The impressive Arbel cliff overlooks the Sea of Galilee. Its large sets of caves were used for shelter and as a fortress.

Home > Sites > Sea of Galilee> Arbel area > Arbel Cliff

Contents:

Background

Location

Biblical Map

History

Structure

Photos

* General views

* Trail

* Lower level

* Middle level

* Upper level

Biblical Refs

Historic Refs

Links

Background:

The Arbel Cliffs hang over the sea of Galilee, and its natural caves were used as shelters for rebels against Herod, fortress during the revolt against the Romans and was fortified again in later periods. An Ottoman period fortress was built into some of the caves. Ruins of Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine villages lie below the cliffs and on its south-western side.

This web page focuses on the caves of the northern face of the Arbel. For other sites in the Arbel area, visit the overview page.

Location and Aerial Map:

The cliffs are located on the north-west side of the Sea of Galilee (actually, it is a lake). They are located 4 Kilometers north of Tiberias. They stand over Mary Magdalene’s village, today a town called Migdal. The observatory terrace, where the photos are taken, are at the top of the south-side cliffs, at 181 meters above sea level. The lake is 200 meters under the sea level, so this is a difference of almost 400 meters!

An aerial map is shown below, indicating the major points of interest around the cliffs of Arbel.

Biblical map:

A map of the Biblical period is illustrated in the following figure. Arbel is located above the ancient trade routes between the south-west (via Yokneam or Megiddo) and the north-east (via Capernaum, Bethsaida to Damascus and beyond). Another route passes along the shores of the Sea of Galilee towards Tiberias, then south to Beth She’an (Skythopolis).

(based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

History:

Photos:

(a) General View:

The Arbel Cliffs overlook the Sea of Galilee and show a spectacular panorama. The following photo was taken from the observatory terrace on the top of the cliffs, overlooking the north side of the sea of Galilee. The first two villages are Migdal (center left, where the road bends) and Kibbutz Ginosar (center; on the shore). Just above that, in the background on the beaches of the lake is the ancient village of Capernaum. Further to the east is where the Jordan river flows into the lake, and in its background and along the right side of the lake are the Golan heights.

The Arbel cliff is 180m above sea level, and 380m above the Sea of Galilee.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The following photo shows a view of the Arbel cliff as seen from the sea of Galilee. The cliff is 1,750m long, 100m high, and has a steep, almost vertical, slope to the valley below. There are hundreds of caves in the cliff. Most of the caves were created by nature – rain and wind dissolved the limestone and opened up the cavities. The caves are structured in tiers, with some located higher up on the cliff and others lower down. Some of the caves were enlarged and used for residential, as hiding complexes, or fortified. Some of the caves are connected by narrow passages and hand-carved stairways.

Under the cliff are the ruins of the Roman city of Arbela.

(b) Walk to the cliff

The caves on the Arbel are on its north face. They could be reached from the valley below by a steep ascent. However, we reached the caves from the summit where we parked the cars. There are 2 options to descent from the summit – from the west side or the east side, and we hiked from both sides in the past. This time our group descended from the east side of the summit, as seen here.

The trail descends to the bottom of the cliff. The descent is not so easy, and takes a while to carefully climb down between the rocks.

The trail continues westward along the foothill, just below the cliff. This trail is leveled and easy to walk along it.

In this photo, on the other side of the Arbel valley, is Mt. Nitai. That cliff was in ancient geological periods part of Mt. Arbel, but split. It also has hundreds of caves cut into the surface.

Along the trail are small and large caves, and cows that graze in the foothills.

Continuing along the trail…. what a view!

Along the trail are wild flowers, such as this Israeli Luf (Arum Palaestinum). It is poisonous and has a smell of rotting flesh.

Another poisonous flower – Golden Henbane (Hyoscyamus aureus), Hebrew: שיכרון זהוב. It is poisonous to all livestock and humans, even at with a low dose.

Above the trail is the tall cliff. Many small openings are seen on its surface.

The trail continues along ~800m.

The valley below, Nahal Arbel, is more than 300m lower than the trail. On the right side of the photo are the houses of the Arab village of Hamaam. Mt. Nitai cliff is seen here on the left. On its foothill is a Roman/Byzantine period Jewish village of Horvat Vradim.

(c) The lower cave complex

The lower level of the caves are seen at the bottom of the cliff.

Along the trail are a number of caves, and cattle that herds in the area.

Walls were built over the openings of some of the caves.

The lowest set of caves had some of the largest openings, making them more vulnerable but also easier to supply with food and water. Likely used as entry points, storage rooms, or areas for lower-ranking defenders.

Another cave with a wall built at its entrance:

(d) The middle cave complex

This is the largest section of the fortress-like cave system. It consists of multiple interconnected caves, which were modified over time to serve as living quarters, storage rooms, and defensive strongholds. Stone walls were built across cave entrances to fortify them, some reaching several meters in height.

A view of the middle level:

A staircase, made of hewn basalt stones, leads up to the middle level.

A closer detail of the staircase:

Walls were built along the entrances to the caves.

A closer detail of the wall is next. Thick stone walls were built across the mouths of the caves, creating a fortress-like structure.

The balcony above the wall is seen here.

A view of this section as seen from the level above it. The mouth of this cave is vary large and the wall protected it.

The middle level is the largest section of the fortress-like cave system, consisting of multiple interconnected caves, which were modified over time to serve as living quarters, storage rooms, and defensive strongholds. Evidence of rock-cut staircases and tunnels suggests that these caves were connected internally, allowing defenders to move between them safely.

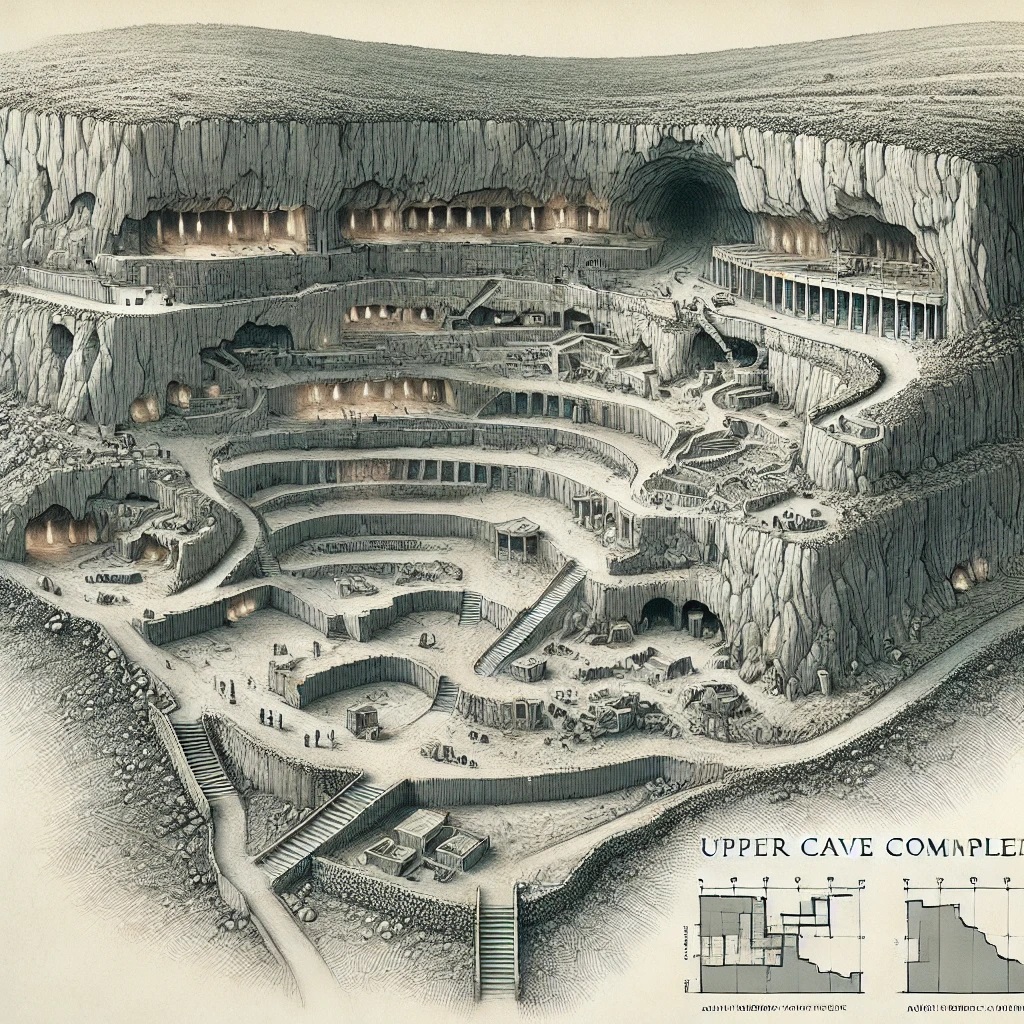

(e) The upper cave complex

Located at the highest points of the cliff, these caves were the most difficult to access. Likely served as watchtowers or high-command posts due to their strategic vantage points over the Sea of Galilee and the surrounding valley.

A staircase leads up to a higher level. Stairs and ladders were carved into the rock, connecting different levels of the fortress.

A view of the staircase and the upper level above it:

Some staircases lead to hidden chambers, possibly used for storage.

The upper terraces likely served as watchtowers or high-command posts due to their strategic vantage points over the Sea of Galilee and the surrounding valley.

A view of the upper level and the middle level:

An interconnecting passage way inside the Ottoman period fortress structure:

Some walls contained narrow firing slits, allowing defenders to shoot arrows while remaining protected.

Other sections of the upper level:

Biblical References:

(a) Hosha (10:14 ,New International Version)

This old testament text talks about a battle, but it is not clear if “Beth Arbel” refers to this site, although the dashing to the ground might imply heights. Note that “Shalman” may imply to Shalmaneser III, the Assyrian king who invaded to Israel in the first Assyrian intrusion (841BC), causing damages to Hazor and other northern cities.

“the roar of battle will rise against your people, so that all your fortresses will be devastated as Shalman devastated Beth Arbel on the day of battle, when mothers were dashed to the ground with their children.”

Basalt stele of Shalmaneser III (858-824BC), city of Assur

[Istanbul Archaeological Museum]

Historical References:

(a) Josephus Flavius (Antiquities of the Jews – Book XII, 11, 1)

Josephus, in his classic writings almost 2000 years ago, describes the military campaign of Bacchides, a Syrian general, against Judea, after the defeat of Nicanor by Judah the Maccabee (167 BCE)-

“…. sent Bacchides again with an army into Judea, who marched out of Antioch, and came into Judea, and pitched his camp at Arbela, a city of Galilee; and having besieged and taken those that were there in caves, (for many of the people fled into such places,) he removed, and made all the haste he could to Jerusalem”.

Roman soldiers march along a road – AI generated by Stable Diffusion

(b) Josephus Flavius (The Wars Of The Jews, Book 1, 16, 4 & 5)

Josephus describes the crash of the revolt by Herod the great (at 39/40BC), and the techniques to lower catch or kill those who hided in the caves :

“…so Herod willingly dismissed Silo to go to Ventidius, but he made an expedition himself against those that lay in the caves. Now these caves were in the precipices of craggy mountains, and could not be come at from any side, since they had only some winding pathways, very narrow, by which they got up to them; but the rock that lay on their front had beneath it valleys of a vast depth, and of an almost perpendicular declivity; insomuch that the king was doubtful for a long time what to do, by reason of a kind of impossibility there was of attacking the place. Yet did he at length make use of a contrivance that was subject to the utmost hazard; for he let down the most hardy of his men in chests, and set them at the mouths of the dens. Now these men slew the robbers and their families, and when they made resistance, they sent in fire upon them [and burnt them]; and as Herod was desirous of saving some of them, he had proclamation made, that they should come and deliver themselves up to him; but not one of them came willingly to him; and of those that were compelled to come, many preferred death to captivity. And here a certain old man, the father of seven children, whose children, together with their mother, desired him to give them leave to go out, upon the assurance and right hand that was offered them, slew them after the following manner: He ordered every one of them to go out, while he stood himself at the cave’s mouth, and slew that son of his perpetually who went out. Herod was near enough to see this sight, and his bowels of compassion were moved at it, and he stretched out his right hand to the old man, and besought him to spare his children; yet did not he relent at all upon what he said, but over and above reproached Herod on the lowness of his descent, and slew his wife as well as his children; and when he had thrown their dead bodies down the precipice, he at last threw himself down after them. By this means Herod subdued these caves, and the robbers that were in them. “

(c) Josephus Flavius (Life,37)

In this text, Josephus, as the northern commander of the revolt against the Romans before he came a writer, fortified (66AD) the Arbel cliffs as a preparation for the Roman reprisal against the revolt:

“I also fortified, in the Lower Galilee, the cities Tarichee, Tiberias, Sepphoris, and the villages, the cave of Arbela,… I also laid up a great quantity of corn in these places, and arms withal, that might be for their security afterward”.

Links:

* External links:

- Har Nitai and Wadi Hamam – Uri Davidovich, Micka Ullman, Uzi Leibner (2013)

- The fortified compound on top of Mt. Nitai – Benjamin Arubas, Uzi Leibner, Uri Davidovich (Kadmoniot 149 (2015), pdf)

* Internal links:

- Hiding complexes

- Arbel sites (overview)

BibleWalks.com – walk with us through the sites of the Holy Land

Arbel<<<—Previous site —<<<All Sites>>>–-next Sea of Galilee site –>>> Magdala

This page was last updated on Mar 12, 2025 (new page)

Sponsored links: