Ruins of multi-period archaeological site on the summit of a high hill of Mount Gilboa.

Home > Sites > Mt. Gilboa > Horvat Mazarim (Kh. al-Mazar, Har Giborim)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Overview

* Ascent

* Cisterns

* Summit

* Cemaics

* Southern foothills

* Western foothills

* West Hill

Links

Etymology

Background:

Ruins of Horvat Mazarim (Khirbet al-Mazar) are spread over the summit of a high hill (Har Giborim, altitude 412m) on the north west mountain range of Gilboa. A multi-period village existed here, starting from the Chalcolithic period until 1948.

Location:

The site is located on a summit on the western Gilboa, at an elevation of 412m. It is on public area. Two rough access roads reach the summit from the north and south.

History:

Chalcolithic period (4,500 – 3,150BC)

A multi-period village existed on the site, starting from the Chalcolithic period.

-

Bronze period

N. Zori dated ceramics in Horvat Mazarim to the Bronze period (except for the Middle Bronze I).

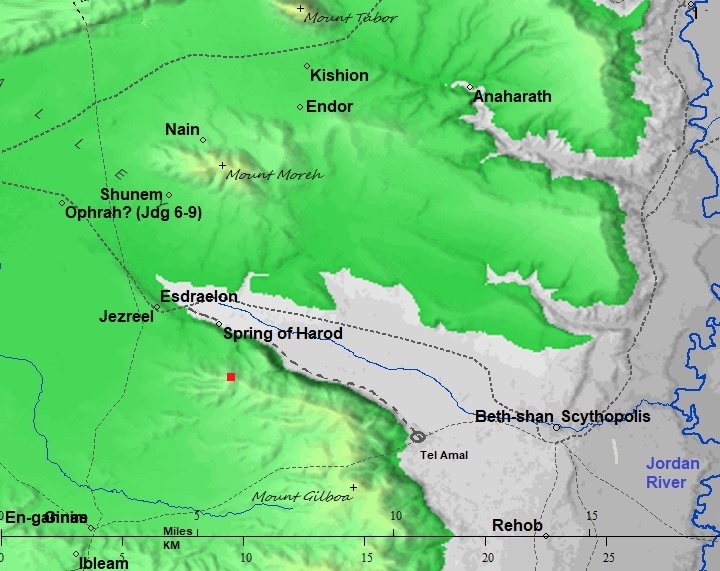

A Biblical map shows the location of the site, at the northern foothills of Mt. Gilboa, above the valley of Harod.

Map of the area around the site – from Canaanite/ Israelite to Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

- Iron Age I (1200-1000 BC)

This is the period of the Judges, a period in the Bible that refers to the time between the death of Joshua and the establishment of the monarchy in Israel, marked by the reign of Saul.

- Identification as Meroz

Meroz was a city that did not join the battle of Israel against the Canaanites, and was cursed by the prophetess and judge Deborah, during the time of the battle of Barak against Sisera (Judges 5:23):

“Curse ye Meroz, said the angel of the LORD, curse ye bitterly the inhabitants thereof; because they came not to the help of the LORD, to the help of the LORD against the mighty”.

This curse was part of Deborah and Barak’s victory song, which celebrated Israel’s triumph over the Canaanite forces led by Sisera. Meroz was likely a city or settlement near the battlefield where the tribes of Israel were fighting. Its inhabitants were expected to join or assist in the battle but chose not to. Their inaction was seen as a betrayal, especially during a time of great need when the survival of Israel depended on unity and courage.

Horvat Mazarim has been suggested as a possible location for the Biblical city of Meroz based on the following considerations: geographic (the village overlooks the battlefield area in the Jezreel valley), linguistic (Mazar sounds phonetically similar to Meroz), and historical (the village was inhabited during the time of the battle – Iron Age I).

Illustration of the battle between Barak and Sisera

(Image created by AI using DALL·E through OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

- Iron Age II (1000BC – 586 BC)

The site continued to be settled in this period.

As the result of the destruction of the Northern Israelite Kingdom, the site was destroyed and abandoned.

- Roman/Byzantine period (63 BC- 634 AD)

The site reached a peak during the Late Roman and Byzantine periods.

-

Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

The Arab village of el Mazar was named after the tomb (or shrine) of Neby Mazar that stood in the center of the village. During the Ottoman and British Mandate periods this secluded village up in the high mountains was a place of Muslim pilgrimage that attracted blind Muslims and Dervishes (members of a Sufi fraternity who chose or accepted material poverty). Mazar means a Muslim shrine or enshrined tomb. It is based on the Arabic word Zaara – visit – as the faithful come to visit and honor the holy man. The shrine commemorated Neby Mazar who was according to tradition as one of the descendants of Abraham.

Sufism:

Sufism, a mystical and spiritual tradition within Islam, has a historical and ongoing presence in the Holy Land. This region has been a crossroads of religious and cultural exchanges, making it a significant location for Sufi practices and teachings. Sufism likely entered the Holy Land during the early Islamic conquests in the 7th century. As the region was integrated into the broader Islamic world, Sufi practices and ideas were introduced by travelers, scholars, and mystics. Cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Nablus, Acre, and Gaza became important hubs for Sufi orders. The presence of significant Islamic sanctuaries, such as the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, further attracted Sufi activity.

Throughout the land, on hilltops or at the edge of towns, the Sufi shrines were built in lonely places. The Sufis were similar to the ascetic Christian hermits – they retreated to the hills or desert for solitary prayer and contemplation. The high mountain of el Mazar was a perfect seclusion place for Sufis.

The prominent Sufis were buried in their villages, and shrines were constructed to commemorated them. Sufism attracted many followers and pilgrims. The Sufis built lodges (khanqahs, zawiyas, or tekkes) to serve as centers for spiritual practice, learning, and community service.

The Sufi village of al-Mazar is a site of significant spiritual and historical importance in the Islamic and Sufi tradition. The village is closely associated with Neby Mazar, believed by local tradition to be the burial site of a prophet or revered figure, and has historically been a focal point for Sufi devotion. While little is definitively known about the historical identity of Neby Mazar, local traditions venerate the site as the resting place of a saint or prophet. Oral traditions among Palestinian communities link Nabi Mazar to miraculous stories, piety, or a connection to the divine. These narratives, often transmitted through generations, emphasize his spiritual significance. The shrine became a center for Sufi rituals, especially during annual festivals (muwasims).

Sufi Practices at al-Mazar:

Ziyara (Pilgrimage): Pilgrims would visit the site to offer prayers, seek blessings, and perform rituals of dhikr (remembrance of God). The practice of ziyara reflects the Sufi emphasis on connecting with the divine through veneration of saints and sacred places.

Annual Celebrations: Al-Mazar hosted annual gatherings, often coinciding with specific Islamic or agricultural calendars. These events were marked by communal prayers, dhikr, Sufi poetry (qasidas), and acts of charity.

Zawiyas and Sufi Communities: The village likely supported a zawiya (Sufi lodge) or similar structure where Sufi practitioners could reside and hold spiritual gatherings. Such lodges were integral to Sufi life, serving as places of teaching, retreat, and worship.

Muslim shrines:

According to article by Frantzman and Bar (2013), there were 682 (!) Sheikhs’ tombs in Palestine countryside, of which 71% were located on hill regions, with the average height of the shrines at 347m above sea level. Most shrines were constructed on high places with commanding views, such as Mazar. Most of the shrines were separated from settlements, and require a walk to the site.

They were built in a simple plan of one or two square rooms with a small dome covering them. In central pilgrimage destinations additional rooms were added to accommodate the visitors. Their thick walls, built to support the dome, were built of local stones and not plastered nor decorated. The door entrance was usually on the north side, and a mihrab (small prayer niche) on the south wall. Inside the middle of the room was a tomb, plastered white, oriented west-east and facing Mecca.

The history of sheikh tombs and the reason they were built is yet to be researched. Some of the tombs commemorated prophets (‘Neby’) that are mentioned in the Quran that are also known in the Bible. In many cases, such as Mazar, the village was named after the shrine but dropping the ‘Neby’. Other tombs commemorated other people, such as historic and religious Muslim figures and warriors, with a minority of which were women. In recent years most of the Sheikh tombs have been destroyed or been neglected, and their culture value in the Muslim population has greatly declined.

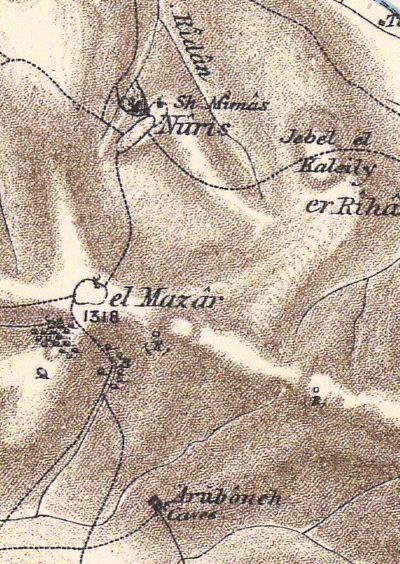

PEF survey:

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. A section of their survey map below shows the Northern area of Mt. Gilboa. The surveyors wrote about the place (Volume II, Sheet IX, p. 85):

“El Mazar, or El Wezr —A village on the summit of the mountain. It is principally built of stone, and has a well on the south-east. A few olives surround the houses. The site is very rocky. It is inhabited by Derwishes, and is a place of Moslem pilgrimage”.

Part of Map sheet 9 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Travelers:

In 1864 the traveler H.B Tristram passed horseback via Nuris on the road from Zerin (Arab village on Tel Yizreel) to El Mazar (Wezar), and reported (p. 504):

“At length, instead of doubling Gilboa by Zerin, we found a steep path which led us up by the village of Nuris to the Dervish colony of Wezar [Mazar] on its highest peak. Storks in thousands had settled for the night on the hill, resting during their northward migration, and from fatigue, or confidence in man, scarcely troubled themselves to fly off as we passed. Here we had a magnificent view over the plain of Esdraelon, although not comprising any features not previously observed from other points. The path from Nuris to Wezar [Mazar] is most precipitous, scarcely practicable for horses ; and the inhabitants are exclusively Dervishes, who seem to have taken possession of the place, which is said to have formerly been deserted”.

During the late Ottoman era and the British Mandate, al-Mazar remained a small village with a notable religious significance. However, political and social changes began to affect its status as a spiritual center.

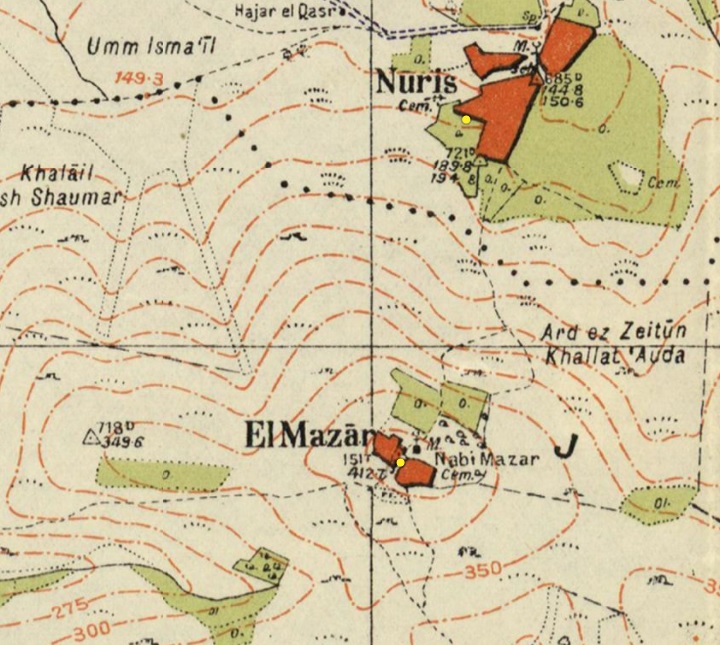

- British Mandate

A section of the British map of the 1940s is shown here. The village, El Mazar, was located on the summit south of the village of Nuris. Both villages were destroyed during the independence war.

https://palopenmaps.org – Palestine 1940s 1:20,000 map

Access roads are marked on the map as arriving from north (Nuris access), west (Jenin access) and south (Arraneh and Deir Ghuzzaleh). The shrine is marked in the center of the village. A cemetery is marked “Cem” on the map on the east side of the village.

During the Arab revolts in 1929 and 1936-1939 the village was a center of Arab gangs led by Sheikh Farhan al-Saadi, a Palestinian rebel commander and revolutionary, and a member of the gang of Sheikh Iz al Din al-Qassam. He was executed by the British in 1937.

- Independence war

During the Independence war, terrorist gangs operating in the village attacked nearby settlements. The place was a center for the forces of the Arab Liberation Army headed by Sheikh Fawzi al-Qawugi. During the battles, Qawugi’s forces attempted to haul a heavy canon from the Jenin valley along the western ascend along the valley of Nahal Gilboa.

In May 29, 1948 the villagers abandoned el-Mazar after the fall of Zerin. In the 1960s the village was totally demolished.

The hill is named in Hebrew “Har Giborim” – mountain of the Heroes. This name honors the fall of King Saul and his sons, and also the courageous soldiers who played a pivotal role in liberating the area from armed gangs and securing this strategic location in 1948.

-

Modern Times

N. Zori surveyed the site and published the findings in 1977. A new survey is now conducted as part of the new archaeological survey of Mt. Gilboa, as part of the Manasseh Hill Country Survey.

Photos:

(a) Overview

On the west side of Mount Gilboa are several mountain peaks. This photo, captured on the cross-Gilboa road (highway #667), is a view of the mountain peak named Har Giborim (mountain of the heroes). On the top of its peak is the multi-period archaeological site of Horvat Mazarim.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

(b) Ascent to the site

The summit is 300m above the highway. Ascent to the summit is along two dirt roads – one from the north and the other from the south. Both roads pose a challenge to 4×4 vehicles due to the extremely rough surface. Due to the condition of the road we had to leave the car at a lower height and walk up the steep ascent. Not an easy task! Even the 19th century Tristram wrote about this ascent: “…The path from Nuris to Wezar [Mazar] is most precipitous, scarcely practicable for horses “.

Another section of the long ascent road is seen below. The SUV almost stuck at this point due to the unsteady surface.

The height difference was one of the key defense advantages of the site. Another advantage was that the enemy could be spotted from all directions for long ranges. Its a strategic commanding position overlooking the area made it an important outpost.

On the summit point are remarkable views of the Jezreel valley on the north (as below), the Jenin (Ein Ganim) valley on the south, and the Jordan valley on the far east.

(c) Cisterns

On the summit and foothills are many hewn cisterns. Water supply was from these reservoirs and from ‘Ein Shaul spring, 200m south east of the summit.

Another opening of a cistern is in the next photo.

(d) Summit

On the summit are ruins of the houses, cisterns, installations, and olive trees.

A multi-period village existed here, starting from the Chalcolithic period until 1948. Traces of the structures and walls are seen across the summit and the foothills.

We tried to locate the ruin of the shrine of Neby Mazar. This Sufi shrine was in the center of the village, but we couldn’t find it. The domed structure was built in the 18th century, and its adjacent pool was used for ritual purification.

An aerial view of the summit is seen here from the south side. The ruins are spread across the top of the hill. The access road loops around the summit and then descends to the north. In the far background is the Jezreel valley.

![]() The drone captured this video of Horvat Mazarim:

The drone captured this video of Horvat Mazarim:

(d) Ceramic dating:

During our short survey we collected ceramics and flint stones in order to date the periods of settlements. We found both Bronze/Iron Age, Roman/Byzantine and Ottoman period pottery. The pottery was dated by archaeologist Ayelet Keidar and marked on the photo below.

According to N.Zori survey (1977 site #3), the ceramics were dated from all periods from the Chalcolithic to the Muslim period, but without the Middle Bronze I period. Zori also dated coins to the Byzantine period.

(e) Southern foothill

On the southern foothill are military trenches. We do not know when they were constructed.

Another section of the trenches along the south west side. Along the valley below, Nahal Gilboa, was an old road to Sandala, an Arab village the falls under the jurisdiction of Gilboa Regional Council. In the far background is the fertile valley of Jenin (Ein Ganim) – a gateway to the heart of Samaria.

On the foothill are ruins of structures, probably remains of the Arab village.

Another walled area built on the south west foothill:

(f) Western foothill

On the western foothill are agriculture installations and cisterns. Most of them were built during the Byzantine period.

This photo, captured toward the east, shows the western foothill of Har Giborim. Horvat Mazarim is on the top of the hill.

On the western side of the summit is an underground cavity, covered with long stone slabs. Ronnie stands over one of the covering slabs.

On the saddle between Mazarim and the west hill are remains of a cistern. A stone trough beside the cistern served as a drinking spot for the cattle.

A reverse view of the cistern and trough, as seen from the west side, is in the photo below.

Nearby is a treading floor of a winepress. Wine production was one of the main incomes in the region during the Roman/Byzantine period. Vineyards were planted across the Gilboa mountain in small lots.

Winepress installations were typically constructed near vineyards to streamline the wine production process. Proximity to the vineyards minimized the time and effort required to transport freshly harvested grapes to the pressing site, preserving the quality of the grapes by reducing the risk of spoilage.

(g) West Hill

Additional installations and watch towers are found on the top and foothill of the west hill, a ridge at an altitude of 364m.

- South side of the west hill:

From the south side of the hill are great views of the fertile valley of Jenin (Ein Ganim). During the ancient times a major route connected the Jizreel valley to the heart of Samaria.

Remains of a watch tower are seen here. It is built with large slabs. The purpose of this post may have been as a lookout point on the road that ascended from the Jenin valley along Nahal Gilboa.

Small square watch towers were also commonly constructed around the vineyards. As per the Bible (Isaiah 5: 1-2):

“Now will I sing to my wellbeloved a song of my beloved touching his vineyard. My well beloved hath a vineyard in a very fruitful hill: And he fenced it, and gathered out the stones thereof, and planted it with the choicest vine, and built a tower in the midst of it, and also made a winepress therein: and he looked that it should bring forth grapes, and it brought forth wild grapes”.

A closer view of the watch tower is below.

On the side of the watch tower are remains of a structure.

An engraved cross was spotted on one of the rocks.

- North side of the west hill:

Another watch tower is located on the other side of the hill – overlooking the Jezreel valley.

Below – another view of this watch tower.

We collected pottery fragments to date the installations. They were of the Iron Age (the handle with a hole), and the rest Bronze/Iron and Byzantine periods.

Another watch tower is located on the north east side of the west hill.

A treading floor of a winepress was also seen on the north east foothill of the west hill.

A crack in this Byzantine period winepress may have been a result of the 749 AD severe earthquake.

Links and references:

* Archaeological links:

- Arch. Survey of Israel (Hebrew, English)- Map #62 – Ein Harod – site #26 (Nuris, Nurit)

- Gilboa mountains – N. Zuri, 1954

* Nearby sites:

- Saul’s Shoulder – Mt. Saul

- Yonathan Hill – nearby Bronze/Iron period walled city

- Harod spring – nearby attraction

- Tel Yizreel – nearby ruins of Israeli Kingdom palace

* Internal sites:

- Winepresses in the Holy Land

- Mt. Gilboa archaeological survey

Etymology (behind the name):

- el Mazar – The name of the ruined Arab village. Mazar means a Muslim shrine or enshrined tomb. It is based on the Arabic word Zaara – visit – as the faithful come to visit and honor the holy man.

- Horvat Mazarim – the Hebrew name, based on the Arab name.

- Har Giborim – Another name of the site. Hebrew for: “Mountain of the Heroes”. This name honors Saul and his sons who died fighting the Philistines, and also the courageous soldiers who played a pivotal role in liberating the area from armed gangs and securing this strategic location in 1948.

- Gilboa – Biblical name of the mountain range. A possible source of the name is Gal-Nove’a (Hebrew for gushing-waves, named after its springs along the foothills).

- Sufi – Arabic term, meaning: Islamic mysticism. The village of el_mazar was a Sufi center.

- Dervish – from Persian, meaning: members of a Sufi Islam fraternity

BibleWalks.com – exploring the ancient sites of Israel

Yonathan Hill<<<—previous site—<<< All Sites>>>— next Gilboa site —>>>

This page was last updated on Dec 14, 2024 (info on Sheikhs tombs)

Sponsored links: