeh to the east, and el Mazar to the south west (see map above). The PEF report described the village of Nuris (SWP Volume 2, p. 86):

“Nuris – A small village on rocky ground, much hidden between the hills. It is situate above the steeper slopes of the Gilboa chain, which face northwards and below the main ridge, and is about 600 feet above the valley.

Note that most of the Arab villages, including these villages around Nuris, were built above or near ancient sites:

- Nuris (site #26 in the Arch. survey of Israel) was populated from the Middle Bronze I period through the Byzantine period;

- El Mazar (site #34) was populated from the Chalcolithic period through the Byzantine period;

- El Rihaniyeh (site #29) was populated from the Upper Paleolithic period through the Byzantine period (the majority of the findings).

In 1864 the traveler H.B Tristram passed horseback via Nuris on the road from Yizreel [Zerin] to El Mazar [Wezar], and reported (p. 504):

“At length, instead of doubling Gilboa by Zerin, we found a steep path which led us up by the village of Nuris to the Dervish colony of Wezar on its highest peak. Storks in thousands had settled for the night on the hill, resting during their northward migration, and from fatigue, or confidence in man, scarcely troubled themselves to fly off as we passed. Here we had a magnificent view over the plain of Esdraelon, tlhough not comprising any features not previously observed from other points. The path from Nuris to Wezar is most precipitous, scarcely practicable for horses ; and the inhabitants are exclusively Dervishes, who seem to have taken pos-session of the place, which is said to have formerly been deserted”.

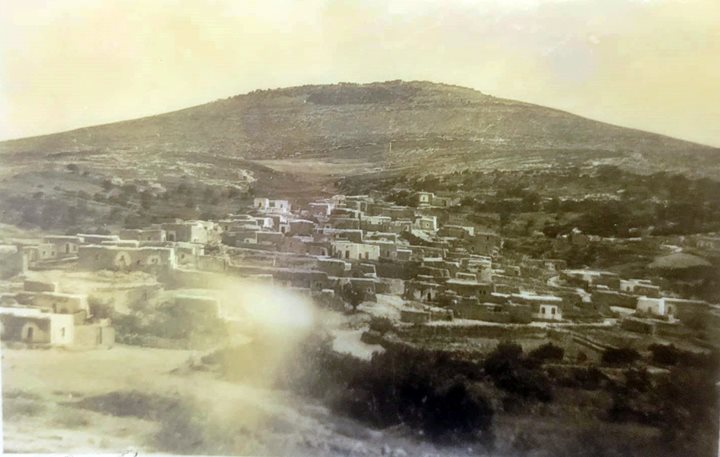

An old photo of the village of Nuris shows the houses and mount Wezar (Mezarim) in the background.

Photo courtesy Sturman museum, A. Keidar

- British Mandate

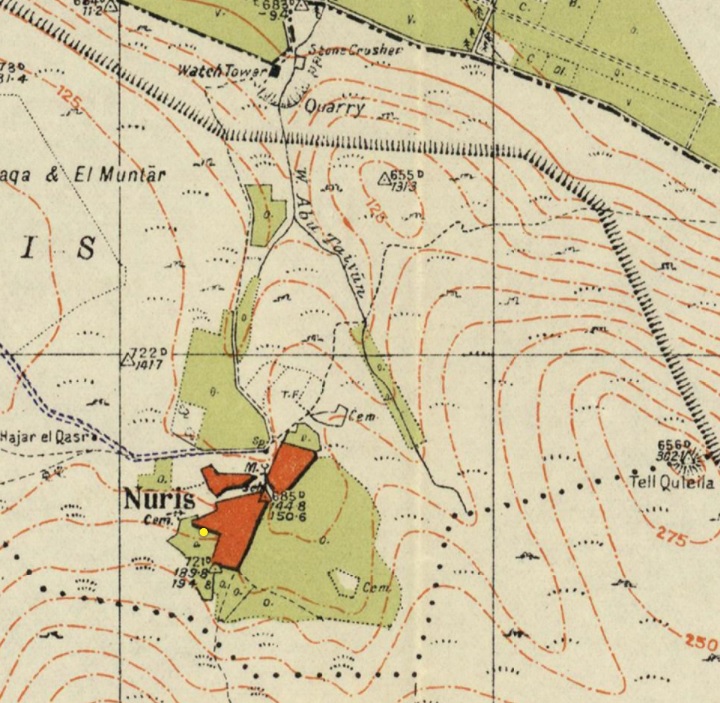

A section of the British map of the 1940s is shown here. The village (Nuris) covers the area south of the spring (marked by “Sp”). Mt. Saul is marked as Tell Quleila (Arabic: Jebel el Kaleily) on the east side. The access road to the village is from the west side, passing a point named Hajar el Qasr (Arabic: the stone fortress), a structure that is now in ruins.

The quarry in this map is limited to the lower foothills. Since then, the quarry grew in size and is now cutting away the eastern side of the ancient site.

https://palopenmaps.org – Palestine 1940s 1:20,000 map

Three cemeteries are marked “Cem” on the map around Nuris – on the north east, south east and the west sides.

During the Independence war, terrorist gangs operating in the village attacked nearby settlements. On March 19, 1948, soldiers of the nearby Jewish Kibbutz settlements conducted a failed attack on Nuris, sustaining 7 casualties. A memorial to the fallen 7 was erected on nearby Giv’at Yonathan.

In May 1948 Nuris was captured by the Israeli army. The village was abandoned and destroyed.

-

Modern Times

In 1950 new Yemenite settlers established the community of Nurit on the north side. However, they left after 9 years. A Nahal infantry brigade settlement replaced them in years 1959-1961, naming their settlement as Moshav Ram-On. In 1962 it was converted to a Gadna (Youth military program) camp, continuing until 1994. After several attempts to resettle the place, an ecovillage of Nurit was established in 2015 on the land north west of the ancient village.

There were several surveys of the site: N. Zori (Nurit/Nuris, published 1954 and 1977); Quarry area surveys ( 1994: Danny Sion; 2006: directed by Y. Tepper; 2017: directed by Y. Shalev); Kohn-Tavor A. 2013 salvage excavation along Nahal Yonathan (Wadi Ridan). A new survey is now conducted as part of the new archaeological survey of Mt. Gilboa, as part of the Manasseh Hill Country Survey.

Photos:

(a) Overview

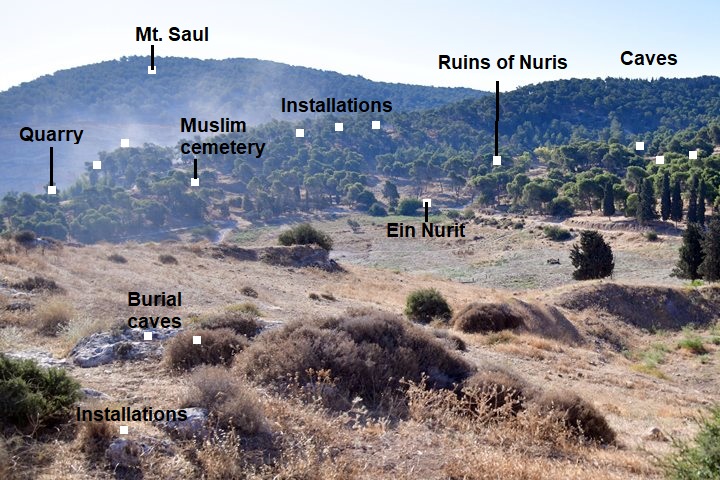

A view of the area around the ruins of Nurit was captured from the west side. The ancient site was built on the foothills of Mt. Gilboa, spread around a valley that descends to the Harod valley, reaching a point 0.7km east of Harod spring.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The major points of interest are marked on this view towards the east. The spring (Ein Nurit) is on the north side of the ruined village of Nuris. To the east is a large modern quarry, a Muslim cemetery and ancient tombs, agriculture installations, and bases of structures. On the foothills south of the spring are ruins of Muslim Nuris.

(b) Ein Nurit

Nurit spring is located on the north side of the ruined town, supplying water to the village and watering the fields around it. This tiny spring used to provide 50-70 cubic meters per hour (as per N. Zuri, 1954), but now its dried up.

During ancient times this spring was an important factor that supported the settlement and its crops. Very few springs and farming areas are found on top of Mt. Gilboa, while most of the springs are found on the valleys around the Gilboa. The Bible quoted a curse by King David who mourned the death of King Saul and his sons in the battle with the Philistines on Mt. Gilboa (2 Samuel 1:21): “Ye mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew, neither let there be rain, upon you, nor fields of offerings”.

The spring was in use until modern periods with this pump house.

A large mulberry tree (Tut) grows near the spring, feeding on the spring waters.

(c) Ruins of Nuris

Ruins of the Ottoman period village are scattered on the foothills south of the spring. Most of the area is covered by pine and oak trees, making it difficult to see under the leaves the ancient structures of the village and previous historic settlements.

Some remains of the village houses are seen today. According to Palestine Remembered website, there were 160 houses in 1948 before they were demolished.

(d) Muslim cemetery

Three Muslim cemeteries are located around the ruins of the village.

The major cemetery is on the north east side, close to the stone quarry. Two of the cemetery tombs are seen here. The PEF map shows that a Sheikh tomb, named Nimas, was buried here.

(e) East side installations

On the east side of the site, along the Harod quarry area, are a number of impressive rock-hewn installation complexes. They were investigated during a salvage survey and excavation prior to expanding the area of the quarry. The survey found along the west side of the quarry 27 cave openings (mostly blocked and sealed), 8 cist graves, a field tower, a dozen quarrying sites, and two winepresses. There were no remains of residential buildings in this area.

Here are some of the findings of the survey:

- Winepress installations

The survey around the quarry identified several winepresses, dated to the Late Roman and Byzantine periods. The winepress installations were exposed on the bedrock terraces. At a later phase the area transformed from wine production to olive oil industry, grain milling, stone quarrying and burial.

- Winepress 1

The first winepress, a simple installation cut on the top of a small rock surface, was numbered 1 and includes a large treading floor (quadrangular shaped, 2 x 2.5m) and an irregular collecting vat on its north side.

- Winepress 2

Another simple winepress complex has a small and shallow treading floor (elliptical shaped, 0.8 x 1.5m) with a deep collecting vat (quadrangular, 0.8m x 1.2m x 1.5m). This is seen in the following photo, with a view towards the north. In the center of the treading floor is a large and deep cupmark, probably cut after the winepress function was changed.

Three square cavities (used to hold the roofing wooden beams) and two cupmarks are cut in the bedrock behind the vat. Some of these cuttings are seen on the following photo with a view towards the south.

On the southern edge of this complex is a crushing basin. The basin (2.4m diameter) has raised rims (0.35m). Its crushing stone was not found here and may have been reused and embedded into a later settlement period, or hauled away. This device was operated by hand, probably used as a small oil press. It could also have been used for other crushing purposes such as for crushing grain into flour (such as barley, buckwheat, or other grains) or for grinding chalk rocks (for producing cement or lime and plaster).

At a later stage a stone quarry was cut into the rock around this complex.

- Winepress 3:

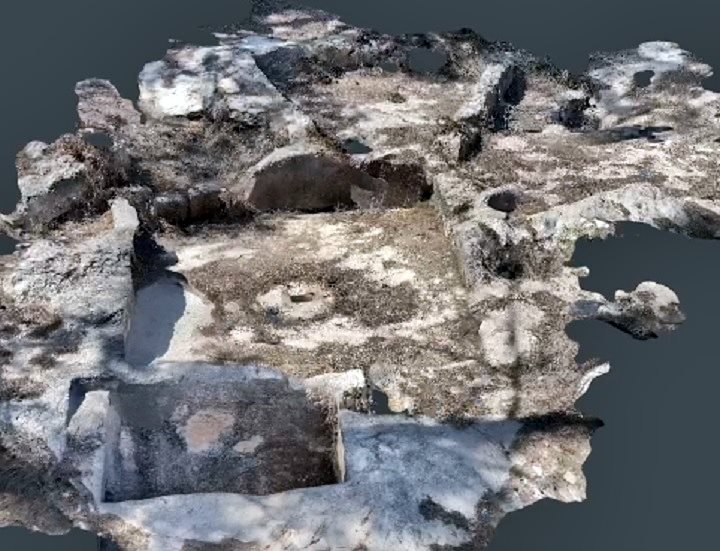

This larger industrial-level winepress complex is hewn into the rock on 3 inclining levels. It incudes a central treading floor, a collecting vat, a settling pit and two secondary floors. Its plan is similar to the type termed by Frankel/Ayalon as “Four Squares Plan”, common in the Byzantine period.

The central treading floor (square, 3.7m x 3.7m) was paved with white mosaic stones.

The treading floor is a large area, normally covered by mosaics, where the grapes are laid and crushed by the feet of the workers, extracting the juice. The juice, together with the crushed grapes, were left for preliminary fermentation (as suggested by Yeshu Drey). Use of shoes was avoided in order to prevent crushing the grape seeds, thus making the wine bitter.

A round stone with a square hole is perforated in the center, probably for holding a single fixed-screw press for secondary crushing of the grapes. The press squeezed out the must left in the grape skins and stalks after treading.

Above the central treading floor were two secondary treading floors (triangular in shape). They are seen below, rock cut on the west side of the central floor where Amnon is sitting. On the lower side of both floors is a deep circular basin (0.55m-0.65m in diameter, 0.35m deep). In the center of the right floor is a small cupmark, and another cupmark was cut into the left floor. Both floors did not have a mosaic paving as in the central floor.

A round settling pit (circular, 0.65 in diameter, 0.67m deep) was cut on the eastern wall of the central treading floor. It was paved with white mosaic stones.

The filter hole connecting the treading floor to the pit was first used to block the juice during the initial fermentation process on the floor. Then, used to let only the juice flow through, while the grape shell and pits remain in the treading floor.

An outlet hole led from the round settling pit into a large and deep collecting vat (rectangular, 1.5m x 2.3m, 1.5m deep) on the east side of the central treading floor. The vat is where the juice is accumulated and undergo the secondary fermentation process.

Three hewn and plastered steps lead down to the bottom of the collecting vat, paved with white mosaic. The walls were coated with gray plaster, embedded with a thick layer of white plaster over fragments of Late Roman and Byzantine pottery.

The steps that lead to the bottom of the pool were used by the workers to collect the juice into jars, and clean the pool.

Ofer stands here inside the collecting vat, above a lower round basin that was used to clean the vat.

A 3D model of this winepress is seen below. Pressing on the following photo will open a mp4 video player. After it turns around, use the player to turn it.

3D model of the Nurit Winepress – scanned by Scaniverse

- Burial structures on the east side:

A large rock hewn cist grave was also found on a bedrock south of winepress 2. A cist grave is a small coffin like box, built with stones or cut into rock, holding the body of the dead. This grave is rectangular, 0.8m x 2.5m, 1m deep. Around the rim of the tomb is a wide frame for covering it with slabs.

Amnon sits here on top of a circular crushing basin with raised rims (2m in diameter, 0.35m high) belonging to an earlier hand rotated installation. A large cupmark (0.4m in diameter) is on the side of the tomb, belonging to that earlier installation.

- More findings on the east side

Another rock hewn tomb was found on the bedrock, several hundred meters east of the village.

N. Zori also found in this area bases of houses, hewn cisterns, wine press, rectangular hewn tombs and arcsolia (arched recess used as a place of entombment). The majority of the findings was ceramics and glassware dated to the Roman and Byzantine period. The findings also included pottery dated to Middle Bronze I and Iron Age I-II periods.

A grand limestone sarcophagus, depicting geometric rosettes , was also found in ancient Nurit. It is on display in the archaeological museum in Nir David. It is dated to the 2nd-5th century AD.

A sarcophagus (sarcophagi in plural) – in Greek – means “flesh eater”. It is a stone coffin, intended to be a multiple use box that contained the body of the deceased for the first phase. After the flesh decomposed the bones were removed to a smaller container or pit, allowing the next member in the family to be placed in the coffin.

Photo – courtesy of the archaeological museum in Gan Hashlosha, Nir David

(f) South caves

A large cave (10m x 10m) is seen on the south side of highway #677. Parts of the cave have fallen.

On the northern side of the road, on the foothills above the ruins of Nuris, are a number of caves.

According to Yenon Shivtiel who surveyed a large cave complex in Nurit, it was used as a hiding complex during the great revolt against the Romans, and perhaps later during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Inside one of the the larger caves:

(g) West hill installations

On a hill west of the ruins are a number of ancient structures and installations. It seems like this western section of Nurit is a vast industrial area that was constructed on the exposed bedrock during the Byzantine period.

The following are samples of what we saw on the hill.

The ruin seen below, the only base of a structure we found on the hill, was probably one of the structures that were part of the Muslim village of Nuris. On the British map it is named Hajar el Qasr (Arabic: the stone fortress).

Nearby is a collecting vat of a Byzantine period winepress. Behind it is a large treading floor where the grapes were smashed with bare feet, and the juice would pour via a filter to the vat.

Steps lead down to the bottom of the vat. Its floor is paved with white mosaics.

Watch a short video of this winepress.

Nearby is another treading floor of a winepress.

Yet another Byzantine period winepress:

A crushing basin is also hewn into the bedrock. This device was operated by hand or with an animal, used as a small oil press. It could also have been used for other crushing purposes such as for crushing grain into flour or for grinding chalk rocks.

There are also a number of burial installations, such as this cist grave with raised rims:

Another rock hewn cist grave on the right, without the slabs covering the tomb. On the left is what appears as a crushing base, probably cut into the rock at an earlier phase.

On the east edge of the hill are a number of caves, used for burial places.

One of the burial caves, with a buried arcsolia (arched recess used as a place of entombment):

(h) Nuris Field survey

This 11 minutes video was filmed during a survey of the Mt. Gilboa Archaeological Survey team, conducted on Dec 2024, and headed by archaeologists Shar Bar and Ayelet Keidar.

Links and references:

* Archaeological links:

- Arch. Survey of Israel (Hebrew, English)- Map #62 – Ein Harod – site #26 (Nuris, Nurit)

- Nuris, survey – Yotam Tepper, HAESI 121 2009 – survey around the quarry

- Gilboa mountains – N. Zuri, 1954

* Other links:

* Nearby sites:

- Saul’s Shoulder – Mt. Saul

- Yonathan Hill – nearby Bronze/Iron period walled city

- Harod spring – nearby attraction

- Tel Yizreel – nearby ruins of Israeli Kingdom palace

* Internal sites:

- Winepresses in the Holy Land

- Hiding complexes

- Mt. Gilboa archaeological survey

Etymology (behind the name):

- Gilboa – Biblical name of the mountain range. A possible source of the name is Gal-Nove’a (Hebrew for gushing-waves, named after its springs along the foothills).

- Saul – Hebrew: Sh’aul, comes from the Hebrew verb Sha’al (ask).

- Jebel el Kaleily – Arabic name of Mt. Saul, meaning: the mountain with the peaks (source: PEF dictionary, p. 161).

- Nurit – A moshav west of the site, first established in 1950. Named after the “buttercup” flower (a Ranunculus species). Hareuveni suggested a Biblical identification as “Nitzanim” (הַנִּצָּנִים) (Song of Solomon, 2:12): “The flowers appear on the earth…”.

- Nuris – Arabic: a private name, preserving the ancient name.

BibleWalks.com – exploring the ancient sites of Israel

Saul’s shoulder <<—previous site—<<< All Sites>>>— next Gilboa site —>>>Yonathan Hill

This page was last updated on Mar 28, 2025 (add old photo)

Sponsored links: