Remains of a multi period settlement situated on a Kurkar sandstone cliff, and a Crusader fortress.

* Site of the Month July 2018 *

Home > Sites > Sharon > Apollonia (Arsur, Arsuf)

Contents:

Overview

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Crusader period findings

* Moat

* Bridge

* Castle

* The Keep

* Kitchen

* Outer fortifications

* Cliff

* Southern rooms

* Harbour

* Display

* Dwellings

* City Walls

* Other Periods

* Area C

* Byzantine period

* Roman period

* Cistern and Kiln

Etymology

Links

Overview:

A remarkable national park, with remains of a multi period settlement situated on a Kurkar sandstone cliff, and a Crusader fortress.

Location:

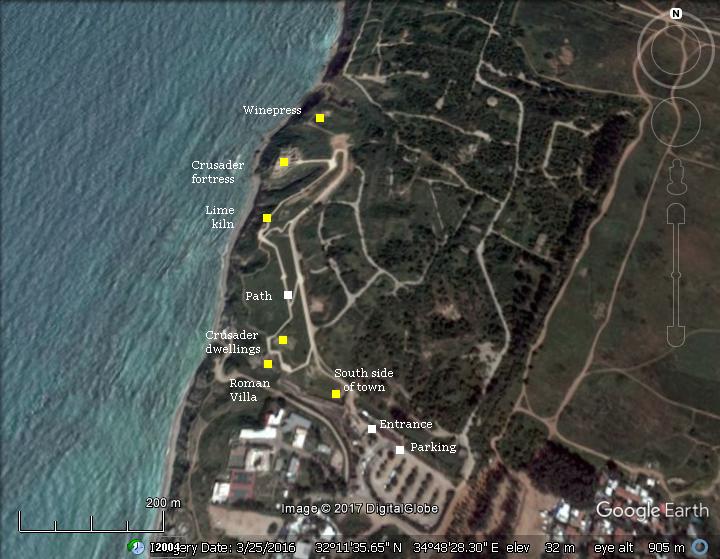

Apollonia is situated on a Kurkar sandstone cliff northwest of Herzliya. The ridge is 35m above the sea of the Mediterranean.

Most of the ruins of the town are yet covered, except for selected excavation areas and the Crusader fortress.

After entering the park’s entrance on the south side of the ancient town, the path leads north towards the Crusader fortress which is the highlight of the park.

History

-

Persian period (586-332 BC), Hellenistic period (332-63 BC)

The site, a remarkable national park, includes ruins of settlements starting from the Persian period (Phoenician port of Reshef or Arshaf), followed by a Hellenistic city in the 3rd century BC (named Apollonia).

It then was captured and settled by the Hasmoneans (80-57 BC), as per Josephus (Ant 13, 15:4): “Now at this time the Jews were in possession of the following cities that had belonged to the Syrians, and Idumeans, and Phoenicians: At the sea-side, Strato’s Tower, Apollonia, Joppa, Jamhis, Ashdod, Gaza, Anthedon, Raphia, and Rhinocolura”.

-

Roman (63 BC-324 AD), Byzantine period (324-638 AD)

The Romans, headed by Pompey the Great, conquered the land in 63 BC. Pompey and later Gabinius (the governor of Syria) stripped the coastal cities from the Hasmonean kingdom. Apollonia, as other coastal cities, became an autonomous city reporting to the governor of Syria. (Ant 14 4:4): “…the maritime cities… All these Pompey left in a state of freedom, and joined them to the province of Syria”. Gabinius resettled the city (Wars 1: 8: 4): “Gabinius, leaving forces to take the citadel, went away himself, and settled the cities that had not been demolished, and rebuilt those that had been destroyed. Accordingly, upon his injunctions, the following cities were restored: Scythopolis, and Samaria, and Anthedon, and Apollonia, and Jamnia, and Raphia, and Mariassa, and Adoreus, and Gamala, and Ashdod, and many others”.

During the Byzantine period the city, renamed Suzussa (“city of the Saviour”), flourished and grew to an area of 280 Dunam (70 acres). A Samaritan community, and perhaps also a Jewish community, was present in the city.

The Peutinger Map (Tabula Peutingeriana) is a medieval map which was based on a 4th century Roman military road map. The map shows the major roads, with indication of the cities, and geographic highlights (lakes, rivers, mountains, seas). Along the links are stations and distance in Roman miles (about 1.5KM per mile).

In the section shown below is the center area of the Holy Land, drawn in a rotated direction (Egypt on the left, the Mediterranean sea on the top, and Syria on the right). The major cities are (from left to right): Jerusalem listed as “Helya Capitolina formely Herusalem” (drawn as a double house, Jaffa as “Joppe”, Caesarea Maritama as “Cesaria”. The roads are shown as brown lines between the cities and stations.

Apollonia (“Appolloniade”) is a major station along the way of the Sea (Via Maris), XXII (22) Roman miles from Caesarea, and XII (12) Roman miles from Jaffa.

A section of the Peutinger map, with Apollonia in the upper middle location on Via Maris

-

Early Arab period (638 -1099 AD)

The Arabs captured and settled here (7th-11th century) renaming the city Arsuf. During this Early Arab period the city shrank to 90 Dunam (22 acres), and a strong new wall fortified the area of the city.

-

Crusaders (1099 -1291 AD)

In 1101 Arsuf fell to the Crusaders, who renamed it Arsour. The Muslim residents were expelled from the fortified town. The strategic location of the port town – along the coastal road and only 2 days sailing time to Cypress – was an important Crusader asset. In the 1160s it became a Frankish center of the southern Sharon plain seigneur, under lord Johannes de Arsur .

After the 1187 Crusader defeat in Horns of Hittim, Arsour was lost to Saladin’s Ayyubid Arab forces during 1187-1191. Saladin dismantled the city walls in the wake of the third Crusade.

Arsour/Arsuf was then recaptured by Richard the Lionheart after the battle of Arsuf (1191). An illustration of the battle is seen here. The subsequent treaty of 1192 between Richard and Saladin gave the town back to the Crusaders, but it was resettled only in the 1230’s.

Battle of Arsuf (1192) – illustration by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

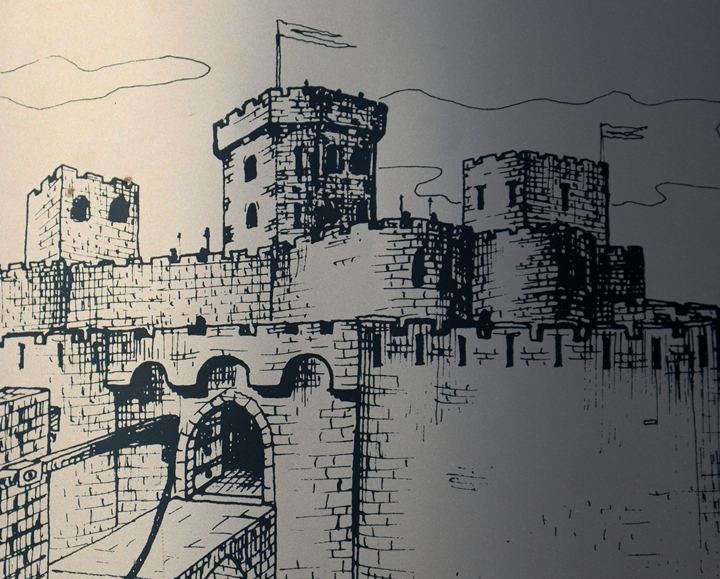

The fortress seen today was built in 1241 by Jean d’Ibelin d’Arsour, on top of the highest point of the Tel.

His seal is seen here. It features an armored knight on one side, and a castle on the other side.

Seal of Arsour (found in Malta).

The inscription on the left side reads: Ba(lian) d Ybel(in) s(eigneur) d Ars(ur) co(n)establ(e) dou reaume d(e) I(e)r(usa)l(e)m or: Balian of Ibelin, lord of Arsur, constable of the kingdom of Jerusalem.

The inscription on the other side reads: “Ce est le chastiau d Arsur” or: “this is the castle of Arsur”. Indeed, the illustration fits the plan of the fortress, with the inner gate protected by two corner towers and the keep behind it.

The fortress was later leased to the Hospitallers Knights in 1258. The fortress was then refortified in preparation to the Mameluke onslaught.

In 1265 the fortress was attacked by Mameluke forces headed by Bybars. It was defended by 2,000 warriors, but after 40 days of siege the city walls were breached and the Crusaders retreated to the castle. After 3 more days , the fortress fell. The surviving defenders were forced to take part of the demolishing of the city and the castle, then were taken to slavery.

-

Late Arab period (1291-1516 AD)

The town was in ruins since the Mameluke conquest. In the end of the 16th century the Arabs returned to the area 0.5km south of Arsour – in the village of el-Haram (el-Haram ‘Aly Ibn ‘Aleim) where the mosque of near Sidna Ali is located. Ali was an Arab general in the 11th century. The mosque was built by the Mamelukes in 1481. In earlier periods this place was holy to the Samaritans, who regarded the tomb to be of the Biblical prophet Eli – the high priest of Shiloh .

-

Ottoman period (1516-1917 AD):

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) in 1873. A section of the survey’s map, part of Sheet 10, is shown here. Note the ancient road, part of the way of the Sea (Via Maris), traversing the ridge on the east side of Arsuf.

Part of map Sheet 10 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Their report of 1873 in Sheet X (Volume 2, pp. 137-138) was:

“The remains of the Crusading town, with its inner fort and harbour, were surveyed in May, 1874, with a chain and compass. The total area included inside the ditch is 22 acres, or 660 feet by 1,452 feet. The form is irregular. The ditch has an average width of 40 feet, but on the south side it is rock-cut and 100 feet wide. Very little remains above the surface, and the site presents dusty mounds which cover the foundations. There are remains of a postern on the east, with projecting piers for a drawbridge ; on the south, close to the sea, is a spring, to which a small path leads down from a postern. A wall projects at right angles to the south wall, and enfilades the western part of the ditch, where it is deeper and wider. There are several cisterns near the western wall above the beach. The inner keep stands directly over the harbour in the north-west corner of the place, and has on that side a batter wall some 50 feet high ; remains of vaults are visible here also. The keep had a ditch round three sides about 100 feet wide, and a ramp and drawbridge communicated with the outer part of the fortress. The keep has an area of about half an acre. The level of the bottom of the fosse is about 50 feet above the beach. The harbour measured 100 yards north and south, by 40 yards east and west. A well-built jetty runs out on the south, and a narrow entrance is here made, behind a reef of rock, the entrance being barely 30 feet wide. The masonry at Arsuf resembles that at Ascalon. The work is, however, earlier than 1190 a.d”.

A map of the site is on page 137 (oriented to the west). Notice the 2 springs on the coast (marked on the map) – one on the south side of the city, and the other one inside the harbour on the north side.

Their report also includes a history of the site (Volume 2, pp. 137-138):

“The ancient history and Phoenician associations of Arsuf may be gathered from the following tract by M. Clermont-Ganneau. The name of Apollonia, it has been suggested, may have been conferred upon the city by Apollonius, son of Thraseas, who governed Coele Syria for Seleucus Antipater. It is mentioned by Josephus as one of the places which had formerly belonged to the Phoenicians. The Peutinger Tables give its position accurately as 22 miles from Caesarea. It was in ruins in the year 57 BC, when the Romans rebuilt it. It is then neglected by history for a thousand years, when we find it a fortified stronghold. Raymond of Toulouse besieged it, but failed to take it, and retired jealously, sending a message to the garrison that they need not be afraid of the King of Jerusalem. In fact, Godfrey met with so stubborn a resistance that he too had to raise the siege, and turned his arms in revenge upon Raymond. The place, however, was afterwards taken by Baldwin I., who gave the inhabitants permission to retire to Ascalon. Richard Coeur de Lion defeated Saladin beneath the walls of Arsuf in 1191, and regained the place. Louis IX. in 1251 restored the fortifications; but in 1265 the Sultan Bybars, after an obstinate defence, took the city, massacred the inhabitants, and destroyed the fortress and walls. Arsuf has since remained uninhabited”.

-

Modern period:

Excavations in Apollonia started in the 1990s and extended for 24 seasons: 1977-2004 (directed by I. Roll), 2006 (co-directed by Roll and O. Tal), and 2009-2015 (directed by O. Tal).

The site was opened to the public as a national park of Apollonia in 2002.

Photos:

(a) Aerial views

This aerial view of Apollonia is from the west side, 250m off the coast. The ruins extend across the whole length of sandstone ridge that overlooks the shoreline. The national park is about 1.5km long, with the park entrance on the south east side.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

A closer view of the Crusader castle is in the next aerial view. The castle is surrounded by a deep dry moat from three sides. Three systems of fortifications defended the castle, which was built in 1241 and destroyed 24 years later.

The outer gate to the Crusader city is located 300m south east of the castle, seen here in the far right side.

Another view of the fortress, this one from the south side. In the far background is the city of Netanyah.

![]() The following YouTube video shows a flight over the site:

The following YouTube video shows a flight over the site:

(b) The Crusader fortifications

The fortress is surrounded by a dry moat. The entrance was via a bridge above the moat on the south east side.

There are three systems of fortifications – outer defense layer (retaining wall above the moat, semicircular towers and gate), inner layer (18m high wall parallel to the outer fortifications), and a 10m high keep. The remains of the Crusader harbor are seen on the west side of the fortress.

(c) Crusader Moat

The dry moat that surrounded the fortress is 30m wide, 14m deep. It is bounded by an outer retaining wall, seen here on along the south side of the moat.

The next photo shows the northern side of the fortress, also with a deep moat and an outer retaining wall.

(d) Bridge

The entrance from the town into the castle was from the south east side. The access was by a wooden draw bridge, which was supported on the stone bases seen in the middle of the moat.

The bridge led to the retaining wall at a level lower than the castle. Then the street turned to the right and entered thru the inner gate on the east side.

(e) Crusader castle

This aerial view shows the inner plan of the concentric fortress. In the center of the fortress is a 28m long by 10m wide courtyard, surrounded by rooms.

A modern entrance leads to the inner gate. During the Crusader period this entrance did not exist, and the entrance was only through a draw bridge from the south east side.

The inner gate of the fortress, on the east side, was two story high, with a tower on each side. A heavy vertical sliding metal door, with two wooden doors behind it, secured the entrance.

The seal of Arsour illustrates the inner gate, the tower on each side, and the keep behind it.

Detail of the seal of Arsour

A placard of a Crusader knight protects the gate…

Notice the illustration on the shield: It has the seal of the order of the Hospitallers, with the Agnus Dei (image of the divine lamb – symbol of Jesus) and the inscription : “SIGILLVM S IOHANNIS +” meaning: “sign of John”. The Knights of this order named their order after John the Baptist, and were called the “Knights Hospitallers of St. John”, or commonly known as the Hospitallers.

A view from the top of the inner gate is in the following aerial view. On each side of the gate are towers.

The remains of the hall of the northern side tower is seen in the next photo. It is 5m x 12m, and its walls were covered with a white stucco.

Past the gate is a large courtyard in the center of the fortress, surrounded by rooms. This was the lower floor of the two story structure. Steps on the west side lead up to the second floor, and down to the 2 underground floors. The floors above and below the courtyard are now missing.

The courtyard, a layer of rough plaster, is 28m long and 10m wide.

This is a view from the courtyard toward the inner gate.

(f) The Crusader Keep

The Donjon (French) is called “the keep” (English) and “Bashura” (Arabic), which is a strong central tower which is used either as a tower, inner fortress or dungeon (hence the name Donjon). In medieval castles the Donjon was usually an inner tower which protected the defenders in case the main walls were penetrated, and in daily life it served as the residence of the commander of the fortress.

The keep of Arsour is located on the western side of the castle, beyond the courtyard. It has an octagon shape, and was 10m high. Now only the base of the tower remains after it was dismantled in 1265.

The tower was built over an arch, seen in this photo. On its remaining level is an observation point.

An illustration of the keep (center), the draw bridge gate, and the two side towers are illustrated on a sign of the national park.

(g) Kitchen and dining area

The kitchen is located on the north side of the courtyard. In the kitchen are five ovens, two plastered water pools, and a water channel.

The dining room is located on the northwest room, near the kitchen. The archaeologists discovered many clay bowls and decorated glazed pottery from the Crusader period. After all – “An army marches on its stomach…” (as per Napoleon Bonaparte and Frederick the Great).

Near the kitchen is a large storage installation, used for storage of grains and other food products. The installation is round, 3.3m in diameter, with a stone dome supported by dressed stones and covering the floor. On the floor are black basalt stones – formally grinding stones.

A round grinding installation is located on the north east side of the courtyard. It was used to grind grain for the kitchen.

The round grinding installation is seen better from the top. It is 3.4m in diameter. In its center was a round stone with a hole in the middle, which was the axis for a millstone.

(h) Outer fortifications

A great view of the coast line is seen from the northern side of the fortress.

A section of the outer fortifications can be seen at a lower level. This wall was part of a semicircular tower, constructed above the retaining wall above the inner side of the moat.

(i) Structures above the cliff

On the cliff above the harbour was a complex of subterranean halls. Their ruins are seen beyond the line of the castle. Most of the structures were damaged after the 1265 conquest, falling into the sea.

A vertical view from the east side, seen next, better shows these missing structures. The halls were aligned north-south.

A lone wall and traces of one of the rooms, just south of the keep, remained more or less standing, as seen in the following photo.

(j) South rooms

On the south side of the courtyard are two more rooms.

The south east room faced the bridge head and the south moat.

In this room is a collection of ballista stones that were shot from the fortress during the 1265 assault.

Another view of the ballista rocks is below. A total of 2,200 stones and numerous arrow heads were collected around the fortress.

On the south west room is another pile of ballista rocks.

On the walls of this room is an evidence of the great fire that burnt the fortress after it was captured.

(k) Crusader Harbour

The Crusaders built a harbour in front of the castle. There were two breakwater walls. The northern underwater wall is clearly visible here stretching diagonally outwards from the shore, while the base of the southern wall is facing the southern edge of the fortress. The harbour has a trapezoid shape, 80m in length (north to south) and 30m wide (east to west).

The northern breakwater is seen next. It is 40m long and 4.5m wide on the average. The ruins of a round tower, once measuring 12m in diameter, is located at its western end.

The next photo is another view of the harbour at the foot of the castle.

The Crusaders constructed a tunnel access from the shore into the castle. However, the location of this tunnel has not been yet discovered.

The maritime entrance to the harbour was on the south side. It was shallow – only 60cm of water above the reef during a medium tide. Therefore, this raised doubts about the function of the harbour. According to the maritime archaeologists, this small and shallow harbour was actually a military installation, probably used as a mooring basin used to service the ships.

A larger sheltered anchorage was found opposite the town, 200m south of this harbour, and at a distance of 60m from the shoreline. The archaeologists dated the underwater findings starting at the Persian period, with the majority of the Byzantine period.

(l) Display

Near the entrance to the fortress is a collection of marble columns, collected from the archaeological excavations.

Nearby are a number of models representing medieval military siege instruments (from front to rear): Ballista (bolt thrower), Catapult (ballistic device to throw rocks), trebuchet (swinging arm) and battering ram (breaching fortifications).

(m) Crusader dwellings – Area T

In this excavation area, on the south edge of the Crusader town, are a number of dwelling buildings.

They were first constructed in the Byzantine and Early Arab period. The structures were destroyed in the 12th century (after the Ayyubid conquest), then reconstructed after the return of the Crusaders. They were abandoned after the Mameluke conquest of 1265.

The plan of the buildings is based on a central courtyard surrounded by rooms.

(n) Crusader City wall – Area L

The Crusader fortress was constructed on the north west corner of the city. However, the entire city was much larger, which required to construct massive fortifications. During the Early Arab period the city (7th-11th century) a new wall was constructed around the area of the city. The Crusaders later reused the Arab city wall in order to protect the Crusader town.

A section of the wall is the south eastern corner, near the entrance to the national park (area ‘L’). This section was a Crusader corner tower, which was built on top of the Early Arab period wall. Below the walls are remains of Byzantine structures.

Other sections were unearthed in the western parts (areas ‘E’ and ‘H’).

(o) Other periods

Under the Medieval period layers there were structures, installations, tombs and other findings related to the earlier periods of occupation. The following sections review these earlier periods.

(p) Samaritan Wine press

A large Samaritan winepress dated to the 5th-6th century AD was unearthed north of the castle. It includes a large treading floor paved with mosaics, and a very large fermentation pit.

The treading floor is where the grapes are laid and crushed by the feet of the workers, extracting the juice. The juice, together with the crushed grapes, were left for preliminary fermentation. Use of shoes was avoided in order to prevent crushing the grape seeds, thus making the wine bitter.

The treading floor is 9.8m x 7.5m, and has a Greek inscription in its center. It reads: One only god, help / Cassianos together with wife / and children and everyone.

The secondary fermentation pit, 3m x 2.25m, is where the juice accumulated and underwent the secondary fermentation process. The pool is lower than the treading floor, so the juice flows down into the pool.

The winepress ceased to function in the 6th century, perhaps following the Samaritan revolt of 529 AD. It was damaged by the large earthquake of 749 AD.

(q) Area C

In this area, east of the lime kiln, is another area of excavation. The archaeologists unearthed a Byzantine period winepress complex, and Roman/Hellenistic burial jars and tombs on an earlier layer.

(r) Byzantine period

During the Byzantine period (5th-6th century AD) the port city flourished, spreading over 280 Dunam (28 hectares). It had agriculture installations used for exporting goods, as well as manufacturing glass.

One of the glass fragments were seen near the winepress. 12 glass furnaces were located in Apollonia and around it.

A section of the city wall, designated as area ‘E’, is the southern side of the wall that once surrounded the medieval city.

Near the entrance to the national park grounds, inside and adjacent to the medieval town walls (area ‘P1’), the archaeologists unearthed a section of a Samaritan synagogue. The room that was excavated was plastered, and has a trapezoid shape with an area of 6.5m x 7.5m. There is a semicircular plastered niche on its south side, and an opening on the north side. The room was dated to the Early Byzantine period.

A mosaic inscription, written in two languages, was found on this floor. It reads in Greek (in 5 rows of red stones, seen on the top of the photo below):

“One only god / who helps Gadiona / and Iulianus / and all who deserve it

The Samaritan script (in the lower row of black stones) reads: “possession in its place”.

On the southwestern side of the city a magnificent church was unearthed, dated to the 6th century AD.

(s) Roman Villa – Area E

Under the southern side of the Early Islamic city wall are remains of a Roman villa. Most of the structure is located outside of the wall.

This photo, looking towards the west side, has a clear view of the Roman structure. The building is 24m by 21.5m, built on a platform that was cut into the sandstone rock. The plan of the villa was a central courtyard surrounded by rooms. This peristyle courtyard (6.45 x 3.85m) was an internal garden surrounded by square columns, as seen on the left side. A long corridor, seen in the center of the photo, crosses the south side of the courtyard from east to west, opening the structure to face the sea.

(t) Cistern and Lime Kiln

Water supply was based on rock-cut cisterns and water pools that stored the runoff winter rain water. Along the path to the fortress is a barrel vault constructed above one of the cisterns.

Other pools and cisterns are spread along the stretch of the national park.

Closer to the fortress is an Ottoman period lime kiln. The kiln, measuring 4m in circumference, was used to burn limestone. The process produced quicklime through the calcination of limestone. It required a temperature of 900 degrees which was reached in the oven, thanks to the dome that covered the pit where the fire was baking the limestone. The product, quicklime, was used as a sealant to cover the surfaces of the cisterns, thus preserving the water in the reservoirs. It was also a key ingredient for the process of making cement.

Etymology (behind the name):

Names of the city thru various conquerers:

- Reshef, Arshaf – Phoenician name, based on their deity – Reshef (god of war and storms)

- Apollonia – Hellenistic name, based on Apollo (god of sun and light)

- Suzussa – Byzantine name (a Christian name, meaning: city of the Saviour)

- Arsuf – Arabic name `(based on the Phoenician name)

- Arsour – Crusader name (based on the Arabic name)

- Rishpon – modern Hebrew name of the nearby community (based on the Phoenician name)

Links and References:

* Archaeology:

- Apollonia-Arsuf Excavation Project

- Arsur Castle maritime installation Dan Mirkin, Deborah Cvikel & Oren Tal

- Apollonia national park

- A Bilingual Greek-Samaritan Inscription – Oren Tal, 2015

- Raw Glass and the Production of Glass Vessels at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel – Ian C. Freestone, Ruth E. Jackson-Tal, and Oren Tal (pdf)

* Internal:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

BibleWalks.com – tour the Land with a Bible in the hand

Zakkur <<–previous Sharon site—<<< All Sites>>>—next site–>>> Red Tower

This page was last updated on Apr 14, 2018 (Added Arsuf battle illustration)

Sponsored links: