Multi-period fortified city, situated on a high hill in the Northern Samaria region, identified as Roman Narbata.

Home > Sites > Samaria > el-Hamam

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Ground views

* Peripheral Wall

* Summit

* South

* North

* Lower cistern

* Upper cistern

* Nature

Biblical References

Etymology

Links

Overview:

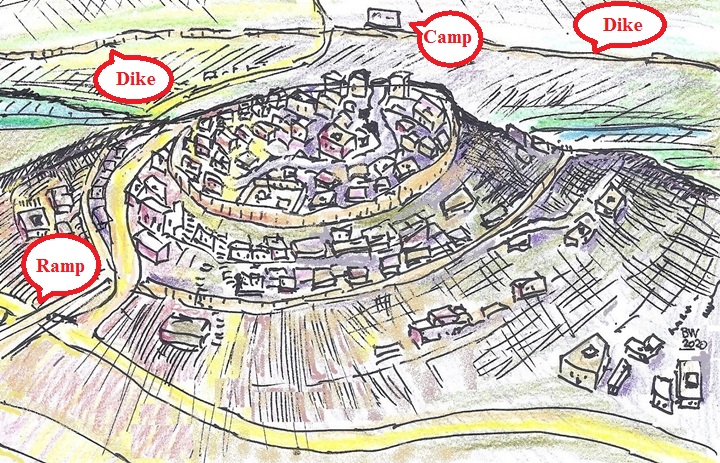

On Khirbet el-Hamam are ruins of a multi-period fortified city, situated on a high hill in the Northern Samaria region, 2km south east of Hermesh. Scholars identify it as Biblical Aruboth, Hasmonean city of Arbatta (1 Mac 5:21-23), and Roman Narbata of the great revolt. A Roman siege dike, camps and ramp were constructed around the city.

Map / Aerial View:

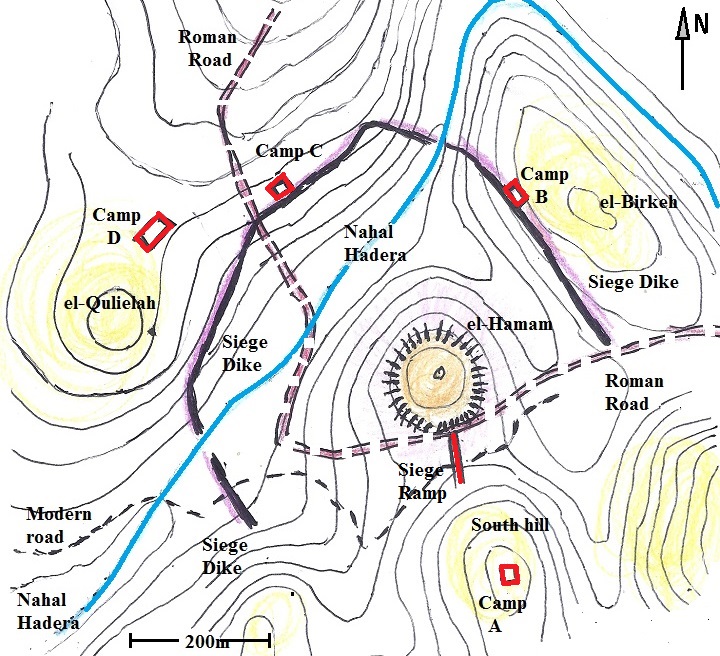

An aerial map is shown here, indicating the major points of interest around the site. Khirbet el-Hamam appears in the center of this map, at 247m above sea level, and 80m above the valleys around it. Around the site are remains of the great revolt against the Romans – a peripheral dike wall visible on the north and west sides, and Roman camps A-B-C-D.

History:

During its course of settlement, from the Iron Age until the early Roman period, the city served as a regional administration center. It is mentioned in the Bible and in Josephus Flavius books.

- Biblical periods (Bronze and Iron age)

The city in el-Hamam was established in the 11th or 10th century BC during the rule of the United Kingdom, and was fortified by a wide peripheral wall. The only findings of this phase of construction were this wall and ceramics. The archaeologists dated the ceramics starting from the Iron Age 1B (11th-10th century BC – 10%), followed by Iron age 2 (20%), Persian (30%) and Hellenistic (10%).

Scholars identify it as Biblical Aruboth (Iron Age 1B, 11th-10th century BC) of King Solomon’s 3rd province (1 Kings 4:7-10):

” And Solomon had twelve officers over all Israel, which provided victuals for the king and his household: each man his month in a year made provision…. And these are their names: … The son of Hesed, in Aruboth; to him pertained Sochoh, and all the land of Hepher”.

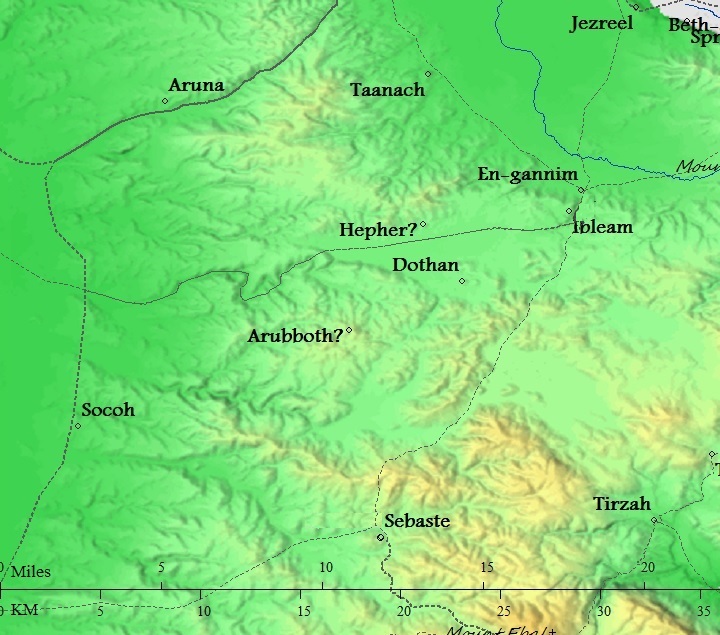

The cities and roads during the ancient periods, up to the Roman period, are indicated on the Biblical Map below. Aruboth (Arubboth) suggested location is marked in the middle of the map. It is located south of the main road (the “King’s road”) from Jezreel valley, via the valley of Dothan, towards the coast.

Map of the area around Kh. el-Hamam, marked as Arubboth

from the Canaanite/ Israelite periods to the Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

- Hellenistic/Hasmonean (3rd-1st century BC)

The second phase of major construction was in the Hellenistic period. A new wall was built around the summit. New structures and streets were built on the north hill and on the foothills beyond the fortified area. The city also expanded to the southern hill (el-Hamam ‘b’).

During this period the Hasmonean city was named Arbatta (1 Maccabees 5:21-23):

“Simon went into Galilee and fought many battles with the Gentiles. He defeated them and pursued them all the way to the city of Ptolemais, killing about 3,000 of them, and taking the loot. Then he took the Jews who were in Galilee and Arbatta, with their wives, their children, and all they owned, and brought them back to Judea with him. There was great rejoicing”.

-

Roman Period – (1st century BC – 4th century AD)

During the Roman period the city was named Narbata (Wars 2 14:5, 18:10). According to the ceramics survey, the majority of the pottery on the main hill was Early Roman (30%).

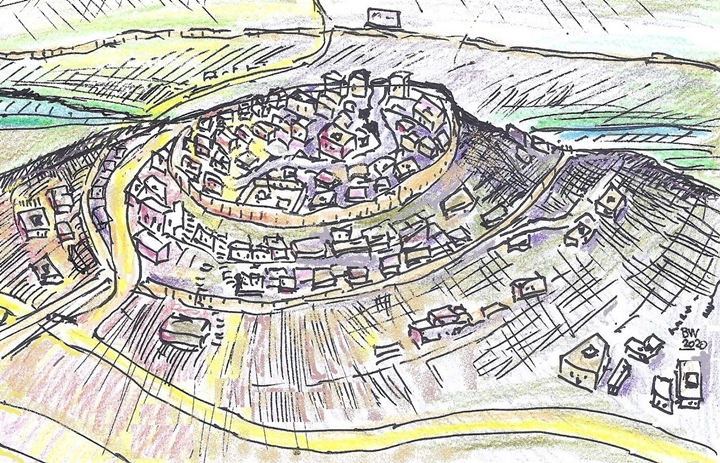

An illustration of the city, as seen from the north east, is shown here. The city at this time was centered on the summit of the northern fortified hill, protected by an upper Herodian wall and a lower Iron Age wall. All sides except for the south side, enjoyed a natural defense of steep foothills. A ring road ascended between the walls to a gate on the north side.

The tragic events that led to its demise enfolded in the Early Roman period. In the beginning of the great revolt against the Romans (66 AD), the zealots of Caesarea fled and hid in the city (Wars 2 14:5):

“…when he was overcome by the violence of the people of Cesarea, the Jews caught up their books of the law, and retired to Narbata, which was a place to them belonging, distant from Cesarea sixty furlongs”.

The Romans placed siege on the city, probably at the end of 66 AD, constructing perimeter walls with camps around it. This is the only siege complex north of Jerusalem. The other Roman siege walls were in Masada, Beitar and Michvar (Macherus).

Remains of the dike and the camps are seen around el-Hamam. They were dated to the 1st century AD.These are the Roman camps (also see the map below):

- Camp A is located on the top of the south hill.

- Camp B (23m x 23m) is located on el-Birkeh hill, adjacent to the siege dike.

- Camp C (13m x 15m) is located on the north west side near the dike.

- Camp D is larger (30m x 25m) located on a higher level on a ridge of el-Quleila, a hill west of the city.

The siege wall was 2.2m wide, located at a distance of 400-500m away from the mound. The length of the siege dike was 1516m, covering three quarters of the area around the city. It may have not been fully completed following an early surrender of the city.

A siege ramp was also constructed on the south side of the northern hill, ascending up to the first wall.

Illustration based on the Manasseh Hill country survey

Narbata was captured by Cestius Galus and demolished, although the details of this campaign were not provided. The tragic event was documented by Josephus, the commander turned historian at that time (Wars 2 18:10):

“In like manner Cestius sent also a considerable body of horsemen to the toparchy of Narbatene, that adjoined to Cesarea, who destroyed the country, and slew a great multitude of its people; they also plundered what they had, and burnt their villages”.

Narbata remained in ruins since the Roman period.

- Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

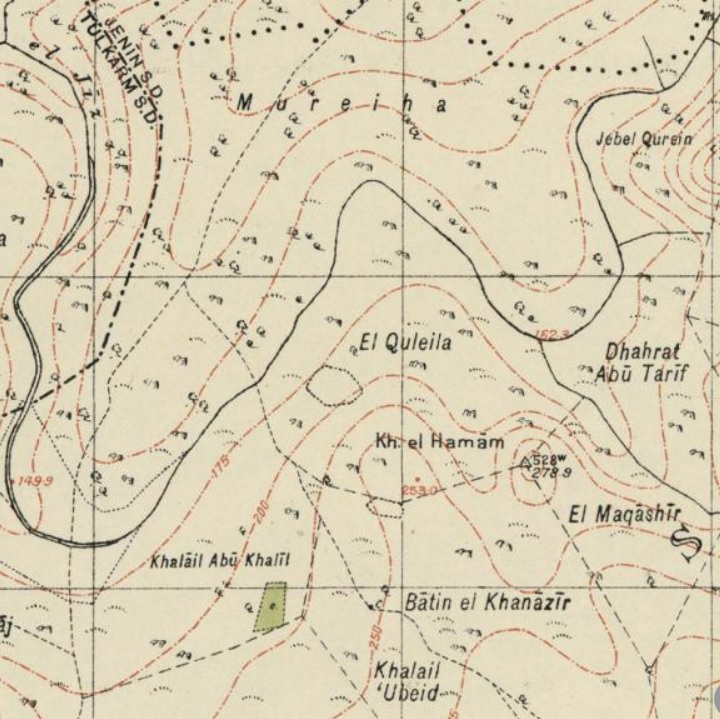

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. This map is part of sheets 8 and 11 of their survey results. The ruins are named “Tel el Khurba” meaning “mound of ruins”. It is located to the east of the Nahal Hadera valley, named here Wady el Ghamik (“the deep valley”). Nearby, on a hill northeast of the site, is Birket el Khurab (“the pool of ruins”). This was one of the Roman siege camps – camp B.

Part of map sheet 8 and 11 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

- British mandate

A map published in the 1940s names the site as Kh. el Hamam. The valley of Nahal Hadera is named Wadi el Jiz.

- Modern period

Narbata was lost for 2,000 years, and considered to be near Kibbutz Ma’anit, south west of the city of Harish. The name of the Ma’anit site appears on all modern names as Narbata. This name is also posted on a Highway 6 bridge south of Harish.

However, the Har Menasseh country survey by Adam Zertal and Nivi Mirkam (volume 3, pp. 327-332; 1978-1984) re-identified khirbet el-Hamam as Biblical Aruboth and Roman Narabta.

The northern hill was partially excavated in 1981 and 1984. The Roman camp B was excavated in 1980.

The place is within Area ‘A’ of the Palestinian Authority. Security limitations prevent Israelis to visit the site.

Photos:

The photos were taken on May 2020, under the supervision of Dr. Dvir Raviv who conducted a survey of the cisterns, and we thank him for joining his team.

(a) Aerial Views

A top view of the hill of Kh. el Hamam is seen here, captured by drone on May 2020, during an archaeological survey of the cisterns. The orientation is toward the south.

On the surface are several piles of white limestone, an indication of recent illicit digging.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The next views cover the surroundings of the site, starting from north and turning anti-clockwise.

North: The hill to the north of the site is named el-Birkeh (‘the pool’). On its foothill facing the site was one of the Roman siege camps (‘B’), built along the siege dike.

West: The valley of Hadera (Wadi el-Jiz) is located on the west side of kh. el Hamam. The Roman siege dike passed along the northern foothills, seen here as a straight line above the valley. Two siege camps were located near the dike wall (‘C’ and ‘D’).

South West: A south west view is seen below. Green patches of farming fields stretch along the valley of Nahal Hadera (Wady el Jiz). The Roman siege wall crossed the valley and was washed away.

South: The hill to the south of the site was also part of the city at the time it expanded to the south. Tombs were found on the northern hillside facing the northern hill. On top of the hill was probably one of the Roman camps (‘A’).

![]() The following video shows a view of the site and its surroundings, as capruterd by the drone. It starts over the south side, then turns to the west.

The following video shows a view of the site and its surroundings, as capruterd by the drone. It starts over the south side, then turns to the west.

(b) Ground Views

The northern hill of el-Hamam is seen from the hill on the north (“el Birkeh”). Behind it is the southern hill of el-Hamam. The smoke between both hills was from a local fire set by a farmer to burn trash.

Another view is from the south west side. The entrance road to the city was from the south side, and it crawled up a ring road to the north side of the hill where the city gate was probably located.

(c) Peripheral wall

Around the hill are several lines of walls. The lowest visible wall can be seen on the south side of the hill.

During the Iron Age, a 3m wide wall was built around the lower side of the hill. It was built of large hewn stones standing above the natural cliff at the sides of the hill.

Later, during the Late Hellenistic period, another 2m wide wall was constructed at a higher level, with 5m gap between the wall and the Iron Age wall. This inner wall formed a 20 dunam acropolis on the summit.

The gap between the walls formed a base of the ring road that started from the south west side, surrounded the hill, ascending to a gate on the north side.

(d) Summit

The summit is heavily covered by ruins of structures. Their dating starts from the late Hellenistic period, and continues until the great revolt (66 to 70 AD) when is was abandoned. Among the ruins are ~50 cisterns, some of which were examined during the survey.

During our survey visit in May 2020, the weeds covered the entire hill, thanks to the unusual wet winter. Two soldiers accompanied us during this visit in order to boost the safety of the survey team.

Although the weeds made it hard to identify structures, there were areas with some visibility.

On the summit we noticed a base of a wall, as seen in the photo below. Note that each bar on the archaeological measuring stick is 10cm long.

Previous surveyors reported on a central structure, 8m by 10m, built with Hellenistic style hewn stones. To its west they unearthed a residential area with a street that descended to the city wall. Adjacent, they excavated two residential quarters, the southern one with a plan of a courtyard surrounded by rooms. They dated the structures to the Late Hellenistic period, which was in use until the great revolt.

The hill is covered with Late Hellenistic and Early Roman ceramics, such as this segment.

(e) South side – Siege ramp

The Romans placed a tight siege on the city, constructing a dike and camps around the city. A common tactic to penetrate the walls was to raise a ramp on the weakest side of the fortified city, sending in the troops along the ramp.

On the south side of the city, facing the southern hill, is a raised ground that is now covered by an orchard. This may have been the base of a siege ramp. It is 130m long and 4.5m wide, constructed of a ground fill between two walls raising 1m above the ridge.

The assumption is that it was built during the Roman siege, reaching to the level of the city wall. It did not penetrate the wall, so it may be assumed that the defenders surrendered before the final onslaught.

Another theory suggests that the ramp followed the line of a siphon type aqueduct that filled up the cisterns from a remote southern spring.

A section of the siege ramp and the defense walls was examined in the 1984 excavation. A 10m wide cut started from the siege wall, reaching the entrance ring road and the Iron Age wall.

To the east of the Iron Age wall the excavators identified a wide public structure, 30m by 25m, that was located outside the Hellenistic period city. It was not yet excavated, and its purpose was not yet established.

Another view of the south side is in the next photo, capturing the shepherd leading the herd down to the valley.

(f) Northern foothills

The northern side of the city faces the hill named el-Birkeh. Along the foothills on that hill are remains of a siege wall, and one of the Roman camps. The wall is seen here as a straight line on the foothill.

Notice in the bottom of the above photo is a large stone on the hill side – a crushing base of an oil press. It is shown in detail below.

Another element, seen across the valley, is a round group of stones. It is built just above the siege wall. This is an ancient lime kiln, used used to prepare plaster, in order to seal the walls of cisterns and structures.

(g) Lower cisterns

On the northern foothill, at a lower level below the iron age wall, are 3 large cisterns that supplied water year round. They were fed by run off rain waters, and according to one theory they may have been fed by an aqueduct.Their capacity held 800 to 1000 cubic meters of water.

A top view captured by the drone shows the entrances to the cisterns.

An entrance to one of the cisterns, located on the northern foothill, is seen below.

Dvir Raviv selected another cistern to explore and map it. Using a metal ladder, we descended into that cistern.

Stepping down the ladder, we entered inside the cistern. Parts of its cavity was filled up with soil that accumulated over the years.

Inside the cistern: we mapped the cistern, checked the walls, dated the plaster, and searched for escape tunnels. We were surprised to find new illicit diggings into the bottom of the eastern wall, but leading to a dead end.

The top entrance to the cistern is seen on the ceiling.

The same hole is seen from the top side. The water was extracted from this entrance by lowering a bucket into the cistern. The extraction of the water may have been accomplished with a mechanical device (pully and rope) to raise the water into the city.

(h) Upper cistern

On the summit was another cistern we explored. This one has a larger entrance on the surface.

A drone view shows the cistern from the top side.

A narrow entrance to a hiding tunnel is located at the bottom of the cistern.

Yoram is seen here peeking into the entrance of the tunnel, but did not take the challenge to enter inside.

The team explored the plan of the tunnel.

(i) Nature

Except for the large amount of weed and thorns, there are some colorful wild flowers seen on the foothills. This perennial name is Syrian Cantip (Nepeta curviflora, Hebrew: Nepit Kefufa). It is known for its medical properties.

The bush in the next photo is called “Splendid Bindweed” (Hebrew: Khavalval-Hasi’akh, Scientific: Convolvulus dorycnium). It flowers between April and July (the picture was taken in late May).

Biblical References:

1 Kings 4: 7-10

Scholars identify Kh. el Hamam as Biblical Aruboth (Iron Age 1B, 11th-10th century BC) of King Solomon’s 3rd province:

” And Solomon had twelve officers over all Israel, which provided victuals for the king and his household: each man his month in a year made provision…. And these are their names: … The son of Hesed, in Aruboth; to him pertained Sochoh, and all the land of Hepher”.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- Aruboth – Biblical city (Iron Age 1B, 11th-10th century BC); King Solomon’s 3rd province

- Arbatta – name of the Hasmonean city (1 Maccabees 5:21-23):

- Narbata – name during the early Roman period (Wars 2 14:5)

Links:

* External links and references:

- “The Menasseh hill country survey” – volume 3 pp. 327-332 [Adam Zertal – Nivi Mirkam, 2000]

- “The new encyclopedia of archaeological excavations in the Holy Land” [1992 E. Stern editor, Volume 2 pp. 499-502]

* Internal Links:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- Wild flowers of the Holy Land

- Hiding Complexes info page

BibleWalks.com – walks along the Bible land

Deir Samaan <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next site—>>> Ferasin

This page was last updated on June 3, 2020 (added illustrations)

Sponsored Links: