Shomron (Samaria) was the capital city of the Northern Kingdom, established by Omri and Ahab. An important Hellenistic and Roman cities in the Holy Land.

* Site of the month Feb 2013 *

Home > Sites > Samaria > Samaria City (Shomron, Sebaste)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Structure

Photos

* West Gate

* Colonnaded Street

* Forum

* Hippodrome

* Theater

* Israelite Wall

* Hellenistic Wall

* Augusteum

* Ahab’s Palace

* St. John

* Crusaders Church

* Area Views

* Panoramas

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Samaria, also known as Shomron in Hebrew, is a city located in the northern region of Israel. It is situated between the cities of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and is the capital of the Samaria District.

The city has a rich history that dates back to Biblical times. It was once the capital of the Kingdom of Israel during the reign of King Omri and his son, King Ahab. 1 Kings 16 23-24: “Omri … bought the hill Samaria of Shemer for two talents of silver, and built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, after the name of Shemer, owner of the hill, Samaria”.

The city was later destroyed by the Assyrians in 722 BC, and the inhabitants were exiled to other parts of the Assyrian empire.

During the Roman and Byzantine periods, Samaria was rebuilt and became an important center of trade and commerce. It became one of the most important Roman cities in the Holy Land. A temple dedicated to Augustus was constructed by Herod the Great, as well as other grand public structures. It was also a center of Christian pilgrimage, as it was believed to be the site where Jesus spoke with the Samaritan woman at the well.

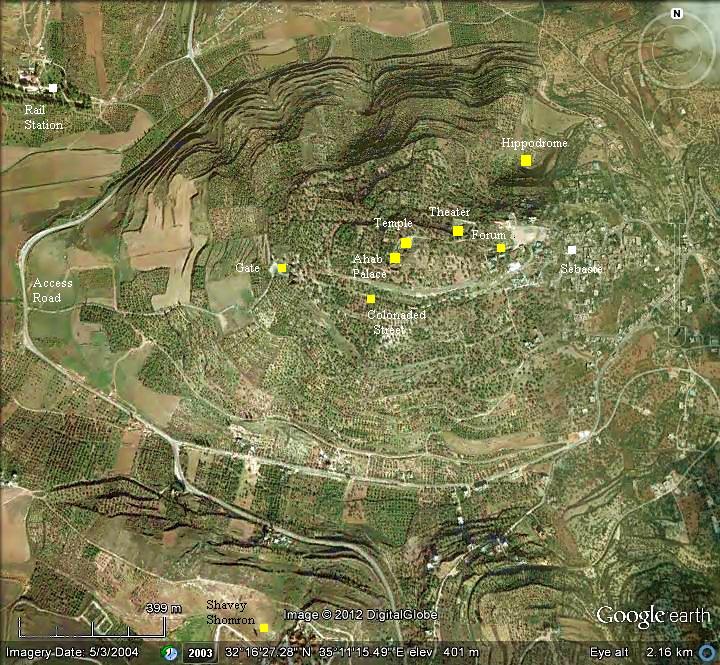

Location and Map:

The ruins of the city of Samaria/Shomron are located on the top of a high hill, on the west side of the ancient route from Shechem to the north. On the eastern slopes of the hill is the Arab village of Sebaste, and 1km to the south is the new settlement of Shavey Shomron.

History:

-

Established by King Omri (9th century BC)

Omri was a general in the army of Israel. He became a king over the Northern Kingdom (882BC) during the mutiny of Zimri (1 kings 16 16): “And the people that were encamped heard say, Zimri hath conspired, and hath also slain the king: wherefore all Israel made Omri, the captain of the host, king over Israel that day in the camp.”. Omri killed Zimri, engaged in a civil war, and won it (1 Kings 20 21-22):

“Then were the people of Israel divided into two parts: half of the people followed Tibni the son of Ginath, to make him king; and half followed Omri. But the people that followed Omri prevailed against the people that followed Tibni the son of Ginath: so Tibni died, and Omri reigned.”.

After regaining the control of his Kingdom, Omri turned to defend his country against their arch-enemy – Aram-Damascus.

The city became the capital of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, replacing the former center in Tirzah. It was established at about 876 BC (Iron Age II) by King Omri, who purchased the hill from its owner, Shemer. The city was named Shomron, based on the name of the owner, as described in the Bible (1 Kings 16 23-24): “In the thirty and first year of Asa king of Judah began Omri to reign over Israel, twelve years: six years reigned he in Tirzah. And he bought the hill Samaria of Shemer for two talents of silver, and built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, after the name of Shemer, owner of the hill, Samaria”.

This change of the central administration came from a number of reasons:

(a) A strategic location near two major roads:

- north from Shechem thru En-Ganim (Jenin) and then to the Galilee;

- west towards the plains and the Way of the Sea.

(b) A better centralized location: the Kingdom of the North extended to the Upper Galilee and to the sea, while Tirzah was located on the south-east corner.

(c) The need for better protection, to handle the threat of the arch enemy of Aram (Syria) from Damascus.

(d) Follow the acts of David, who upgraded the capital from Shiloh to Jerusalem

Shomron’s location is shown in the center of the Biblical map below (red circle). Tirzah, the former center of the Kingdom of the north, is located 14KM to the east.

Map of the area around Samaria/Shomron (red dot) –

during Canaanite Thru Roman periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

Omri reigned for 12 years (882-869 BC), and was replaced by his son Ahab (1 Kings 16 28-29): “So Omri slept with his fathers, and was buried in Samaria: and Ahab his son reigned in his stead. And in the thirty and eighth year of Asa king of Judah began Ahab the son of Omri to reign over Israel: and Ahab the son of Omri reigned over Israel in Samaria twenty and two years”.

-

Ahab – Siege of Shomron (9th century BC)

Ahab, son of Omri, continued his father’s defensive acts against the danger from the north, and also made the Kingdom stronger and prosperous. Evidence of his fortifications and the wealth of his Kingdom can be found in the excavations of the main cities of the Northern Kingdom: Hazor, Jezreel, Megiddo and Rechov (Stratum IV).

Aram-Damascus (Syria) fought 3 wars against the Northern Kingdom. The first intrusion occurred in 855 BC, when they placed a siege on the city. (1 Kings 20 1):

“And Benhadad the king of Syria gathered all his host together: and there were thirty and two kings with him, and horses, and chariots; and he went up and besieged Samaria, and warred against it”. Ahab defeated the Syrians and saved the city (1 Kings 20 20-21): “And they slew every one his man: and the Syrians fled; and Israel pursued them: and Benhadad the king of Syria escaped on an horse with the horsemen. “.

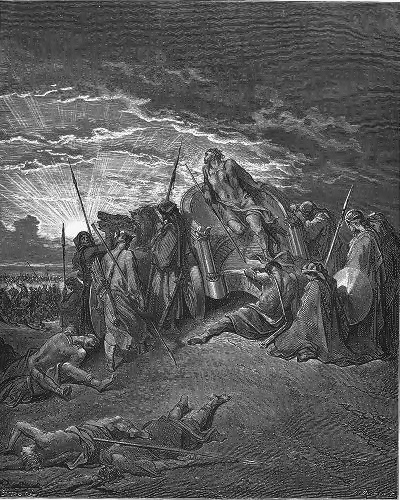

Ahab continued to fight Aram-Damascus in two more battles, but was killed (850) in the last one in Ramoth-Gilead, and was buried in Samaria (1 Kings 22 35-38):

“And the battle increased that day: and the king was stayed up in his chariot against the Syrians, and died at even: and the blood ran out of the wound into the midst of the chariot. And there went a proclamation throughout the host about the going down of the sun, saying, Every man to his city, and every man to his own country. So the king died, and was brought to Samaria; and they buried the king in Samaria. And one washed the chariot in the pool of Samaria; and the dogs licked up his blood; and they washed his armor; according unto the word of the LORD which he spake”.

Ahab’s son Yoram continued to confront the Syrians, and was killed in Jezreel (842), thus ending the house of Omri.

Fall of King Ahab in Ramoth Gilead

Drawing by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

Aram-Damascus continued their assaults: An intrusion, headed by Hazael in 815-810, captured and enslaved the Northern Kingdom, as per Biblical accounts (2 Kings 8:12, 12:18-19, 13:3+7; Amos 1:3) and (2 Kings 10 32): “In those days the LORD began to cut Israel short: and Hazael smote them in all the coasts of Israel;”.

This grip on Israel was released by the Assyrians, who captured Damascus (806 BC), thus weakening Aram-Damascus, but left Israel alone. Therefore, for the following 74 years, the Northern and Southern Kingdoms of Israel managed to expand their territories and prosper.

However, this expansion also brought friction between the two Kingdoms. In the fields near Beth Shemesh the two Israelite kingdoms clashed at 786BC. The Northern Kingdom (based in Samaria) defeated the Kingdom of Judah, and Jerusalem was sacked (2 Kings 14:11-14):

“But Amaziah would not hear. Therefore Jehoash king of Israel went up; and he and Amaziah king of Judah looked one another in the face at Bethshemesh, which belongeth to Judah. And Judah was put to the worse before Israel; and they fled every man to their tents. And Jehoash king of Israel took Amaziah king of Judah, the son of Jehoash the son of Ahaziah, at Bethshemesh, and came to Jerusalem, and brake down the wall of Jerusalem from the gate of Ephraim unto the corner gate, four hundred cubits. And he took all the gold and silver, and all the vessels that were found in the house of the LORD, and in the treasures of the king’s house, and hostages, and returned to Samaria.”.

The Northern Kingdom captured the area of Aram-Damascus, thus expanding their area north of Damascus. These were the golden years of Shomron. However, the danger was not over, and prophets such as Amos tried to warn against the smugness of the kings (Amos 6 1): “Woe to them that are at ease in Zion, and trust in the mountain of Samaria, which are named chief of the nations, to whom the house of Israel came!”.

-

Assyrian Conquest (8th century BC)

The Assyrians, the new rising empire, was another threat from the north.

Shalmaneser III was the Assyrian king who invaded to Israel in the first Assyrian intrusion (841 BC). His forces reached the Galilee and Horan, destroying several cities such as Hazor. However, the Assyrians had to focus on wars in other regions of their empire, and left the area.

In 734 the Assyrians first conquered the coast of Israel, reaching Gaza and the border of Egypt. This time they bypassed the Northern Kingdom.

In 732 BC was an intrusion to the North of Israel by the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III, who annexed the area (as per 2 Kings 15: 29): “In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took … Galilee…and carried them captive to Assyria”. During this period the area of Shomron was spared, but the kingdom was reduced to a small size, and had to pay high taxes to the Assyrians.

Orthostat relief – depicting soldiers from different orders of the Assyrian Army, in procession;

basalt; Hadatu Tiglath-Pileser III period (744-727BC)

[Istanbul Archaeological museum]

The Egyptians, enemies of the Assyrians, encouraged the people in the occupied territories of the Assyrians to revolt following the death of Tiglath-Pileser. Hoshea, King of Northern Israel, joined this mutiny, but made a fatal mistake. This time the Assyrians crushed the remaining territories of the Northern Kingdom. The intrusions of Shalmaneser V and Sargon II in 724-712 crushed the Northern Kingdom and its capital city (2 Kings 17: 5-6): “Then the king of Assyria came up throughout all the land, and went up to Samaria, and besieged it three years. In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes”.

Thus ended the 157 years (876-720BC) of Shomron as the capital of the Northern Kingdom. The Assyrians occupied the city until the Babylonians conquered the land (about 604BC).

-

Samaritans (6th century BC)

According to inscriptions from Sargon’s palace at Khorsabad, the Assyrian king claims that 27,290 people in Samaria were relocated to Assyria, and the capital city Samaria (Shomron) was destroyed and later rebuilt by Sargon. As a common Assyrian conquest practice, the Israelite exiles were replaced by people from Mesopotamia and other areas (2 Kings 17 24-26):

“And the king of Assyria brought men from Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Ava, and from Hamath, and from Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel: and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof”.

These new people brought with them pagan beliefs. However, the new arrivals were a minority among the Israelites, and so they absorbed the Jewish religion.

The Bible writes that only after God punished them by sending lions – they converted their religion (2 Kings 17, 25-26):

“And so it was at the beginning of their dwelling there, that they feared not the LORD: therefore the LORD sent lions among them, which slew some of them. Wherefore they spake to the king of Assyria, saying, The nations which thou hast removed, and placed in the cities of Samaria, know not the manner of the God of the land: therefore he hath sent lions among them, and, behold, they slay them, because they know not the manner of the God of the land”.

God sends lions – by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

Thus, the Bible summarizes the origin of the Samaritans (2 Kings 17, 29): “Howbeit every nation made gods of their own, and put them in the houses of the high places which the Samaritans had made, every nation in their cities wherein they dwelt”. Therefore, the Samaritans came from other parts of the Assyrian empire, and converted to the local faith. They are often called “Cuthans” – named after one of the cities where they came from (40 km northwest of Babylon). Evidence of this origin may have been found in the excavations (Reisner & Fisher, 1908-1911) of the capital city Samaria/Shomron (Sebastia), where a 8th C South-Mesopotamian vessel was found by the archaeologists.

-

Persian and Hellenistic Periods (6th C – 2nd C BC)

The Babylonians replaced the Assyrian empire, but then was defeated by the Persians, who ruled the region from 538 to 332 BC. During this time the city was a administrative center.

In 332 BC Alexander the Great defeats the Persians, then marches south en route to Egypt. During the 7 months siege of Tyre, delegates from Israel came to meet Alexander. The Samaritan delegation, was headed by Sanballat, the Governor of Samaria. They sided with the Greeks and contributed 8,000 troops to Alexander’s Army.

After the siege of Gaza (332 BC, after 2 months of siege) and the Egyptian conquest (until spring of 331 BC), Alexander returned to the north. He, or one of his generals, attacked Samaria, since the Samaritans rebelled against the newly appointed Greek governor. The Greek army destroyed the city, and replaces its residents with thousands of veteran Macedonian soldiers. This started the Hellenistic period of the city.

The “Alexander the great” coins were very common during the Hellenistic period, and were then like the American dollar is today. The reverse side, seen below, shows Zeus – king of the gods – seated to the left and holding an eagle on his right hand, and holding a scepter with his left hand. The Greek letters to the right (“ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡoΥ”) spell: Alexander.

The Greek name of the city was Samaria, as written by Josephus (Ant. 8 Ch. 12 5): “in the city called Semareon, but named by the Greeks Samaria”.

Following the death of Alexander (321), Syria and Israel were incorporated into the Egyptian empire of Ptolemaic empire, which was founded by one of Alexander’s generals – Ptolemy “Soter”. This conquest ignited the 3rd war of the Diadochi (Alexander’s successors). His rival, Antigonus, fought and defeated the Ptolemy-Egyptian army in Tyre (314), destroyed the fortifications of Samaria (312), but then retreated (306). After the three sections of the Greek world finally stabilized their territories (285), Ptolemy was in control of Samaria once again.

The Seleucid empire was one of these Greek empires who tried to take control of Syria and Israel. The Seleucids, based in Antioch (located in southern modern Turkey), fought the Ptolemy-Egyptian army in several series of campaigns (276 thru 217 BC), but only in 198 the Seleucid king Antiochus III managed to capture Samaria and Jerusalem.

-

Hasmonean period (2nd – 1st century BC)

The Seleucid rulers changed their attitude to the Jewish population, and during the reign of Antiochus IV an uprising, lead by the Maccabeus, managed to free the Land and establish the Hasmonean Kingdom (164 BC).

The Hasmoneans expanded their territory, and captured and destroyed the Samaritan temple and administration center on Mt Gerizim. Samaria was besieged in 108-107 BC by the Hasmonean King John Hyrcanus I, then captured and demolished it (Josephus Flavius Antiquities 13, Chapter 10 2-3):

“So he made an expedition against Samaria which was a very strong city …but he made his attack against it, and besieged it with a great deal of pains; for he was greatly displeased with the Samaritans for the injuries they had done to the people of Merissa, a colony of the Jews, and confederate with them, and this in compliance to the kings of Syria. When he had therefore drawn a ditch, and built a double wall round the city, which was fourscore furlongs long, he set his sons Antigonus and Arisrobulna over the siege; which brought the Samaritans to that great distress by famine, that they were forced to eat what used not to be eaten, and to call for Antiochus Cyzicenus to help them…And when Hyrcanus had taken that city, which was not done till after a year’s siege, he was not contented with doing that only, but he demolished it entirely, and brought rivulets to it to drown it, for he dug such hollows as might let the water run under it; nay, he took away the very marks that there had ever been such a city there”.

Coin of John Hyrcanus

The fall of the city to the Hasmoneans, an important event in the Jewish history, expanded their empire to the area of the Galilee (103-104). Samaria was later resettled by the Hasmoneans during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus.

-

Early Roman Period – Sebaste (1st century BC)

The Roman legions under Pompey conquered Israel in 63BC, and cut the size of the Hasmonean territories. The city of Samaria became under Pompey’s new arrangements (63 thru 55 BC) an independent city, but part of Syria. Aulus Gabinius, the Roman general under Pompey, rebuilt the city in 58-57 BC.

Herod the Great, a Jewish Roman client King of Israel (39BC-4BC), was well connected with the Roman rulers. As a favorite of the court, Emperor Augustus (reigned 27BC – 14 AD) transferred to him several territories, which were previously lost during Pompey’s arrangements and Cleopatra’s changes, and added new cities. As a gratitude to Augustus, Herod rebuilds the city of Samaria and renames it to Sebaste (a feminine form of Sebastos, Greek for Augustus). He then constructs a temple of Augustus (“Augusteum”) in his protégé’s honor.

Josephus writes about the construction of the city and the temple in his book (Wars 1, 21 2):

“Yet did he not preserve their memory by particular buildings only, with their names given them, but his generosity went as far as entire cities; for when he had built a most beautiful wall round a country in Samaria, twenty furlongs long, and had brought six thousand inhabitants into it, and had allotted to it a most fruitful piece of land, and in the midst of this city, thus built, had erected a very large temple to Caesar, and had laid round about it a portion of sacred land of three furlongs and a half, he called the city Sebaste, from Sebastus, or Augustus, and settled the affairs of the city after a most regular manner.”.

In 37BC Herod marries his second wife, Miriammne, in the city of Samaria. She was the daughter of Alexander Maccabeus, thus Herod married into the royal Hasmonean family to strengthen his claim for the throne. Herod successfully captures Jerusalem, expands his kingdom, and reigns until 4BC. He is also known as the great builder – such as the temple of Jerusalem, establishment of Caesarea and other cities. Most of the antiquities found today on the hill are remains of the Herodian city.

Roman Roads:

In ancient times two major roads passed near the city of Sebaste/Samaria. These routes was used also during the Roman period. The routes passed on the west and south sides of the the city, connecting Shechem (Neapolis) to the north (Galilee, Nazareth) and to the west (Sharon, Caesarea).

These roads were identified and reported by Conder and Kitchener in 1882 (SWP, Vol 2, pp 160-161): “Samaria commands two main roads, that from Shechem, to the north which passes beneath it on the east, and that to the plain from Shechem, which runs west of it, in the valley, about two miles distant”.

The location of Samaria is marked by a red square on the Holy Land section of the Peutinger map, near the line of the road from Shechem to Caesarea.

The Peutinger Map (Tabula Peutingeriana) is a medieval map which was based on a 4th century Roman military road map. It is oriented west-east. Shechem appears as “Neapolis” in the center.

The location of the city of Samaria is indicated by a red square on the side of the road from Shechem to Caesarea. Another road, which is not indicated here, runs to the north (right direction).

-

Revolts against the Romans (1st century AD)

During the great revolt against the Roman (67-70AD), the city suffered damages from the Jewish fighters. Samaria was controlled by the Herodian Kings Agrippa I and II, who sided with the Romans.

A second revolt was ignited by Hadrian (132-135). This time, the city was out of the reach of the Jewish freedom fighters of Bar Kochva, and suffered no damages, while most of Israel was devastated. The Roman army camped in the city and staged attacks on Neapolis (Shechem).

-

Late Roman (2nd-4th century AD)

The Roman empire enjoyed peace and prosperity at the times of Septimius Severus (193-211 AD) . However, his reign started in a bloody conflict, which caused some of the cities and Roman legions stationed in Israel to fight among themselves. Samaria sided with Septimius Severus together with Legion VI, while Jerusalem and Legion X sided with the rival contender – Pescennius Niger of Syria. As a gratitude for their support during the civil war, he established the city as a colony in 201AD (“Colonia Lucia Septimia Sebaste”) and reconstructed the city, without major changes. Sebaste reached then its highest level of material prosperity.

Bust of Septimius Severus

(from Roman coin; 198AD)

-

Byzantine period (5th – 7th century AD)

During the 5th century AD a Byzantine church was built on the southern side of the acropolis, in honor of John the Baptist. According to the tradition, John’s body was buried in the city.

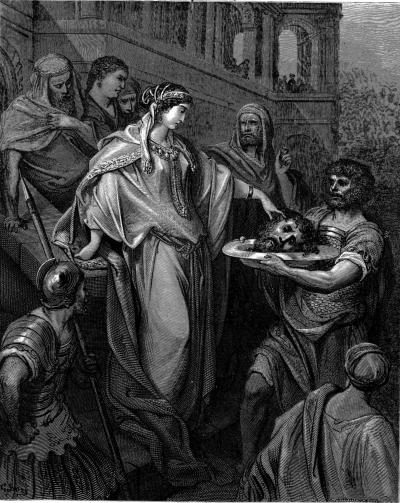

This New Testament text tells how King Herod Antipas (reign 20BC-39 AD), son of Herod the Great, killed John the Baptist (Mark 6, 17-29):

“For Herod himself had sent forth and laid hold upon John, and bound him in prison for Herodias’ sake, his brother Philip’s wife: for he had married her. For John had said unto Herod, It is not lawful for thee to have thy brother’s wife. Therefore Herodias had a quarrel against him, and would have killed him; but she could not:”.

” For Herod feared John, knowing that he was a just man and an holy, and observed him; and when he heard him, he did many things, and heard him gladly. And when a convenient day was come, that Herod on his birthday made a supper to his lords, high captains, and chief estates of Galilee; And when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee. And he sware unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom. And she went forth, and said unto her mother, What shall I ask? And she said, The head of John the Baptist. And she came in straightway with haste unto the king, and asked, saying, I will that thou give me by and by in a charger the head of John the Baptist. And the king was exceeding sorry; yet for his oath’s sake, and for their sakes which sat with him, he would not reject her. And immediately the king sent an executioner, and commanded his head to be brought: and he went and beheaded him in the prison, And brought his head in a charger, and gave it to the damsel: and the damsel gave it to her mother. And when his disciples heard of it, they came and took up his corpse, and laid it in a tomb”.

Herod’s daughter receives the head of John the Baptist-

Drawing by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

The Gospels wrote that his body was taken by his disciples and buried, but did not describe the location of the tomb. Centuries later, the tradition located his tomb in Sebaste, which is why the church was built here. A monastery was added to the church at a later date.

During the Byzantine period the city declined, and was totally destroyed during the Arab conquest (636 AD).

-

Crusaders period (12th century AD)

The Crusaders built a Latin church on the ruins of the eastern gate. It is also dedicated to John the Baptist, and built over the traditional site of his tomb which was accessed by a flight of steps. Remains of the church can be seen near the mosque of the Arab village, which was built over the church. Near these ruins are remains of Roman tombs.

-

Ottoman period (19th century)

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine in 1882. They reported on their account of the village of Sebaste (SWP, Vol 2, pp160-161):

“Sebustieh -A large and flourishing village, of stone and mud houses, on the hill of the ancient Samaria. The position is a very fine one ; the hill rises some 400 to 500 feet above the open valley on the north, and is isolated on all sides but the east, where a narrow saddle exists some 200 feet lower than the top of the hill. There is a flat plateau on the top, on the east end of which the village stands, the plateau extending westwards for over half a mile. A higher knoll rises from the plateau, west of the village, from which a fine view is obtained as far as the Mediterranean Sea. The whole hill consists of soft soil, and is terraced to the very top. On the north it is bare and white, with steep slopes, and a few olives ; a sort of recess exists on this side, which is all plough-land, in which stand the lower columns. On the south a beautiful olive-grove, rising in terrace above terrace, completely covers the sides of the hill, and a small extent of open terraced-land, for growing barley, exists towards the west and at the top.

The village itself is ill-built, and modern, with ruins of a Crusading church of Neby Yahyah (St. John the Baptist), towards the northwest”.

Part of map Sheet 11 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Other sections from their report is included in the text of this page.

Ancient Samaria in 1839 – view from the south

– illustrated by David Roberts – source: Library of Congress archive

- Modern Period (20th-21st century)

Two major archaeological excavations were conducted here: years 1908-1910 ( Harvard Expedition – directed by G. Schumacher and G.A. Reisner, assisted by C.S. Fisher and D.G. Lyon – see report); years 1931-1933 (British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Palestine Exploration Fund, and the Hebrew University – directed by J.W. Crowfoot and assisted by K. Kenyon, E.L. Sukenik, and G.M. Crowfoot).

Shomron is also associated with the history of the modern settlement: A pioneering group (“Garin Elon Moreh”), led by Menachem Felix and Benny Katzover, attempted to settle in the area of Shechem during the 1970s. After 8 futile attempts, the group tried in 1975 to settle in the area of Sebastia – in the old rail station near the ruins of Shomron. They were forced out of the site, but allowed to stay in the army camp of Kadum, south of Sebastia.

An Arab village of Sebastia is located on the eastern foothills of the ancient city. Since the area is under Palestinian control, Israeli tourists can visit the site only with protection of the Army, who coordinates periodic visits at the site.

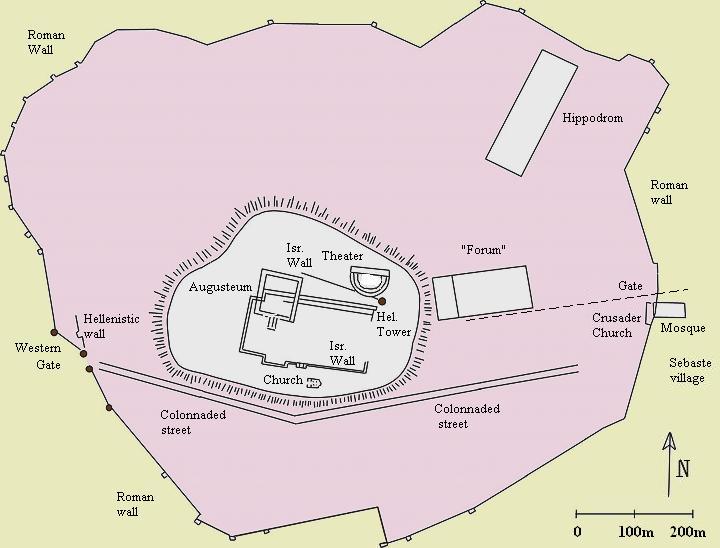

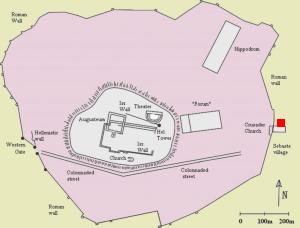

Structure:

The plan of the ancient city is shown in the following illustration. You can press on the places of interests to scroll down into the relevant section in this page.

From the Israelite period of Shomron/Samaria remained sections of Ahab’s palace and walls around the acropolis (marked as “Isr. Wall”).

Most of the antiquities found in Sebastia are remains of the Herodian city: the Forum; an Augusteum; the west city gate and colonnaded street on the south; Roman theater; a stadium; Temple to Kore (“queen of the underworld”) on a terrace north of the acropolis; 4km long city wall around the city; and the aqueduct which transported water from the springs east of Samaria.

From the Byzantine period are remains of a Church on the south side of the acropolis, while another Church on the east side is dated to the Crusaders period.

The Arab village of Sebaste is located on the eastern side of the hill. Some houses and restaurants are built inside the eastern section of the ancient city.

Photos:

(a) West Gate:

Remains of the Roman city walls and the west gate are visible after ascending the hill. This section is marked on the map as a red square.

A number of round towers protected the gate. The base of the north tower is seen in the photo, and the modern road passes to the right of it. A section of the south tower is located behind the tree on the right.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

Josephus wrote about the construction of the walls (Ant. 15 Chp. 8 5):

“And when he went about building the wall of Samaria, he contrived to bring thither many of those that had been assisting to him in his wars, and many of the people in that neighborhood also, whom he made fellow citizens with the rest. This he did out of an ambitious desire of building a temple, and out of a desire to make the city more eminent than it had been before; but principally because he contrived that it might at once be for his own security, and a monument of his magnificence. He also changed its name, and called it Sebaste. Moreover, he parted the adjoining country, which was excellent in its kind, among the inhabitants of Samaria, that they might be in a happy condition, upon their first coming to inhabit. Besides all which, he encompassed the city with a wall of great strength, and made use of the acclivity of the place for making its fortifications stronger; nor was the compass of the place made now so small as it had been before, but was such as rendered it not inferior to the most famous cities; for it was twenty furlongs in circumference. Now within, and about the middle of it, he built a sacred place, of a furlong and a half [in circuit], and adorned it with all sorts of decorations, and therein erected a temple, which was illustrious on account of both its largeness and beauty. And as to the several parts of the city, he adorned them with decorations of all sorts also; and as to what was necessary to provide for his own security, he made the walls very strong for that purpose, and made it for the greatest part a citadel; and as to the elegance of the building, it was taken care of also, that he might leave monuments of the fineness of his taste, and of his beneficence, to future ages”.

Under and to the sides of the north tower are traces of earlier walls and towers – Israelite, Post-Israelite, Hellenistic, Pre-Herodian and Roman periods.

A plan of the gate area was drawn by the Harvard expedition (Plan 10, page seq 518, text on pp 56-57). The orange colored structures are Roman (Herodian), while the other colors are dated to earlier periods.

Plan of the west gate area (Harvard expedition 1908-1910)

Below – a detail of the “angel” tower west of the gate.

Excavations of the gate area led the excavators to conclude that from the 5th century BC to the 1st, Samaria was a prosperous city, surrounded by a strong wall. Evidence of the Hasmonean destruction at 107BC was also found in this section, as well as on the summit of the hill.

(b) Colonnaded Street :

The Roman colonnaded street of Samaria is a famous landmark. The street connected the west gate (as above) to the east gate (now gone). This section is marked on the map as a red square.

The street, 12.5m wide, is about 1Km long.

The excavators found 600 monolithic columns, some of them still standing as seen in the following photos. Each column is monolithic – meaning formed of a single large block of stone.

Behind the columns were shops and structures.

The SWP report of 1872 and 1875 (Vol 2, pp211-214) described the status of the Colonnaded street at the 19th C, which at that time was in a better shape:

“The Colonnade appears to have surrounded the hill with a cloister not unlike that of the Temple at Jerusalem, situate on a level terrace with a higher knoll rising in the middle. The remains are most perfect on the south, where some eighty columns are standing ; the width of the cloister was 60 feet, the pillars 16 feet high, 2 feet diameter, and about 6 feet apart.

On the south it extended about 32 chains, or 2,100 feet, and remains of a gate were pointed out, and rude rock cuttings in the south-west corner, apparently the foundations of two gate towers. Josephus (Ant. xv. 8) makes the circumference 20 furlongs, or more than 10,000 feet. The real circuit is probably some 6,000 feet, so that the estimate is nearly double the actual length. The columns are principally monolithic. There are others, also without capitals, on the north-east of the hill, near the village, in a line running north and south, where also there seems to have been a gate. The present threshing-floor is close to them”.

Grand colonnade, Samaria between 1898 and 1946

Matson collection, Library of Congress

A detailed description continued (pp 208-209):

“The long rows of columns appearing above the surface at intervals along the whole south side of the hill have always been a feature of the site. They were rightly supposed to form part of the great colonnaded street built by Herod, which ran on a gradual upward slope along the southern side of the hill, passed around the eastern end, and so entered the Forum from the east. There is no evidence that the street continued all around the hill…. They gave the width of the central roadway as approximately 16 m. between centres of columns, while the width of colonnade along the south side was 6.9 m. The columns were monoliths, and were placed 3.26 m. from centre to centre. They were 4.7 m. high, the lower diameter 61 cm. and the upper 56.5 cm. The bases were of the usual Attic type, with deeply cut molding, like those of the Herodian temple. They rested on a curbing of slabs, 38 cm. thick, below which was a rough rubble footing….”.

(c) Forum:

The Roman forum in general was a public square in the civic center. It was reserved primarily as a marketplace and also as a social gathering place.

In Samaria, the Forum’s open space is now used as the visitors’ parking lot (see below), and only the basilica on its west side remained in relative good condition.

The Forum’s basilica is marked on the map as a red square.

The Harvard excavation report described the Forum (p211-212):

“The site selected for the civic centre of the Herodian city was a large, fairly level, natural terrace to the east of the summit of the hill . The actual area of the Forum corresponded very closely to that covered by the threshing floor of the modern Arab village . Its level was 26.5 m. below the court of the great temple, and 19.7 m. above the threshold of the west gate of the city. Along the north side of this area was built a heavy retaining wall, extending towards the west beyond the Basilica. This wall was traced for 161 metres. Smaller walls were built along the east and south sides. These were carried down through the earlier strata in construction trenches, the difference between the previous level and the new one being filled in with debris. “.

“The Forum was 72.5 m wide at the eastern end and 128 m. long on the north. … It was surrounded on all sides by a colonnade ca. 6m. wide. On the north this probably was open to the exterior, as well as towards the Forum, so as to afford a view over the city, with the Hippodrome below. On the west it was backed by the Basilica, while the south and east may have been enclosed by a solid wall, to screen it from the adjacent buildings. There were probably entrances on the east and south, the former giving access from the Street of Columns, which ran from the west gate, swept around the eastern end of the hill, and so came up to the eastern end of the Forum”.

- The Basilica:

The Basilica, on the western edge of the forum, was “a rectangular building, 32.6 m. wide and 68 m. long over its foundations”.

Harvard report described the western edge of the forum, where the basilica is located (p 212):

“Only the western colonnade has been excavated, the rest of the Forum being buried under a thin layer of debris. At the west end this debris was 1.5 m. deep, and sloped down towards the east, so that parts of the pavement of the eastern colonnade appeared on the surface. The central open space was unpaved, that is, it had the usual beaten earth floor. The colonnades, however, were paved with slabs of limestone, which, owing to their nearness to the surface, had mostly been removed by stone thieves. To get them out, many of the pedestals had been overturned or displaced. It was only where pedestals remained in situ over the original pavement that details of the construction could be obtained”.

“The west colonnade had a slight slope downwards towards the north. Originally along this short side of the Forum there were 24 columns, and seven of these have always been visible, their faces much weathered and decayed by exposure. Others were broken off below the modern surface, but still approximately in position with their pedestals, while the remainder were represented by pedestals and a few bases, mostly moved out of position. The spacing was 2.5 m. from centre to centre of the columns, except at the middle of the west side, where a space was left 4.38 m. wide, as an effective entrance to the Basilica, the east doorway of which was opposite this point”.

Around the basilica are monolithic columns, standing on pedestals. Harvard report provided details on the columns and pedestals (p215):

“The pedestals of the Basilica rested, as in the Forum colonnades, on a curbing of well-dressed and fitted blocks, 1.35 m. long and averaging ca. 70 cm. wide. The columns were ca. 3.88 m. on centres. The pedestals were 108 cm. square and 76 cm. high, although these dimensions varied slightly. … It will be seen that the moldings, where finished, are uniform in contour, varying only in height. The pedestal N1 was lower, and finished with plain bevels only, in place of moldings. It belonged to the restoration period, when apparently the plan of the northern end of the building was changed. “.

“The columns varied from 5.93 m. to 6.03 m. in height. These differences, with those of the pedestals, make the tops somewhat uneven, but not seriously so, and the inequality was probably adjusted by the capitals. The lower diameter of the columns was 73.5 cm., and the upper 66.5 cm. “.

One of the capitals is shown in the next picture.

“The capitals were Corinthian. Two almost perfect specimens were found in the debris . The leaves were well modeled and cut. The height of the best specimen, found in the eastern aisle, was 90 cm., and the spread of the abacus 1.15 m. In the debris of the west aisle was a fine capital 57 cm. high, fitting a pilaster whose top diameter was 59 cm. There were two rows of acanthus leaves, the lower row 31 cm. high, the second 23 cm.”.

The report on the basilica continues (p 214):

“The interior of the building consisted of a large central hall, 14.92 m. wide, and ca. 44 m. long, with open colonnades or aisles on three sides. Of these, one complete column remained on the south, and six along the west, where there had originally been twelve. In the portion excavated, the pedestals of the other columns, extending to the beginning of the apse, were still in situ”.

The roofing of the central hall was (p. 218):

“The central hall probably had a clerestory, and was roofed with wooden trusses covered with tiles, and the side aisles with single pitch roofs. In the debris were a number of fragments of terra-cotta roofing tiles… They were of hard red ware, 40 cm. wide and ca. 55 cm. long, slightly concave on the under side, and with the side ridges as shown. With these were found the ridge tiles, many still containing the lime mortar with which they had been cemented in place”.

A soldier, who accompanied to the tour as part of the security measures, stands on the northwest corner of the basilica:

More on the basilica:

“The central hall had been paved with stone, while the side aisles were paved with plain white mosaic, with a narrow border of black near the edges. This mosaic was almost perfect along the west side and on the east as far as the north end of the hall. Opposite the door leading to the tribunal had been a small ornamental centre-piece in color, but this was badly damaged. Its shape was a cinquefoil outlined with red and black tesserae. The single column in situ at the north end belonged to the original building, but had been re-erected on a plain pedestal. The foundation wall below it, which extended the width of the central hall, seemed from its poorer construction to be also of the later period, but a row of columns must have existed here or farther north in the original building”.

The area to the west of the basilica is not yet excavated, and is buried under the soil. Hopefully, the excavations will be renewed soon and other sections of the city will be explored.

- The Tribunal:

An Apse on the northern section of the basilica is seen in the following picture. This was the place of the Tribunal – the seat or court of the justice.

The report on the building is as follows (p214):

“At the northern end was a semicircular tribunal, 4.4 m. in diameter It had four concentric seats with molded edges. The lowest seat was 32 cm. high and 33.5 cm. wide, including the molding. The second was 100 cm. high. Above this the series appeared to have been rebuilt, as the masonry is less well fitted. The old moldings, however, were retained. The moldings of the inner ends of the steps and nearly all those of the upper steps had been displaced, but in the neighboring debris were a number of fragments of contours and radii similar to those of the moldings which were in situ. Among the fragments was a large block which had formed the inner end of one of the steps, the molding returning down the outer edge. The facings of the steps were of fitted stones, and the space between them and the main walls was filled in with small rubble. The seats were built upon a pavement which was 1.48 m. below the aisles, and at the east and west were flights of steps leading to that level”.

“The steps on the west led from a door on to the long west aisle, which extended the full length of the building. The east aisle was similar, but all traces of any door and wall had been swept away. The steps belonged to a restoration, but occupied the position of the original steps, as the doorway apparently belonged to the first period. Across the south side was the finely molded base of a wall which must have served as a sort of balustrade, dividing the lower room from the main building, if the latter opened directly on to the tribunal. The floor was paved with large slabs, those inside he round portion being cut to radius, with a large semicircular slab in the centre. The exact centre was marked by the remains of an iron staple, to which had been attached a ring”.

- South side

On the south side of the basilica are remains of the Israelite period wall and gate.

Hippodrome:

Standing on the north side of the forum, you can see a large area where the hippodrome was located. The top of the columns are seen standing above the surface.

This section is marked on the map as a red square.

The SWP report of 1872 and 1875 (Vol 2, p 211) described the Hippodrome and a possible gate on the north east side:

“A street of similar columns leads up the flat slope of the hill on the north. This was possibly a hippodrome, or else an approach to the north-east gate, being directed on the north-east corner of the upper colonnade”.

The 1908-1910 Harvard excavation report (p 219):

“No excavation has so far been undertaken on the site of the building lying east of north of the Forum and ca. 74 m. below it, which is marked by a number of columns still showing above the surface (Plan 1). The building occupies a long narrow depression in the side of the hill. The steep, sloping sides and end of this depression were utilized for the seats. The area enclosed by the rows of columns was 55 m. wide and 225 m. long. The south end, to judge from the contour of the present debris and hill, was semicircular, while the north end was square and open, being near and parallel to the probable line of the city wall. The columns were monoliths, and of the same shape as those of the roadway and in the other buildings. Farther towards the west, on a similar level, north of the temple, the side of the hill has a large, semicircular indentation, ca. 75 m. across. This likewise was open towards the north, and in the slope of the hill behind it was an outcrop of well-dressed masonry. This spot seems the most likely location for the Theatre, which must have formed one of the features of the Roman city”.

The Hippodrome was later excavated in 1932.

Theater:

A Roman theater is located to the west of the forum. It is dated to the 2nd or 3rd century AD.

This section is marked on the map as a red square.

The diameter of the theater is 65m. Some of its marble and rock-hewn seats are original, as well as parts of the stage.

The theater had 24 rows.

View towards the west:

View towards the north:

(d) Israelite and Hellenistic walls:

Behind the theater’s upper row are remains of the Israelite and Hellenistic walls. The picture below shows a section of the Israelite wall.

Another view of the rear of the theater, with the Israelite wall and the Hellenistic tower behind it.

A section of the Hellenistic wall (left) and Israelite wall (right). Above is a trail that leads to the temple on the summit of the hill.

The Hellenistic tower, seen in the following picture, was built into the older Israelite wall. Such towers were built around the acropolis of the city.

(e) Augusteum Temple:

A grand temple is located on the summit of the hill. It was built by Herod the Great on top of the earlier levels of the Israelite and Hellenistic periods. This section is marked on the map as a red square.

The remains of the temple seen today in the site includes a large stairway on the northern side of the temple – seen in the photo below – and sections of the Portico (porch leading to the entrance of the building).

The temple of Augustus (“Augusteum”) was constructed in ~16BC by Herod the Great, as a gratitude to Caesar Augustus, who gave Herod territories as a present.

Josephus writes about the construction (Wars 1 21 2):

“…and in the midst of this city, thus built, had erected a very large temple to Caesar, and had laid round about it a portion of sacred land of three furlongs and a half, he called the city Sebaste, from Sebastus, or Augustus, and settled the affairs of the city after a most regular manner.”.

The present remains are dated to the time of Septimius Severus (193-211 AD). This Caesar established the city as a colony in 201AD (“Colonia Lucia Septimia Sebaste”) and reconstructed the city, without major changes from the Herodian city. The restorations kept the original plans of the Herodian city and its buildings. The excavators determined that the Herodian temple fell into decay, and was actually used as a quarry (“Harvard Excavations at Samaria”, 1908-1910, pp. 47-48) . Severus restored the temple to its glory, and used some of its older stones during the restoration.

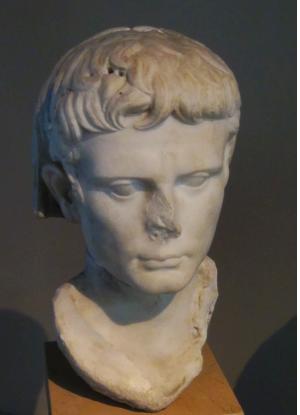

Bust of Augustus Caesar (reign 27BC – 14 AD)

The temple consisted of a a raised platform (altar) on the north side in front of the temple, a stairway leading to the paved portico (porch), a vestibule (corridor), series of columns on the sides, and the cella (inner chamber of the temple).

A similar temple (Augusteum) was built in Banias, also by the grateful Herod. A reconstruction of that temple is shown here, which may had the same design of the temple in Samaria.

A second Augusteum was erected in Banias

On the west side and south sides of the temple were series of houses. The temple area stood in the midst of these houses, and the whole cluster was surrounded by a strong wall and a street.

An altar was located in front (north) of the stairway, seen here as a square base on the left side of the photo. Its base was made of light rubble, and is situated on the bedrock. The altar was located at the edge of a forecourt, a large (22m) plastered floor extending to the north of the temple. This was a Temenos – an area of a royal or holy precinct.

The altar is dated to the Herodian period and was re-used after the restoration. A large marble statue of the Roman emperor (Augustus) was found here in front of the temple, and stood on the portico or on a pedestal.

A plan of the temple area is detailed in the excavation report (“Harvard Excavations at Samaria”, 1908-1910, pp. 47-50) and a plan of the Severus period – the last construction level – is based on their report (page sequence 512).

Plan of the temple area, Severus period (Harvard expedition 1908-1910)

The area of the paved portico (porch) and vestibule (corridor), now mostly removed, is seen below. Under the paved portico was an earlier Herodian stairway.

The north side of the temple was located on top of the wall, seen here beyond the cavity. The wall itself, made of very fine masonry, lies on the bedrock, and was part of the Herodian temple.

On the west side was a platform, probably the base of a staircase leading to the second floor. To the west (right) was a large structure – the Atrium house. Along the western edge of the summit was a wall, with 3 towers in the center and two corners of the wall. On the south side of the temple was an Apsidal building (a structure with an apse on its south side). The structures and walls are dated to the Herodian period was were re-used in the Severan colony.

The picture below is a view of the south-western side of the temple area. The lower area behind the temple walls are dated to the Israelite period, since the Herodian and Severan structures were removed in order to explore the earlier periods and reach the bedrock.

Prior to the Herodian period – during the Hellenistic period and early Roman period – the area of the temple precinct consisted of houses. Their floor was 230 cm below the floor level of the temple, and they were built over terraces descending to the west. A number of streets crossed the area along the south-north axis. Their dating was not clear, but the excavators suggested that they were constructed just before or after the destruction by the Hasmonean King John Hyrcanus I, who captured and completely demolished it (107BC). A later date is also possible, when the Roman general Gabinius restored the city (58-57 BC). Herod later confiscated the area, cleared away the houses, and constructed the grand temple.

(e) Israelite period – Ahab’s and Omri’s Palaces:

On the summit of the hill are the remains of the Israelite palaces, dated to Omri and Ahab. They were the earliest structures on the site and were built over the bedrock. The palaces were of royal size and construction, and therefore is no doubt on their identification.

This section is marked on the map as a red square.

The palaces were constructed in two phases. According to the Harvard excavation team (19008-1910), the first palace (Omri, 882-869 BC) was built over a small raised platform, and is located on the eastern (upper right) side of the excavated area seen below.

During the second phase (Ahab, 869-850 BC) a casemate style wall was built around the Omri palace and expanded the total area. Remains of his palace are seen on the upper left side of the picture, where a number of rooms of his palace are seen.

The next picture is a view from the south. Omri’s palace is on the right side, while Ahab’s palace was built over it and extended to the western side on the left. The palaces suffered greatly when Herod constructed a temple above their ruins.

One of the structures excavated in Ahab’s palace is the Osorkon house, where a jar was found with cartouches of the Egyptian Pharaoh Osorkon II (reigned 872 – 832 BC). Ahab reigned before or in parallel to Osorkon (882-869BC).

The excavations at Samaria. Unearthing Ahab’s Palace

1908-1910, American Colony

Matson Collection, Library of Congress

The findings in Ahab’s palace were exciting: the excavators found in the rooms of the administration building on the west (left) side of the palace important findings dated to the period of Ahab: 63 ostraca (pieces of ceramics with writings), scarab, ivory and other artifacts dated to the period. North of the palace additional Phoenician ivory were found. The Bible may have referred to this (1 Kings 22 39):

“Now the rest of the acts of Ahab, and all that he did, and the ivory house which he made, and all the cities that he built, are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Israel?”.

The excavators have established that the Israelite city was destroyed by Sargon II in ~722BC. After the destruction, some of the structures were rebuilt, “presumably by the alien colonists whom the Assyrian kings deported”.

Two rock-cut caves were found on the stone wall on the right side of the picture. According to a scholar, these were the burial places of Omri and his son Ahab. These tomb chambers were found in room 12, and the Harvard report wrote that it was the most singular feature, but identified it as a cistern (p. 61): “The most singular feature about this inner part of the palace of Ahab was room 12 and the rock cave opening into it. The door from room 11 into room 12 was so carefully blocked with masonry like that of the adjacent walls that it did not appear at first glance. On the inside of room 12 this door-block was left rough; that is, it had been built up from the side of room 11, and left closed, thus making of 12 a walled-up room. From room 12 a trench, a long cut in the rock, roofed with stone slabs to form a tunnel only about 80 cm. high, led into a great square rock-cut chamber (SI cistern 7)”. If indeed these are the royal tombs, this would be an important finding for Biblical Archaeology.

According to the suggestion by I. Finkelstein (2011), the area of the Israelite palaces covered a larger area. The palace of Omri was based on a large lower city (80 Dunam: 450m west-east by 230 south-north), and an upper city (30 Dunam) which was the royal podium. Both lower and upper platforms were man-made, using walls and an earth fill. The lower platform was protected by fortifications and possibly a moat on the south and east sides.

(f) St. John the Baptist Church:

This small basilica was constructed in the 5th century, and dedicated to John the Baptist. According to a Byzantine era tradition, this is where John ‘s head is buried. The church was repaired during the 12th century.

The church is located to the south of the acropolis, where according to the tradition was the prison where John was held in custody and beheaded. It is marked on the map as a red square.

The church was excavated by J. Crowfoot in 1932.

The western and northern walls and the altar on the east side are still standing, as seen in the photo below.

A view from the western entrance to the church is seen below.

The Southern narthex:

The northern Narthex:

The main altar is on the east side:

On the north-east side of the church is the crypt.

The crypt serves even today as a praying place.

A closer view of the crypt. The walls are plastered and used to have Fresco paintings.

A corner of the north-eastern side of the church:

(f) Crusaders Church:

Another church, dated to the Crusader’s period, is located on the east side (marked on the map as a red square). Most of its ruins are under the mosque of Sebaste.

The SWP report added important information – the church was located at the location of the Roman eastern gate, where another section of colonnaded street connects it to the forum (Vol2, p214): “The church is on the site of an old city gate, from which the street of columns started and ran round the hill eastwards”.

The SWP reports about it (Vol2, pp 212-3):

“The Church, a fine Crusading structure, over the traditional place of burial of St. John Baptist, is supposed to have been erected between 1150 and 1180 AD. It is now a mere shell, the greater part of the roof and aisle piers gone, and over the crypt a modern kubbeh has been built. The interior length is 158 feet, the breadth 74 feet ; the west wall is 10 feet thick, the north wall 8 feet, the south wall 4 feet. There were six bays, of which the second from the east is larger, probably once supporting a dome. On the east are three apses to nave and aisles, the central apse is 30 feet in diameter, equal to the width of the nave. The piers had four columns attached, one each side ; on the west was a doorway and two windows ; on the south four windows remain, and on the north three. The nave had clerestory lights. The sixth bay is slightly narrower than the rest. The bearing is due east and west”.

Sebastiyeh (Samaria). Crusader Church of St. John

1898 and 1946

Matson Collection, Library of Congress

Their report continues:

“The capitals resemble those of French twelfth century churches, but the cornice above is of semi-classic style, like that of the Nablus gateway. A sort of fortress appears to have been attached to the church on the north, flanked by square towers. The tomb in the centre is a small rock-hewn chamber, reached by 31 steps, and here the graves of Elisha and Obadiah are also shown. The masonry of the church is beautifully fine and perfect ; the stones are of moderate size (about 1 1/2 feet high and 2 feet long), and are regularly dressed with a toothed instrument, but not always in the same direction. The masonry of the northern building is rougher, and drafted on the north wall. Between the south windows on the outside are buttresses 5 feet by 2 1/2 feet. The west door has a simple pointed arch, but the windows, though at a higher level, have round arches”.

Northern views. Church of St. John, interior [Samaria]

American Colony, 1900-1920

Matson Collection, Library of Congress

(g) Views of the area

The south side of the palaces and the Byzantine church are located at the southern edge of the summit. A trail takes the visitor back to the parking place located near the Forum. From here are great views of the area and the colonnaded street.

The settlement of Shavey Shomron (Hebrew: Samarian Returnees) is located close to Sebastia. It was established in 1977.

(h) Panorama:

A set of panoramic views, as seen from the top of the hill of Samaria, are shown in the following pictures. If you press on either one, a panoramic viewer will pop up. Using this flash-based panoramic viewer, you can move around and zoom in and out, and view the site in full screen mode.

To open the viewer, simply click on the photos below. It will open a new window, for each of the three views, after a minute or so.

West view from West Gate:

North view from Forum:

South view above colonnaded street:

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the place:

Shomron: Hebrew name of the city and the region. The city was named Shomron, based on the name of the owner, as described in the Bible (1 Kings 16 23-24): “Omri … bought the hill Samaria of Shemer for two talents of silver, and built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, after the name of Shemer, owner of the hill, Samaria”.

Samaria: Greek name of the city. Josephus Flavius (Ant. 8 Ch. 12 5): “in the city called Semareon, but named by the Greeks Samaria”.

Sebaste: As a gratitude to Augustus, Herod rebuilds the city of Samaria and renames it to Sebaste (a feminine form of Sebastos, Greek for Augustus).

Sebastyia, Sebustieh – Arabic name of the village on the eastern hillside of the city, which preserved the ancient name.

Links and References:

* External:

- Ancient coinage of Sebaste

- Midreshet Shomron – coordinates visits to the site

- John the Baptist church (pdf)

- Harvard expedition (1908-1910)

- Layout of Iron Age Samaria – Finkelstein 2011

- Old photos of Samaria (Library of Congress)

- A visit to Samaria (with section on Sebastia)

* Internal:

- Samaria region – gallery of sites

BibleWalks.com – bringing the Bible Alive!

Kida <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Samaria site—>>> Deir Qal’a

This page was last updated on Mar 30, 2023 (new overview)

Sponsored links: