A spring, park and historic site on the foothills of Mt. Gilboa.

(Judges 7:1): “Gideon… pitched beside the well of Harod”.

Home > Sites > Yizreel Valley > Harod Spring (‘Ein Jalut or Jalud)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Gilboa

* The Park

* Spring

* Hankin tomb

* Monument

Links

Etymology

Background:

Harod Spring, or “Ein Harod” in Hebrew, is a spring and historic site located in northern Israel. The area has historical significance and has been mentioned in various contexts, such as mentioned in the Biblical account of Gideon and his troops drinking water from the spring in the process of narrowing down his troops.

Ein Harod is also associated with the Battle of Ain Jalut, which took place in 1260 AD between the Mamluk Empire and the Mongol Empire. This battle is significant because the Mamluks were able to halt the Mongol advance into the Middle East, which had far-reaching historical implications.

In addition to its historical importance, Ein Harod is a popular destination for tourists and visitors due to its natural beauty and the Ein Harod National Park that surrounds the spring. The park features hiking trails, archaeological sites, and stunning landscapes.

Location:

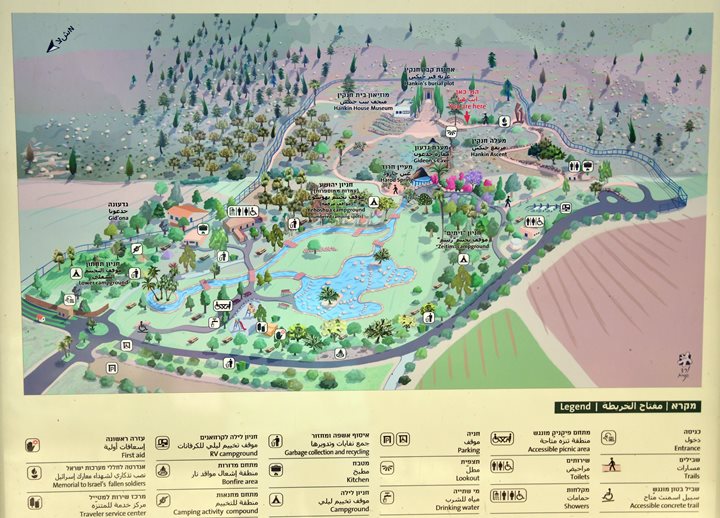

An aerial map of the site is shown here, focusing on the Ein Harod National Park and the spring. The parking lot is on the northern side of the park. The spring is at the foothill of Mt. Gilboa, and above it is the tomb and historic house of Hankin. Between the parking and the spring are pools and streams. On the east side of the park is Gidona – a community settlement named after the judge and leader Gideon.

History:

- Biblical period (Iron Age 1200-586 BC)

* Gideon selects his soldiers at the spring:

Gideon (also spelled as Gidon) is a prominent figure in the Bible, specifically in the Book of Judges in the Old Testament. He is known for his role as a judge and leader of the Israelites during a time of oppression by the Midianites. The story of Gideon is recounted in Judges chapters 6 through 8.

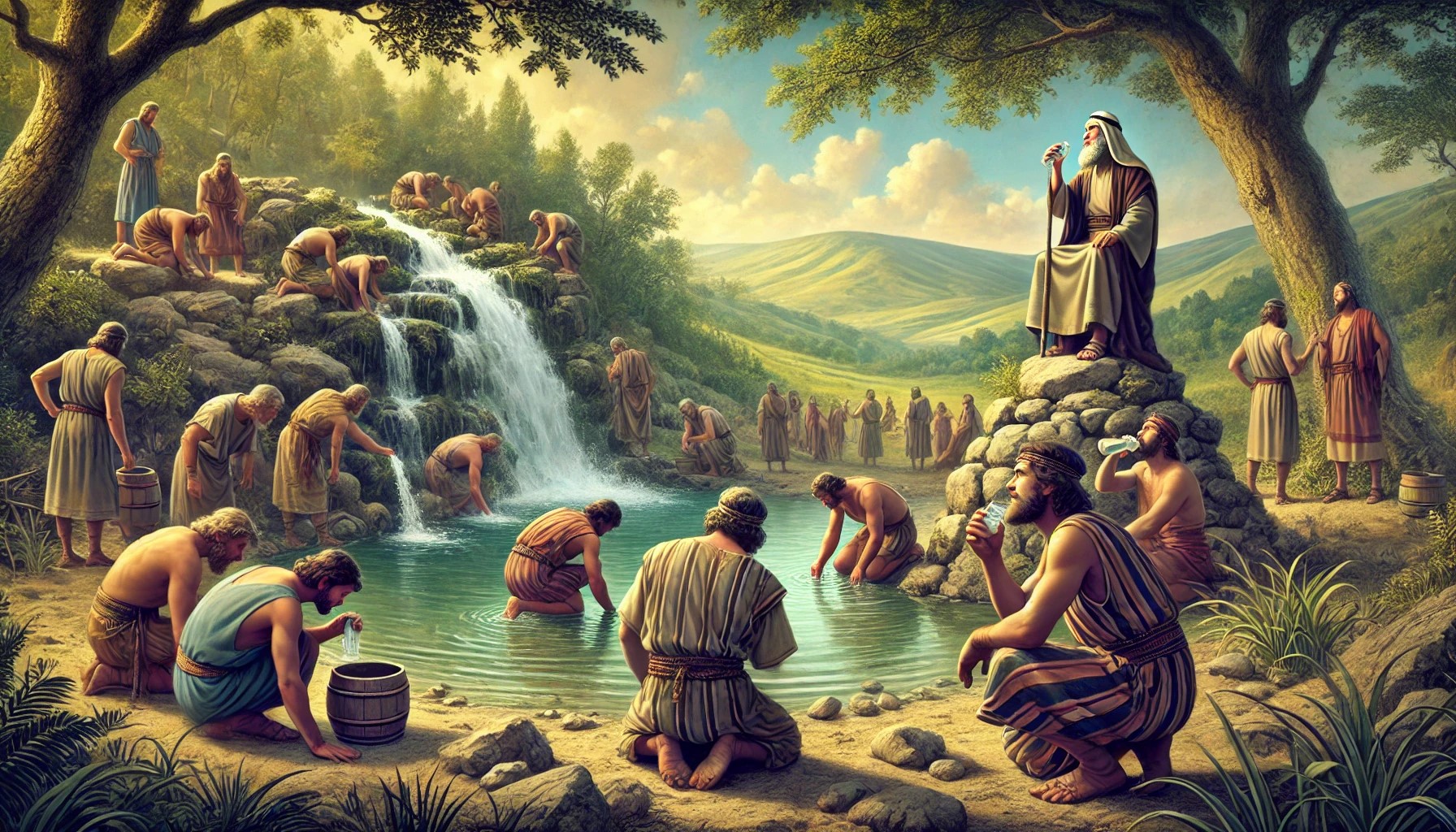

The connection between Gideon and the Spring of Harod (Ein Harod) comes from the Biblical account of Gideon’s selection of soldiers for battle against the Midianites. According to the narrative, Gideon gathered a large number of Israelite men to face the Midianite forces, which greatly outnumbered them. However, in a series of events, Gideon led a process of narrowing down his troops through a unique test involving the spring.

Judges 7:1, 4-7 describes this event:

“Then Jerubbaal, who is Gideon, and all the people that were with him, rose up early, and pitched beside the well of Harod: so that the host of the Midianites were on the north side of them, by the hill of Moreh, in the valley….

… And the LORD said unto Gideon, The people are yet too many; bring them down unto the water, and I will try them for thee there: and it shall be, that of whom I say unto thee, This shall go with thee, the same shall go with thee; and of whomsoever I say unto thee, This shall not go with thee, the same shall not go.

So he brought down the people unto the water: and the LORD said unto Gideon, Every one that lappeth of the water with his tongue, as a dog lappeth, him shalt thou set by himself; likewise every one that boweth down upon his knees to drink.

And the number of them that lapped, putting their hand to their mouth, were three hundred men: but all the rest of the people bowed down upon their knees to drink water.

And the LORD said unto Gideon, By the three hundred men that lapped will I save you, and deliver the Midianites into thine hand: and let all the other people go every man unto his place”.

Illustration of the selection of the 300 fighters at the spring of Herod.

(Image created by AI using DALL·E through OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

In this story, the spring of Harod (Ein Harod) is where Gideon brought troops to drink water. The men who drank water by lapping it like a dog were chosen to stay and fight, while the rest were sent home. The connection to the spring underscores a key moment in Gideon’s story, where his army was significantly reduced to a small but dedicated group. With this smaller force, Gideon went on to achieve a miraculous victory over the Midianites, demonstrating God’s intervention and guidance.

With this smaller force, Gideon went on to achieve a miraculous victory over the Midianites, demonstrating God’s intervention and guidance. In the middle of the night, Gideon’s 300 men surround the Midianite camp in the valley below. On Gideon’s signal, they break the clay jars, revealing the torches, blow their trumpets, and shout, “A sword for the Lord and for Gideon!”. The sudden noise, light, and confusion throw the Midianites into panic. Believing they are under attack by a much larger force, the Midianites turn on each other in the chaos and flee. Gideon and his men pursue the fleeing Midianites, securing a decisive victory.

Illustration of the Battle of Gideon and the Midianites, capturing the intense and dramatic scene of the nighttime battle.

(Image created by AI using DALL·E through OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

As a result, the Spring of Harod holds a significant place in the biblical account of Gideon’s story and symbolizes the divine selection of a chosen few for a challenging task.

* Goliath’s spring?

The name “Ain Jalut” is derived from Arabic. “Ain” means “spring” or “water source,” and “Jalut” (or “Jalud”) is the Arabic name for Goliath, the biblical figure known for his battle against the young David in the valley of Elah. The name “Ain Jalut” can be translated as “Spring of Goliath” or “Goliath’s Spring.”. It is unknown why this spring was named after Goliath, perhaps due to an early Christian tradition associating the valley to the place of battle with David, or to the resemblance of the name Gilboa to Jalud.

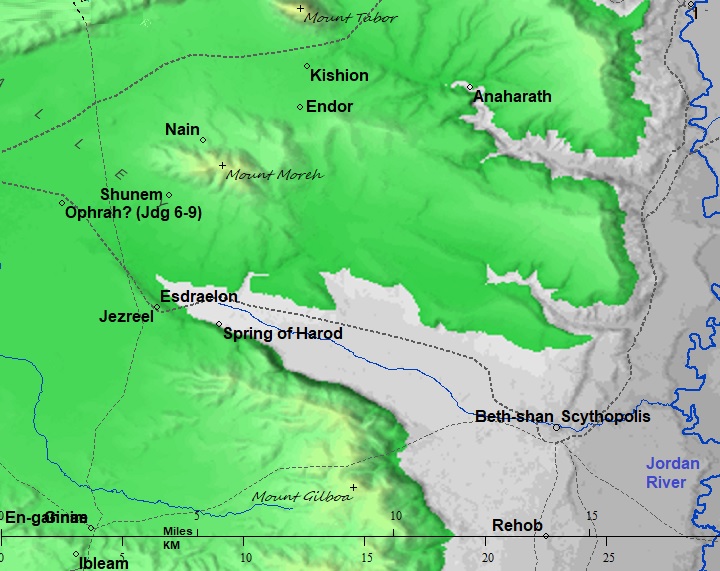

* Biblical map:

A Biblical map shows the location of the site, in the valley of Harod at the foot of Mt. Gilboa. The Harod valley is 11km long and 1-2 kilometers wide. The waters of the Harod spring, as well as waters from other springs at the foot of Mt. Gilboa, feed into the Harod river. The river actually starts from Mt. Moreh north of the spring, flows eastwards thru the valley towards Beit-Shean (Scythopolis), and joins the Jordan river – a total length of 35km.

Map of the area around the site – from Canaanite/ Israelite to Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

During antiquity the Harod river created swamps and marches along the valley. It was possible to cross the valley from the Jezreel Valley to Beit Shean only along the southern or northern edges of the valley. According to David Dorsey, basing on the chain of Iron age sites found along this route, the west-east highway (“T7”) passed on the southern side of the valley. One of the stations was the Harod spring. This changed in the Roman period, when the road passed along the northern edge.

- Crusaders/Ayyubid

The spring was captured by the Crusaders after their entry to the Holy Land in 1099. The ability to secure and control water sources was crucial for any ruling power in the arid landscapes of the Levant. Water determined the viability of settlements, agriculture, and the movement of armies. Harod spring is located on the strategic route descending to Beit Shean and the Jordan valley.

* Battle of al-Fule:

A battle occurred near the spring in September 1183. In the campaign known as the Battle of al-Fule (or La Fève/Castrum Fabe), a Crusader force led by Guy of Lusignan fought against Saladin’s Ayyubid army for more than a week. The fighting ended on 6 October, with the Ayyubid army withdrawing to Mt. Tabor.

However, 4 years later the Crusaders retreated from the area after the defeat in the battle of the Horns of Hattin.

- Mameluke period

* Battle of ‘Ain Jalut:

The Battle of ‘Ain Jalut (also spelled Ayn Jalut or Ein Harod) was a significant historical battle that took place on September 3, 1260, near the Harod spring in the Jezreel Valley. It was fought between the Mameluke Sultanate of Egypt and the Mongol Empire. The battle is notable for being one of the few instances where the Mongol advance was halted and for preventing the Mongols from extending their conquest into the Mameluke-ruled territories of the Middle East.

Battle of ‘Ain Jalut – AI generated by Bing

Key points about the battle include:

- Mongol Expansion: The Mongol Empire, led by Hulagu Khan, was in the process of expanding its territory westward after having already conquered large parts of Asia and the Middle East. The Mongols had recently captured and sacked Baghdad in 1258, leading to the collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate.

- Mameluke Sultanate: The Mamelukes were a group of warrior slaves who had risen to power in Egypt. Under the leadership of Sultan Qutuz, they had united to resist the Mongol advance into the region.

- Strategic Importance: The battle took place near ‘Ain Jalut, a crucial water source in the Jezreel Valley. Controlling this source was essential for any military operations in the area.

- Leadership: The Mameluke forces were led by Qutuz, who was also the ruler of Egypt at the time. The Mongols were commanded by Kitbuqa, a general in the Mongol army.

- Mameluke Victory: Despite being significantly outnumbered, the Mamelukes employed tactics that took advantage of the terrain and utilized their expertise in mounted warfare. They managed to defeat the Mongol forces and kill Kitbuqa.

- Impact: The Battle of Ain Jalut marked a turning point in the Mongol expansion. The defeat shattered the myth of Mongol invincibility, showing that they could be defeated on the battlefield. This event prevented the Mongols from further advancing into Egypt and the surrounding territories, securing the Mamelukes’ control over the region.

- Legacy: The battle is often seen as a symbol of the resilience of the Muslim world against foreign invasions. It also played a role in shaping the geopolitics of the region, as the defeat of the Mongols helped maintain the integrity of the Islamic territories in the Middle East.

The Battle of Ain Jalut has been remembered as a significant event in history, demonstrating that military strategy and leadership could overcome even seemingly unstoppable forces.

- Ottoman Period

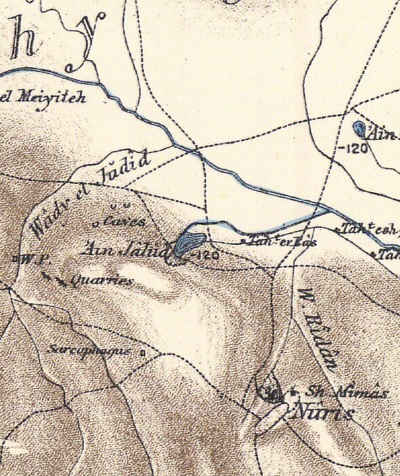

* PEF Survey:

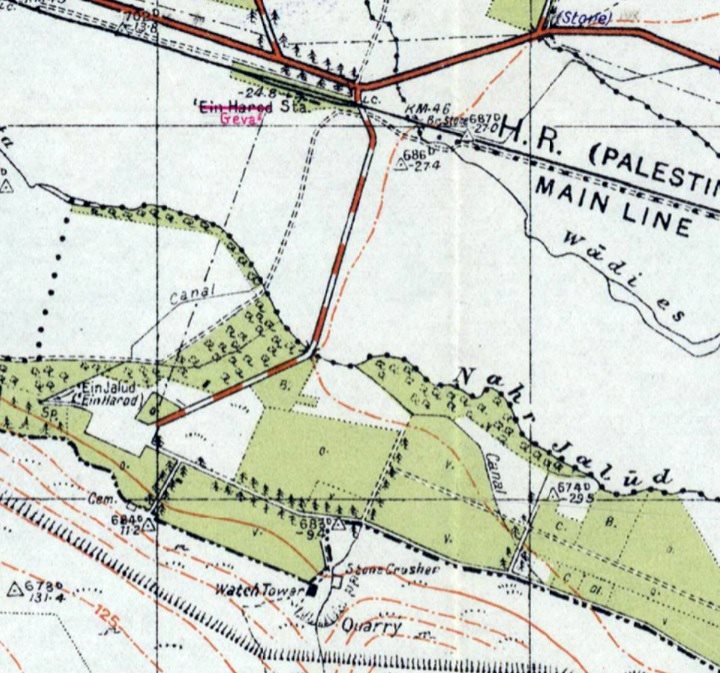

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP), commissioned by the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) in 1873. A section of their map is seen here, with the site marked as ‘Ain Jalud.

P/O Sheet 9 of SWP, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

A view of the spring is seen here, captured at the end of the Ottoman period (between 1898 and 1914). At that time the spring filled up a natural pool.

Gideon’s Fountain (‘Ain Jalud) – 1898 – 1914 – American Colony, Matson collection – Photos LOC

Mt. Gilboa is seen here totally barren, as David cursed the mountain after the death of King Saul and Jonathan in the battle with the Philistines (2 Samuel 1:21): “Ye mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew, neither let there be rain, upon you, nor fields of offerings…”.

- British mandate

A section of the British map of the 1940s is shown here.

https://palopenmaps.org – Palestine 1940s 1:20,000 map

In 1920 Yehoshua Hankin purchased 35,000 dunams from the Arabs of the Jezreel valley, thus creating the groundwork for the Jewish settlement in the valley. New settlements were founded in the valley – Kibbutz Ein Harod (1921), Kibbutz Tel Yosef (1921), Kibbutz Geva (1921), Moshav Kfar Yechezkel (1921), Beit Alpha (1922) and Hefzibah (1922). The new settlers had to drain the musqito-infected swamps and to build and support their farming settlements.

In 1931-1936 Hankin and his wife Olga built their house above the spring, but never lived there. They are buried in a tomb west of the house.

- Modern period

The spring is part of the Ma’ayan Harod national park. The park surrounds the spring and is a major regional visitor attraction.

Photos:

The photo shows the view of the northern foothills of the Gilboa mountain range. The road branches off highway #71, then turns west along the north side of the community settlement of Gidona.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

b. The Park

Ma’ayan Harod National Park offers a variety of facilities and attractions to provide a comprehensive and enjoyable experience for visitors:

- Lawns: The park features well-maintained lawns, creating a pleasant environment for relaxation, picnics, and social activities.

- Playground: A playground provides entertainment for families and children, allowing them to have fun and expend their energy in a safe and enjoyable setting.

- Swimming Pool: The presence of a swimming pool adds an opportunity for recreational swimming, especially during warmer months.

- Streams: The park’s natural streams contribute to its ambiance, offering a serene and soothing atmosphere for visitors to enjoy.

- Sports and Play Equipment: Sports and play equipment cater to various preferences, allowing visitors to engage in physical activities and games.

- Dressing Rooms and Toilets: Adequate dressing rooms and restroom facilities ensure visitors’ comfort and convenience.

- Youth Hostel: The availability of a youth hostel provides accommodations for those who wish to stay overnight and fully immerse themselves in the park’s offerings.

- Amphitheater: The large amphitheater with seating for 6,000 attendees provides a venue for performances, cultural events, and entertainment, making the park a hub of community and cultural engagement. It is 500m west of the park.

The diverse array of amenities and attractions within Ma’ayan Harod National Park showcases its dedication to providing a wide range of experiences for visitors of all ages. Whether visitors are seeking relaxation, outdoor activities, or cultural events, the park aims to cater to these various interests, making it a versatile and appealing destination.

Below is the posted map of the park.

Posted map of the park – courtesy of Mayan Harod National Park

Harod spring emerges from “Gideon’s cave” at the bottom of the mountain. The waters flow along a clear brook into a large paddling pool and into other streams flowing throughout the national park.

The flow of the spring originates from fault lines that traverse the Gilboa mountain range along a northwest-southeast axis. Fault lines are fractures in the Earth’s crust where blocks of rock have moved past each other. In this case, the movement along the fault lines has created a pathway for groundwater to emerge as a spring, contributing to the water source that feeds the park’s streams, pools, and other water features. The geological activity along these fault lines has shaped the hydrological characteristics of the area and adds to the unique natural setting of the park.

The emergence of water at a rate of 360 cubic meters per hour from the spring at Ma’ayan Harod National Park is quite substantial and contributes significantly to the park’s water features. Additionally, the relatively low salinity level of 283 mg of chlorine per liter classifies the water as “sweet,” which means it has a low concentration of dissolved salts. This sweet, fresh water is ideal for sustaining the park’s aquatic life, vegetation, and providing a refreshing water source for visitors.

The unique combination of a substantial flow rate and low salinity makes this spring a valuable natural resource within the park’s ecosystem, enriching the landscape and supporting the diverse flora and fauna that thrive in and around the water features.

Hankin’s Tomb is positioned above the spring. It is adjacent to Hankin’s old house, which has now been transformed into a museum. A staircase leads up to the house and the tomb, starting from the eastern side of the spring. This staircase provides access for visitors to reach the tomb area.

Conversely, a pathway descends from the western side of the tomb. This pathway allows visitors to walk downhill along the western side, possibly providing an opportunity to take in the view of the park and its surroundings from a different perspective.

From Hankin’s Tomb, visitors can enjoy a sweeping panorama, capturing the natural beauty and features of the park, as well as the surrounding landscape. The scene includes the streams, pools, and lawns nestled amidst the nearby trees. The parking lot is situated in a brighter area just beyond.

Further out, the backdrop showcases the picturesque Harod Valley, adorned with agricultural fields and fish ponds. In the distance, Moshav Kfar Yehezkel emerges behind the ponds, adding a touch of human settlement to the serene scenery.

The farthest reaches of the view reveal the eastern part of Mount Moreh. According to the Biblical story, the Medianites were stationed in the valley seen here in the background, while Gideon was stationed near the spring (Judges 7,1): “Midianites were on the north side of them, by the hill of Moreh, in the valley.”

e. Monument

West of Hankin’s tomb, within the park, there is a memorial dedicated to the fallen soldiers of the Jezreel Valley. This memorial was designed by the sculptor David Palumbo. It serves as a tribute to those who sacrificed their lives in service of their country and commemorates their memory within the context of the park’s historical and cultural significance. The location within the park adds a layer of remembrance to the natural beauty and historical importance of the area.

Links and references:

* References:

- Ma’ayan Harod national park

- IAA survey – Map 62 site 14

- Ma’ayan Harod visit – Israel’s Good Name – blog July 2023

- Nuris, ‘En Harod quarry – HA-Esi 131 2019

- Gideon at Harod Spring – YouTube, 3:33 minutes, Hebrew

* Internal:

- Giv’at Yonathan – ancient walled city of Ein Harod?

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- BibleWalks YouTube channel

Etymology (behind the name):

- Gideon (גִּדְעוֹן): derived from the Hebrew verb “gāda” (גָּדַע), which means “to cut off” or “to hew down.” The name can be interpreted to mean “one who cuts down” or “mighty warrior.” This meaning is quite fitting considering Gideon’s role in the biblical narrative as a leader who led a smaller group of warriors to victory against a larger enemy force.

- Harod -“Harod” (חָרוֹד) is derived from the Hebrew root word “charad” (חָרַד), which means “to tremble” or “to be afraid.” The name “Harod” itself can be translated as “trembling” or “fear.” The connection between the name “Harod” and the spring in northern Israel, known as “Ein Harod,” likely relates to the geographical and historical context. The area around the spring has been associated with significant events in biblical history, such as the story of Gideon. The name might symbolize the awe or reverence inspired by the natural beauty of the spring and the historical events that took place there.

- Ein – Hebrew for spring (‘Ain in Arabic)

- Ein Jalut – The name “Ain Jalut” is derived from Arabic. “Ain” (عين) means “spring” or “water source,” and “Jalut” (جالوت) is the Arabic name for Goliath, the biblical figure known for his battle against the young David. The name “Ain Jalut” can be translated as “Spring of Goliath” or “Goliath’s Spring.”

- “Ein Harod (Meuhad)” and “Ein Harod (Ihud),” are two kibbutzim located in northern Israel. They are situated near the Harod spring and named after it.

- Ein Harod (Meuhad): This kibbutz was established in 1921 and is part of the Kibbutz Movement. It played a significant role in the early Zionist settlement in the region and has historical importance due to its involvement in various aspects of Israeli society and culture.

- Ein Harod (Ihud): Established in 1921 as well, this kibbutz is a different community from Ein Harod (Meuhad). It is part of the Hashomer Hatzair movement. Like its counterpart, it has a history of contributing to the development of the region and the Israeli society.

BibleWalks.com – Discovering the Biblical scenes

Ein Haddah <<<—previous Yizreel Valley site—<<< All Sites>>>—next site —>>> Tel Amal

This page was last updated on Nov 30, 2024 (add AI images of Gideon, links)

Sponsored links: