Ruins of a huge fortress dated to the Crusaders and Mameluke periods, on a high hill above the city of Zefat.

* Site of the Month July 2016 *

Home > Sites > Upper Galilee > East > Zefat Fortress (Safed, Safad)

Contents:

Overview

Location

History

Photos

* Overview

* Mamluke Gate

* Crusaders walls

* Foothills

* Summit

* Park

Etymology

Links

Overview:

The huge fortress on the high hill above the city of Zefat was first fortified during the great revolt against the Romans. Massive fortifications were built during the Middle Ages by the Crusaders and Mamlukes. It dominated the Galilee and protected the route from Acre to Damascus. Matthew 5: 14: “A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid.”.

The fortress was destroyed by the great earthquake of 1837, then most of its stones were used to rebuild the ruined city around it. Zefat became one of Judaism’s four Holy cities, and a center of Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah).

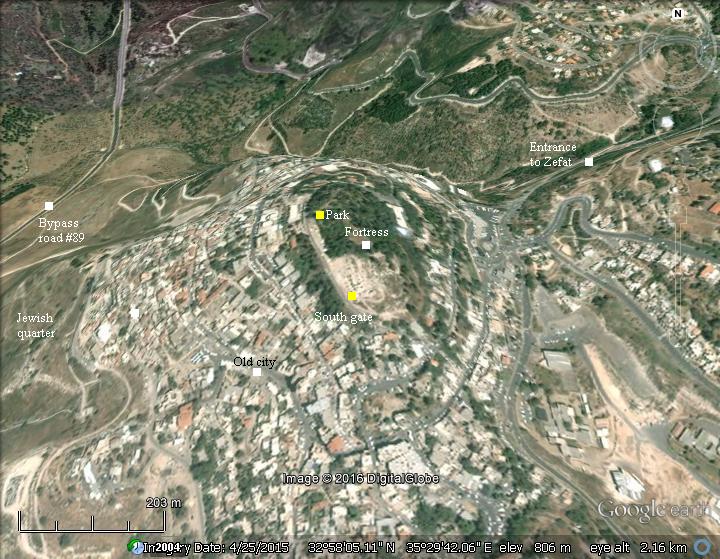

Location and map:

The summit is at an altitude of 846m, about 70m higher than the valley to the northeast of the hill, and 150m above the Jewish cemetery on its west side. This gave the fortress a strong natural defense.

Access to the park is from the eastern entrance to Zefat, via Jerusalem street, then turn left up Ha-Palmakh street on the way up to the old city, finally turning right to Hativat-Yiftah street.

History:

The PEF survey of 1866-1877 provided a brief history of the city (Volume I, sheet IV, pp. 249-250):

“Safed.This town seems probably to be the Tziphoth of the Egyptian hieratic M.S. called ‘Travels of a Mohar’ (see ‘Records of the Past,’ vol. ii. p. 62), mentioned with Kedesh, Tamena (Tibnin), Cophar Marron (possibly Meiron), and other places in Upper Galilee. In the Talmud the town is called Tzephath, and mentioned as a place fit for a signal-station (Tal. Jer. Rosh hash-Shanah, ii. 2). The Seph of Josephus, in Upper Galilee (B. J. ii. 20, 6), is also generally identified with Safed. Possibly also the Saphoth mentioned (Ant. xiii. 12, 5) as near Jordan, where Alexander Jannaeus met and defeated Plolemy Lathyrus, was the same place as Seph.

Sephet is also mentioned in the Vulgate text of Tobit i. I (‘that city’ in the Greek) ; and allusions to this passage are observable in later writings. In the twelfth century the tomb of Tobias is mentioned in a cave near Sephet (‘Citez de Jherusalem’), and in 1322 A.D. Marino Sanuto speaks of Sephet as a very strong place between Ptolemais and the Sea of Galilee, and places the Nephtalim of Tobit at or near it (Lib. III. Part VI. cap. 18). Since the sixteenth century many writers have identified Safed with Bethulia (see Khan Jubb Yusef, above ; cf. Robinson’s Bib. Res., vol. ii. p. 425, second edition). Fetellus, however, places Bethulia only four miles from Tiberias, and Marino Sanuto places Mount Bethulia above and apparently west of Dothan, which he places on his map west of Tiberias. In the thirteenth century, Saphet is noticed among the fiefs of the Teutonic Knights (Tables of the Teutonic Order).

R. Samuel bar Simson, in 1210 A.D., mentions Safed as inhabited by numerous Jewish communities; R. Jacob of Paris (1258 A.D.) places the tomb of R. Dosa bar Harcenas (mentioned in Pirke Aboth, iii. 10) at Tzephath. In 1334 A.D. R. Isaac Chelo found Jews from all parts of the world at this town. He notices an ancient synagogue and a public school. The tomb of R. Dosa and his son Hananiah is mentioned also by R. Isaac, in a cavern with a carob-tree before the entrance. In the sixteenth century many other Rabbis are noticed as buried near the town, which was a place of pilgrimage (Yikhus ha Tzadikim and.Yikhus ha Aboth), and many famous Rabbis were living at this time in Safed. (See Robinson’s Bib. Res., vol. ii.,’p. 429.)

The castle of Safed was standing as early as 1157 A.D. (William of Tyre, xviii. 14; cf. xxi. 28 and xxii. 16). It was built as a defence for the Christian kingdom against the Sultan of Damascus by King Fulke of Anjou (1131 to 1144 A.D. See Jaques de Vitry, chap, xlix., and Marino Sanuto). It capitulated to Saladin in November, 1187, after five weeks’ siege (‘ Vita Saladini ‘). It was dismantled in 1220 A.D., but rebuilt and enlarged in 1240-1260 A.D. Bibars took it in 1266 A.D., and strengthened and enlarged it. (See Robinson’s Bib. Res., vol. ii. p. 427, second edition.) The castle was rebuilt in the middle of the eighteenth century by ‘Aly, son of Dhaher el ‘Amr, and was the capital of one of the eight districts ruled by the Zeidaniyin. The great earthquake of the 30th of October, 1837, reduced the castle to a heap of ruins, and it has not been since rebuilt”.

-

Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

The city and the fortress were examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. This is part of their report on the city (Vol 1, Sheet IV, pp199-200):

“Safed – This is the capital of the district, and is situated on the top of high hills surrounded by steep valleys. The houses are well built of stone, and surround the castle . The population is about 3,000 Moslems, 1,500 Jews, and fifty Christians. The Moslems are about half of them Algerines, followers of ‘Abd el Kader in his exile. The Caimacam of the district resides here, and there is a Kadhi with some troops under an officer to maintain order in the district.

The city is divided into several quarters, situated on the higher slopes and on the plateau of the hill, and separated from each other by valleys and gardens planted with vines, olives, and figs. In the north quarter reside the Jews, numbering about 7,000; to the south and the east, the Mussulmans, about 6,000 in number. As to the Christians, they do not exceed 150 in number, and their quarter is between the two preceding. They are United Greeks, who only obtained permission to build a chapel and have a priest in 1864. The Jews, who have come here from different countries, have several synagogues. The part of the city which they occupy was almost entirely destroyed by the earthquake of 1837, the greater number of the houses having been entirely overthrown by the violence of the shocks. Nearly 6,000 people, of whom 4,000 were Jews, remained buried under the debris of their dwellings. The Jews felt the shock more severely than their neighbors because their houses were less solidly constructed, and because many of them were built almost on the roofs of those lower on the slopes. Their quarter is badly kept, and the streets or lanes which intersect it are covered after rain by a thick and pestilential mud, which causes frequent epidemics… – Guerin”.

Part of map sheet 4 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener,

1872-1877. (Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

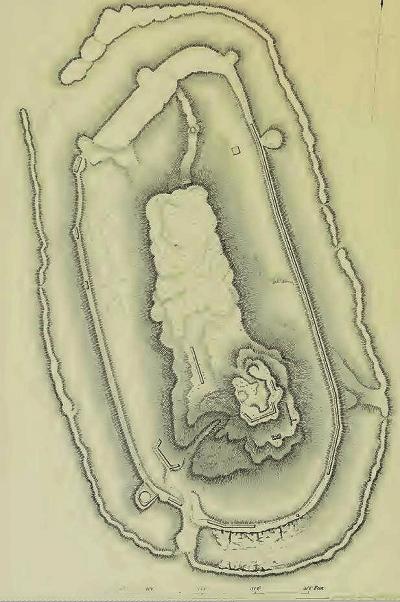

The report also describes the castle and provides a rough diagram (pp 248-250):

“El Kulah, or Kulat Safed – This was originally a Crusading castle, but of that there remains but little. Vaults and entrances to cisterns still show Crusading work, but the principal remains are those of the castle that Dhaher el ‘Amr built here at the time that he defied the Turkish Government, and governed this part of the country by force. Excavation might show Crusading remains hidden beneath the modern ruins. A vault that runs in a circular direction round the top of the castle shows good Crusading masonry. Some of the stones are 6′ 5″ long by 2’ 5″ wide. They are well fitted together with cement, and the round arch is built on a curve, as shown by the plan. The stones have a slight draft, varying from 1 1/2″ to 2″ wide. They are hammer-dressed nearly on a level with the draft.”.

“Underneath this there are large vaults, at present inaccessible. This was probably the citadel of the castle. To the southeast

there is the entrance to large cisterns. This is also built of large stones ; it is probably of Crusading work. The rest of the remains of the castle are of small rubble masonry faced with well-dressed stones of small size, and are the work of Dhaher el ‘Amr.

The castle of Safed is rarely mentioned in Crusading history. It was probably built by King Fulke about 1140 (Marin. Sanutus, p. 166). It is mentioned by William of Tyre as the place to which King Baldwin III. fled after his defeat in 1157 A.D. (book xviii. chap. xiv.). It is also mentioned book xxi. chap. xxviii., and book xxii. chap. xvi. Jacob de Vitry also mentions Safed (chap. xlix. p. 1074). The defence of the castle appears to have been entrusted to the Knights Templars, who claimed all the country west of it (book xxi., chap. xxx.).

After the battle of Hattin, in October of 1188, Saladin took Safed. It is then described as a strong castle. In 1220 el Melek el Mu’adhdhem caused Safed to be destroyed, for fear of the Christians getting possession of it . In 1240 it was given up to the Christians after the treaty with the Sultan Ism’ail of Damascus, when Kul’at esh Shukif and Tiberias were also surrendered. The Templars rebuilt the castle owing to the efforts of Benedict Bishop of Marseilles. He laid the foundation-stone, and saw it completed in 1260. In 1266 it was taken by el Melek ed Dhaher Bibars, after he had failed to obtain possession of Montfort. It was strengthened by Bibars. The castle was much destroyed by an earthquake in 1759″.

PEF Survey, Volume 1, Sheet IV, p. 248

‘The summit of the hill at Safed is crowned by the ruins of a great elliptical enclosure the entrance of which is towards the south. It is surrounded by a fosse partly cut in the living rock, and three parts filled up. It was formerly flanked by ten towers, which have lost their casing of cut stones, and now possess nothing but the inner rubble. A second fosse runs within, and beyond it is the castle properly so called, now nothing but a confused mass of rubbish : it was flanked by lowers at the angles, and was provided with great and deep cisterns. Every day some of it is taken away, as it serves for a quarry for the inhabitants of the city. A powerful tower or keep, of circular form, measuring thirty-four metres in diameter, dominated the castle, which in its time dominated the city ; there remain several courses composed of regular blocks worked with much care. Within one remarks the debris of a vaulted gallery constructed with similar blocks.’ Guerin”.

- Modern Period

In the years 2001-2003 the IAA, with the funding of the Israeli tourism Corporation, conducted a conservation of the southwestern area of the fortress. The exposed ruins cover a fraction of what was once the Crusaders largest castle in the Levant. It is now an open park, highly recommended for a visit in this unique Holy city.

Photos

(a) Overview:

An aerial view from a drone shows the south west side of the hill. On this side are the main visible fortifications, including the south gate. The lower section of the gate and the upper section on the summit are Mamluke ruins, while the middle range are walls from the Crusaders period.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The next aerial shot is from the same spot, but with a view towards the north, showing the extent of the hill. The fortress once covered the entire area of the hill, but was dismantled after the 1837 earthquake.

According to a 13th Century report, the fortified area of the Crusader fortress extended to 112m by 252m, a total of 40 Dunam (4 Hectares). Other reports measured the fortified area at 300 by 170m. It was protected by a double curtain wall – a common medieval fortification design of defensive walls around towers. The total circumference of the walls, according to the Medieval report, was 580m (inner wall) and 825m (outer wall).

The hill was replanted and opened as a public park, with the excavated area located on its southwest side.

![]() An aerial view of the west side can be seen in the following YouTube video:

An aerial view of the west side can be seen in the following YouTube video:

(b) South Gate:

The area of the south gate was exposed and reconstructed by the archaeologists. It is seen in this aerial view from the south west side. The fortifications are dated to the Mamluke period (the lower side of the gate) and the Crusaders period (on a higher level).

The following photo shows a view of the bottom of the gate. These walls are dated to the Mameluke period, initially built in the years 1266-1267 after the Mameluke conquest of the fortress.

A closer view of the entrance to the gate is seen in the photo below. Notice the two arrow loop niches on the wall behind Orna (designated as wall #W100 on the IAA report).

Behind this wall was the gateway into the gate. A massive tower, seen in the following photo on the right side, was located above the gateway. The entrance to the tower was through a stepped ramp (S4 on the IAA report), 24m long and 7m-8m wide .

Another view of the ramp, from the inner side of the tower, is in the following photo. Water drainage was located on both sides along the walls. At a later construction phase, a new wall (W132) was added on the north side in order to narrow the approach. An additional low wall (W152, where Orna is sitting) was added in order to better protect the entrance. These changes may have been made after an earthquake shook the fortress.

During the cleaning of the debris of the ramp, the archaeologists uncovered a section of a large limestone lintel bearing a figure of a prancing lion or cheetah. This was the symbol of Mameluke ruler Bybars, as found in other Mameluke fortresses (Nimrod) and bridges (Lydda). It decorated the ramp entrance.

- Gate Tower

The massive gate tower, 15m by 20m, was located above the gateway. It was exposed to most of its height.

Two broad windows are located on the walls of the tower, which provided light into the tower’s inner room. They probably contained arrow loops, but these were not found in the rubble.

The walls of the tower are 7m thick, as seen in the opening of the left wall (W107) below.

Sections of the large square wall (W107) on the west side of the tower, seen on the right side of the photo above, was still standing during the PEF survey. It is marked on the 19th Century PEF plan by a yellow square on the illustration.

The gateway turns to the left on the eastern side of the tower, and ascends to the main defensive enclosure (“enceinte”) of the fortress.

(c) Crusaders walls:

Above the gate area, which was constructed during the Mamluke period, are earlier sections of the Crusaders walls.

They are seen just above the tower room.

These walls were constructed by the Franks Crusaders starting in 1101, then handed over to the Templars order in 1168. The quad rectangular room (S12), seen where the steps turn to the right to W200, was roofed by a vault. In the room on its east side (S15) a carved head was discovered. On the south of room S15 was a plastered cistern (S14), seen here on the bottom left side.

To the north of the gate area is a section (wall #200) of the Crusaders wall, one of the two curtain walls that surrounded the fortress. The first unit is 25m long, 2m wide, and is seen on the top of the following photo. This section of the wall has five arrow loop niches, with narrow (9 cm) slits.

An arch connects to wall W200. It connected both sections (W200, W109) of the inner wall, and created a space S8 between the arch and the side of the tower. This arch may have been the ruins of a Crusader period gate, and after the Mamluke modifications it was left inside the walls.

Another unit of the Crusader curtain wall is located farther south, near the tower gate. This wall (W109, marked in yellow), which 6m of it was exposed by the archaeologists, is thicker (3.2m).

An inner wall (W210) runs in parallel to the inner face of the external wall, and is marked with red square.

These twin walls curved around the south end of the hill, meeting another section of the curtain wall (W300) on the south-east side.

(d) Foothills:

An aerial view of the area above the south gate is in this photo.

The trail leads up to the summit.

Sections of the base of the big, circular tower (wall #400) is seen in the following photo. It is dated to the Mamluk period.

Remains of a vault that runs in circular direction are observed on the edge of the circular tower:

-

Circular Tower gate and ascending passage

A gate and entrance into the circular tower is located on its west side. The roof, supported by arches, is now gone.

From the gate area, a ring-shaped inner corridor starts ascending upwards towards the south. In the Medieval times, the corridor was covered by a roof, ascending into the guts of the circular tower.

Walking along the corridor, it is blocked at some distance away. Notice the bases of the supporting arches along the right side.

(d) Summit:

On the summit of the circular tower is a modern monument commemorating the fallen soldiers of the Independence war. A self operated audio recording also supplies information on the history of the place, in both Hebrew and English versions.

The top of a large circular cistern is located near the monument. The cistern, 10m in diameter and 10.5m deep, was constructed by the Mamlukes.

The sign near the monument describes the operation to conquer the city. On May 6, 1948, the Palmach (“Strike forces”) attempted to capture the hill during the night. Due to it height and strong defenses, the attempt failed with casualties. The second attempt on May 9 was successful, and the capture of the hill brought the whole city under Jewish control on the next day, breaking the siege off the Jewish quarter. The independent state of Israel was declared just four days later on May 14.

From the observation point on the summit are great views of the city and its surroundings.

On the south side of the summit are ruins of a large Ottoman-period structure that once stood above the circular tower, but now gone after it was dismantled in the 19th Century.

A panoramic view from this spot is shown in the next photo. Pressing on this picture will pop up the panoramic viewer. Using this flash-based panoramic viewer, you can move around, zooming in and out – viewing the site in the amazing full screen mode (like you are really there). Major sites are marked on the views. It may take minutes to upload, but then its worth the waiting time.

To open the viewer, simply click on the photo, then tour the area around:

(e) Park:

After the severe earthquake of 1837 that devastated Zefat, the fortress was in ruins. Most of its stones were then stolen and reused to rebuild the houses around the hill. Therefore, there are few other remains of this large fortress that are visible on the hill.

A park was planted on the hill and along its foothills.

This nice park, together with the reconstructed fortifications on the south side of the hill, are a great place to start a visit in Zefat.

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the city:

-

Zefat, Tsfat – the Hebrew name of the city, based on the root word “Tsafa” (overlook or lookout), as the city is located on a high hill overlooking the Galilee.

-

Seph – the name as appears in Josephus Flavius history book where he wrote about his own acts to fortify the Galilee including Seph, meaning Zefat (Wars 2:20:6): “Moreover, he built walls about the caves near the lake of Gennesar, which places lay in the Lower Galilee; the same he did to the places of Upper Galilee, as well as to the rock called the Rock of the Achabari, and to Seph, and Jamnith, and Meroth”.

-

Safed – the name as appears in the PEF report

-

Safad, Saphet – other forms

Links:

* External sites –

- Zefat – the western slope – Yosef Stepansky [Hadashot Arkheologiyot 119, 2007]

- Zefat – Hervé Barbé and Emanuel Damati [Hadashot Arkheologiyot 117, 2005]

- Zefat – eastern slope – Edna Delali-Amos [Hadashot Arkheologiyot 125, 2013]

* Nearby sites:

- Tel Yaaf and Rosh Pinna

- Rock of Akhbara

- Naburiya – ruins of a Roman/Byzantine Jewish village and synagogue

* Other links:

- Aerial views of the Holy Land sites

- Youtube – more Aerial videos

BibleWalks.com – Walking the Bible trails

Abel Beth Maacah <<<–previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Upper Galilee site—>>> Ateret Fortress

This page was last updated on Jan 15, 2016

Sponsored links: