A karst system cave in central Samaria, used as a refuge place over thousands of years.

Home > Sites > Samaria > El-Janab refuge cave (‘Usarin cave)

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Location

* Entrance

* Inner Areas

* Findings

Etymology

Links

Overview:

A karst system cave in central Samaria, used as a refuge place over thousands of years. Archaeological survey dated findings from the Chalcolithic thru the Mamluk periods (5th millennium BC to the early 2nd millennium AD).

Map / Aerial View:

An aerial map is shown here, indicating the major points of interest around the site. The site is 4km east of Tapuach junction, on the north side of Cross-Samaria highway (road #505 Tappuach-Migdalim). The altitude of the site is 702m, rising 150m above the valley, and at a distance of 550m north of the valley.

History:

- Chalcolithic thru Mamluk periods

The el-Janab (‘Usarin) cave was in use in various historic periods, probably used as a hiding place during turbulent periods. The 2017-2018 survey yielded finds of the following periods: Late Chalcolithic, Early Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age I, Iron Age II, Persian, Early Hellenistic, Early Roman, Ayyubid, and Mamluk periods.

- Hiding places

Hiding caves in ancient Israel, often referred to as “refuge caves”, were underground systems used for protection during times of conflict and invasion. These complexes played a crucial role in the survival strategies of the population during periods of unrest. The Bible describes such places (Psalm 27:5):

“For in the day of trouble he will keep me safe in his dwelling; he will hide me in the shelter of his sacred tent and set me high upon a rock.”

More about various historic methods and sites that were used for refuge is detailed in our summary page of hiding complexes in the Holy Land.

Hiding in natural caves (Image created by AI using DALL·E through OpenAI’s ChatGPT)

-

- Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

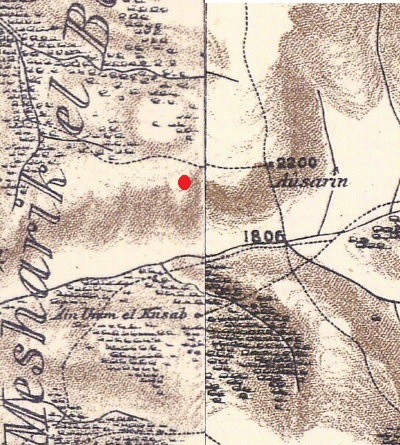

Conder and Kitchener of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) surveyed the area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) in 1874-75. This is a section of their map, focusing on the area, with a red dot that we marked pointing on the location of the cave. The site is west of the Arab village of Ausarin (‘Usarin). South of the cave is the valley of el Janab, marked as a solid line.

Part of map sheets 14-15 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877. (Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Victor Guérin visited the area in 1875 and noted that Ausarin is a village situated on a hill.

- Modern period

The cave was mapped in years 2017-2018. Biblewalks visited the site for a photo session on July 2020.

Photos:

(a) Location

The cave is located at the top of the northern bank of the valley known as Wadi el Janab. The valley is seen here in this south view, facing the village of Kubalan on the other side of the valley. The modern west-east road (#505) is just 100m south of the cave.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The cave is located on a public area, 1.2km west of ‘Usarin (Osarin, Ausarin), an Arab village in central Samaria. ‘Usarin is seen in this east view from the area of the cave.

Based on ceramic dating of pottery sherds, the village of ‘Usarin was settled during the Iron Age II, the Crusader/Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods, so these villagers may have used this cave as a refuge during hard times. At an earlier period (Iron Age I) that village was located on a commanding hill (alt. 713), only 600m east of the site.

Another larger town was Akraba (4km west of the cave) = the regional administrative center during the Roman period. Ceramic dating in Akraba added the Roman/Byzantine period to the settlement periods. Two major revolts occurred during the Early Roman period (Great Revolt and Bar Kochba revolt).

(b) Entrance

The el-Janab cave is located on a rocky slope above the northern bank of wadi el-Janab. Its entrance is hidden amid the greenery seen in this photo.

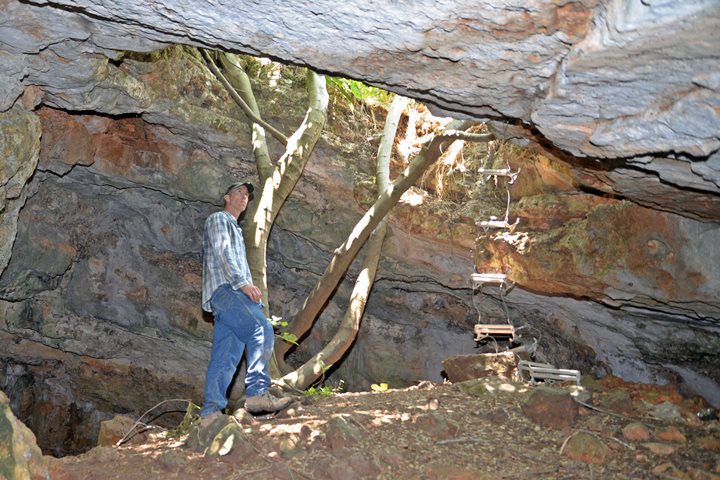

Entrance to the cave is through a 3m wide vertical opening. Descent to the cave is assisted by the branches of a fig tree that grows out of the mouth of the cave. A rope ladder, seen here on the right, also supported the vertical descent to the cave.

The cave consists of irregularly arranged chambers, with passages of various sizes between the chambers. The surveyors mapped the inner side of the cave and named 6 chambers (‘A’ thru ‘F’) in 3 levels (main level, middle level and lower level).

The entrance leads to an area between two chambers – ‘A’ (10m x 15m) and ‘B’ (10m x 25m).

The surface is covered by debris that accumulated over the years, and few findings were find on the top chambers (‘A’-‘B’) near the cave’s entrance. Most of the pottery sherds, stone vessels and coins were found in the deep three internal chambers (‘C’-‘E’) far from the entrance.

From the entrance chambers ‘A’-‘B’ are passages to the inner chambers:

Chamber ‘E’: On the north east side of chamber ‘A’ is a small passage that leads to chamber ‘E’ (5x17m, 3m high). This chamber has terrace walls that were constructed in antiquity.

Chamber ‘D’: A low and narrow passage connects ‘E’ to ‘D’.

Chamber ‘F’: On the east and south sides of chamber ‘B’ are passages to chamber ‘F’.

Chamber ‘C’: On the west side of chamber ‘B’ is a passage to chamber ‘C’.

(b) Inner area

The largest chamber is ‘C’, located on the west side of the cave.

This chamber measures 17m x 20m, and is up to 11m high.

A north west view of Chamber ‘C’:

Another southeast view of Chamber ‘C’:

The floor of chamber ‘C’ is level. It is covered with stalagmites, rocks and a thin layer of dark sediment.

Stalagmites (upward growing mound, as seen below) accumulated in the cave. They were made of mineral deposits that have precipitated from water dripping onto the floor and side of walls of the cave. Stalactites (downward growing mounds) also accumulated on the ceiling and side of walls.

On one of the walls is an Arabic text that was added in recent years.

(d) Findings

The 2017-2018 survey yielded finds of the following periods: Late Chalcolithic, Early Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age I, Iron Age II, Persian, early Hellenistic, Early Roman, Ayyubid, and Mamluk periods. The human activity in the cave spans the 5th millennium BC to the early 2nd millennium AD.

The breakdown of 100 pottery and stone vessels was: Storage Jar (38%), Jug and Juglet (23%), Cooking pot or casserole (15%), Bowl (14%, Lamp (4%), and Other (6%). It is surprising to see such a low percentage of oil lamps, as the cave is totally dark in the inner chamber areas.

The survey also unearthed 22 Medieval Islamic coins.

During our follow up visit to the site, we have collected the following undated potsherds.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- Wadi el Janab – the nearby valley on the south side of the cave

- el-Janab – Arabic, for ‘next to’ or ‘Sir’ (an honourary title).

- el Janab cave – named after the Wadi

- ‘Usarin cave – another name of this cave, named after the village

- ‘Usarin – name of the Arab village east of the cave

Links:

* External links and references:

- An Archaeological Survey at el-Janab Cave, Central_Samaria – Dvir Raviv et al., 2022

- Cave Where Generations Hid for 6,000 Years Found in West Bank – Archaeology – Haaretz.com, Feb 2023

- The Numismatic Finds from el Janab Cave. Raviv et al. 2022

* Biblewalks pages:

BibleWalks.com – “Arise, walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it…”

Qa’un <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next site—>>> Horvat Hemed

This page was last updated on Oct 18, 2024 (new page)

Sponsored Links: