Tel Iztabba was the northern extension of ancient city of Beit Shean during the Byzantine period, and the main area of the Hellenistic city, Scythopolis.

Home > Sites > Yizreel Valley > Beit She’an > Tel Iztabba (Tell el Mastabah)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial Views

* West Summit

* City Wall

* Church Martyr

* Church St.Basil

* East Side

* South side

* Kyrie Maria

* Samaritan Synagogue

Biblical References

Etymology

Links

Background:

Tel Iztabba was the northern extension of Tel Beit Shean, and the main area of the Hellenistic city, Scythopolis. On the site are also remains of the Intermediate Bronze period and Byzantine period churches and a section of the Byzantine wall.

Location:

Tel Iztabba is located on the north side of the ancient city Beit Shean (Beth She’an), above the north bank of Harod river which flows to the Jordan river. An aerial map of the ruins of Tel Iztabba are illustrated here.

Tell Iztabba consists of three hills, slanting steeply on the slopes descending toward Harod river. The two western hills of Tel Iztabba are dominated by Byzantine remains, the eastern hill is entirely of the Hellenistic period.

History:

-

Early Bronze period

The Bronze period Beit Shean was established in the Early Bronze age II (early 3rd Millennium). It extended to the hill east of Tel Beit Shean on the south side of Harod valley, and became a large influential city. It is located on a prime location – in the center of major ancient crossroads (North-South connected Asia Minor to Egypt, and West-East connected the sea to Jordan and Arabia).

- Intermediate Bronze period

At the end of the Early Bronze Age III, most of the residents on Tel Bet She’an moved the level ground north of the Harod valley, while few remained on Tel Beit Shean itself during the Intermediate Bronze Age (25th-20th century BC). The town was constructed on a low level above the bank, on the west side of Tel Iztabba, covering an area of several dozen dunams. The houses were built of mud and various materials, and the residential areas were divided with streets. At the end of this period the town was deserted.

A large necropolis of this period was also found on Tel Iztabba with hundreds of tombs.

After destroyed by fire, the Bronze period city of Beit Shean declined into a small Middle Bronze age town (19th-15th century BC) and settlement on Tel Iztabba was abandoned.

- Hellenistic period – Nisan-Scythopolis

The site regained importance during the Hellenistic period, following Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BC, a time when Greek culture and language spread across the Near East.

During the 3rd century BC the city was rebuilt on the top of the Tel Beit Shean on the south bank, and to the north of it across Tel Iztabba. The city was renamed Scythopolis and Scython-Polis, named after the veterans who resettled the Hellenistic city in 633 BC. The Scythians were a group of nomadic peoples from the region north of the Black Sea, who, in some periods, migrated or were employed as mercenaries in different parts of the ancient world. The name “Scythopolis” means “City of the Scythians,” indicating their presence or control over the city for a time.

According to Greek mythology the city was founded by the wine God Dionysos who lived in the city. According to the legend, his nursemaid Nysa who breast-fed him was buried in the city, so it was named Nysa-Scythopolis or Nisa.

According to the archaeological excavations, settlement during the Hellenistic period started during the 3rd century BC on top of the elongated ridge on the south east side of Tel Iztabba. This area was later protected by the Byzantine period northern city wall. Only at a later phase, the settlement expanded to the lower unprotected area closer to the river.

The archaeologists unearthed structures, tools and small objects. Among the findings were hundreds of stamped imported Rhodian wine amphoras.

- Hasmonean Kingdom

The city was an important Greek Polis in the 2nd century BC, but destroyed by the Hasmonaens in about 100 BC. According to the Historian Josephus Flavius (Wars 1 2 3-7):

“John, who was also called Hyrcanus … marched with an army as far as Scythopolis, and made an incursion upon it, and laid waste all the country that lay within Mount Carmel”.

This description shows that the city was a key to the Galilee region, and after its conquest the whole area was under the control of the Jewish Kings.

-

Roman period – a major city

During the Roman period, starting in the 1st century BC, the city became an administration center, and was part of the Decapolis – the league of the 10 cities which were located in a region east of the Jordan river and and north of the city. The league included the cities of Gerasa (Jerash), Gadara (Umm Qais), Pella, Philadelphia (Amman), Capitolias, Raphana, Canatha, Hippos (Sussita), Damascus, and Scythopolis (the largest city).

A well planned city was established to the south and east of the ancient Tel Beit Shean. The new urban design included wide colonnaded paved streets that crossed the civic center at the foothills of the ancient Tel. Large public structures, shopping areas and residential areas were constructed, and the city became one of the most important cities in the region.

- Byzantine period – prosperous Christian city

During the 4th-7th century the city continued to prosper, but the pagan structures were converted to other uses since the majority of the population was Christian.

The size of the city grew to 400 Acres, expanding to all directions, including Tel Iztabba north of Nahal Harod river. Its population grew to 40,000 residents, and a 4.5KM long wall was added around the city at the beginning of the 5th century. In 409, the city was the metropolis (provincial capital) of “Palaestina Secunda”, a region that included the Galilee and northern Trans-Jordan.

The 4th century was a time of transition for the Roman Empire. Constantine the Great had earlier legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, and it soon became the dominant religion in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. However, periods of persecution persisted, especially under Julian the Apostate, who attempted to reverse the Christianization of the empire. Saints like Basil, who suffered martyrdom during these persecutions, were revered as heroic defenders of the faith, and a church was erected on Tel Iztabba in his memory.

The Decapolis city of Scythopolis was known for its Christian communities, churches, and martyrdom sites. On Tel Iztabba there was the Church of Martyr and the Keri Maria monastery.

-

Arab period – Decline and oblivion

The city was conquered in 635 AD and renamed Beisan, a name that preserved the ancient name. The city started a decline during this period, although the new rulers were tolerant: the Umayyads of Arabia (661-750) allowed the citizens to continue practice Christianity. However, this ended in a major earthquake which leveled the city in 749 AD. The city remained in ruins until modern times.

- Ottoman period

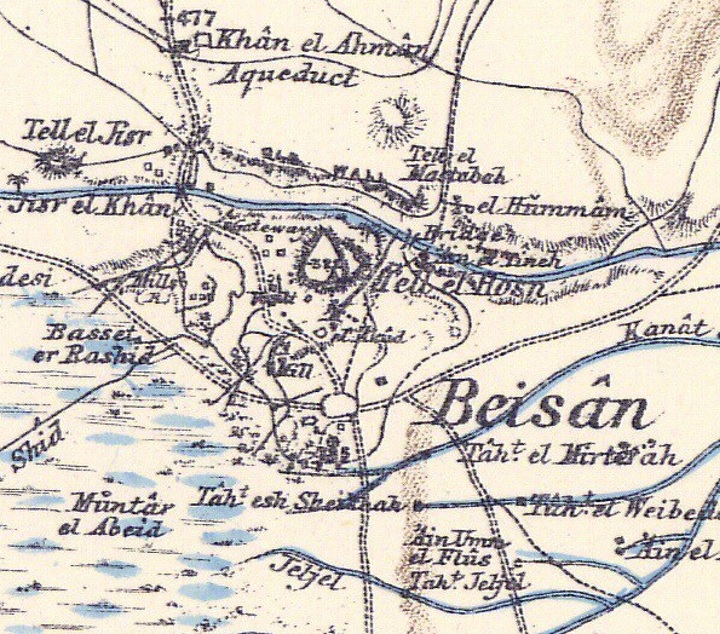

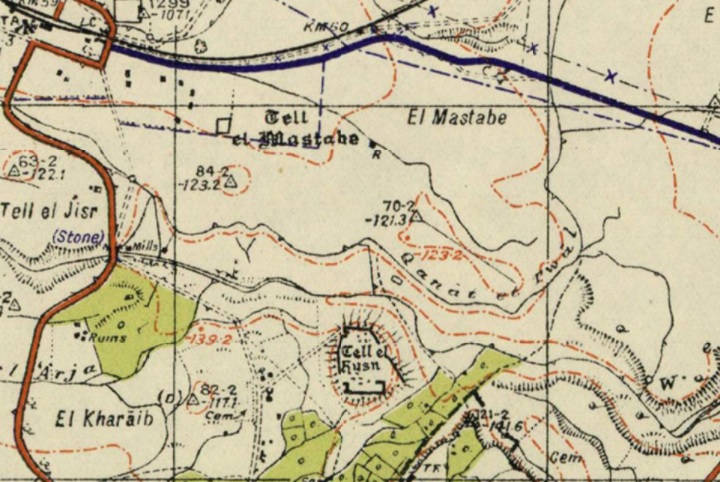

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP), commissioned by the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) in 1873. A section of their map is seen here. The eastern hill of Tel Iztabba is named “Tell el Mastabah” (Arabic: The mound of the bench, same as Hebrew name).

P/O Sheet 9 of SWP, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

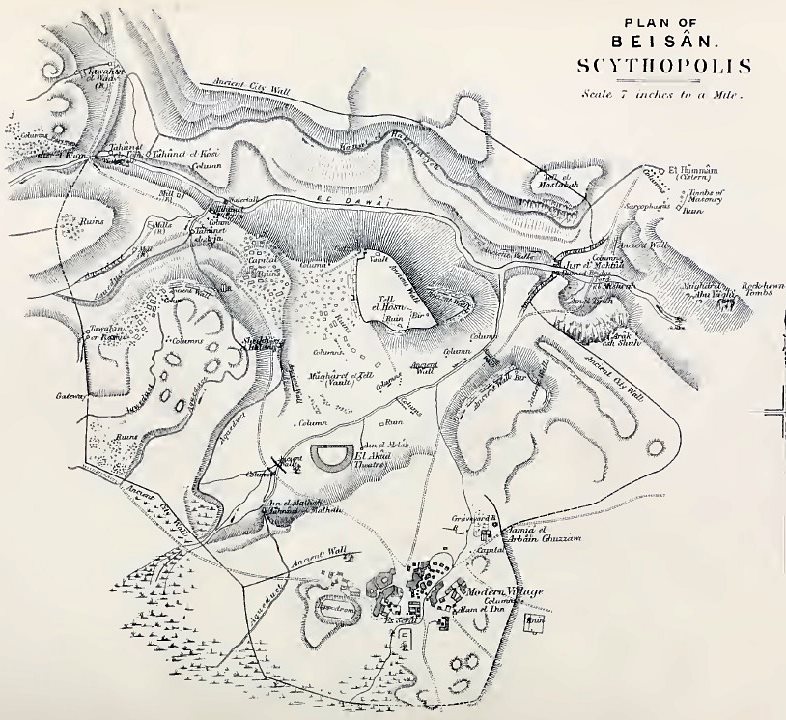

The surveyors also mapped the city and provided the following illustration. Tel Iztabba appears on the top side, stretching above the north bank of Harod river. The city wall encompasses the entire city, as seen in the map, and crosses the height of the ridge of Tel Iztabba.

Illustration on p. 104, Volume 2 Sheet 9 of SWP, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

The authors wrote about Tel Iztabba (Volume 2 Sheet 9 p.105):

“The northern section beyond the stream, but within the walls, includes the church, the tombs, the fort called Tell el Mastabah, and the Hummam. The bridges on the north-east and north-west, and the cemetery to the south of the town, must finally be noticed”.

According to the survey, the eastern hill (named Tell el Mastabah) was used as a fort to protect the northern bridge (p. 116):

“On Tell el Mastabah stands apparently the ruin of a fort, at the north-east corner of the town, guarding the approach by the causeway across the Jisr el Maktila. This roadway leads down by the hollow from El Hummam, and is banked up in parts to the level of the bridge. Tell el Mastabah flanks it, and the ruins of the wall pass across it”.

- British Mandate

A 1940s British map shows the area around the site with more details. The site, located north of the Harod river, is named here by the Arabic name – Tell el Mastabe (mound of the bench – same meaning as Iztabba). No ruins are seen on Tel Iztabba. South of the Harod river is Tell el Husn – the Biblical mound of Beit Shean.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

As illustrated on all above maps, an aqueduct (Qanat et tuwal) crosses the southern foothill, bringing water from the Harod river, from a higher point near the western bridge, to the Roman town of Dabayib et Tuwal and to the farming fields.

-

Modern Times

The site was first excavated in 1921–1933 by an expedition from University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, which exposed a necropolis comprising hundreds of tombs from the Intermediate Bronze Age. The excavations indicated that the remains of the site and the necropolis cover an area of more than 200 dunams. A ceramics survey (1962) dated the pottery from Intermediate Bronze Age, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods. Renewed excavations are on going as seen in the aerial view.

The new city of Beth-Shean was established in 1949 in the deserted Arab village of Beisan.

In 1949-1957 Noah Merdinger, the first mayor of Beth-Shean, founded the Beth Shean Museum and conducted the digs around the Tel. The Roman theater was excavated in the 1950s (Appelbaom), and major excavations continued in 1983 (Yadin/Geva) and 1989-1996 (A. Mazar). The Tel of Beit Shean and the civic center were excavated by Mazor and Bar-Natan, Tsafrir and Foerster. Over 20 layers were excavated in the Tel, attesting to the successive construction of cities one on top of the ruins of the other, spanning more than 2,000 years.

Photos:

(a) Aerial Views

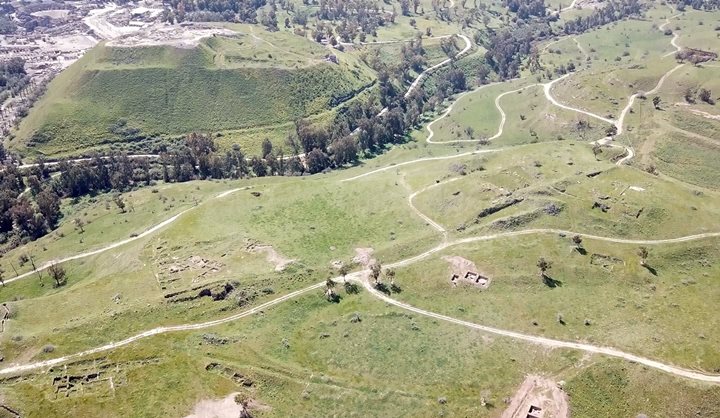

This drone view captured Tel Iztabba from the north west side. The Bronze/Iron age Tel Beit Shean is seen behind the valley of the Harod river. Behind it are the ruins of the Roman/Byzantine city, which was accessed from a great bridge seen here inside the Harod valley on the left side.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

A closer view of the excavation areas is below. There were active excavations on the north eastern side during our visit on March 2023, seen here in the 3 bright squares of excavations.

A drone captured these sights of Tel Iztabba. The drone starts from the north side, passes through the excavated city wall and churches, then views the area of the Jordan valley on the east side.

(b) South West

The highest point on Tel Iztabba is on the south western side of the mountain. Here are several churches and the city wall that crossed the hill from west to east.

Next – a view from the summit of the ridge, towards the east side. The Hellenistic period city started along the elongated ridge on the south east side of Tel Iztabba.

(c) Byzantine City Wall:

The city of Beit Shean expanded during the Byzantine period. The size of the city grew, expanding to all directions, and its population grew to 40,000 residents.

To protect the city a 4.5KM long wall was constructed in the early 5th century encircling the city. The width of the wall was 2.5m and the wall was built of masonry blocks that were reused from older structures.

The northern section of the peripheral wall passed here, stretching from west to east along the top of the ridge. This is the base of the wall.

Another section of the wall is seen here, separating the old and new martyr churches.

(d) Church of the Martyr (south of the wall)

On a high area of the western hill, on both sides of the city wall, are two churches.

The newer church is named after an unnamed martyr mentioned in a Greek mosaic inscription. It was erected on the inside of the Byzantine city walled area, and is adjacent to it. This church and the monastery complex was built after the old martyr church, located on the external side of the wall, was destroyed following the Samaritan revolt of 529 AD, and was rebuilt inside the city walled area.

This aerial view shows the location of the ruins of the church, on the top of the western hill. Notice the line of the wall on the left side of the church.

According to Di Segni (2022), the monastery was dedicated to the local martyr, St. Basilius.

Who was St. Basil? Di Segni suggested that St. Basil was executed with seventy companions in the Diocletianic persecutions. These persecutions (303-313 AD) were the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Yet another theory was that Saint Basil was martyred for his Christian faith during the persecutions under Emperor Julian the Apostate (reigned 361–363 AD). Julian sought to restore Roman paganism and, in doing so, persecuted many Christians who refused to renounce their faith. Basil’s refusal to offer sacrifices to pagan gods or participate in Roman religious rituals likely led to his arrest and eventual martyrdom. His death made him a symbol of steadfast Christian faith in the face of persecution.

Another tentative identification for the martyr commemorated by this church is Procupius, who was beheaded in 303 AD.

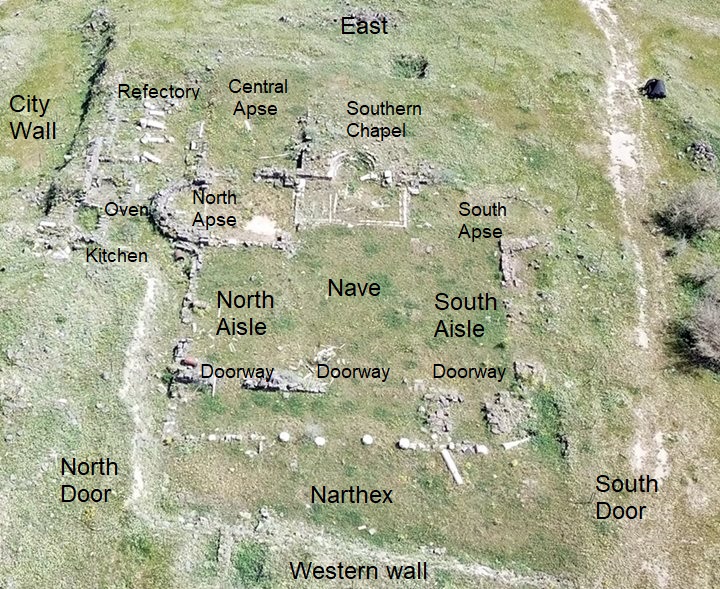

A closer view of the ruins is from a drone with a view towards the east. The church was built as a basilica. It had one central apse and one secondary apse oriented towards the east, and two side apses towards north and south.

The illustration below details the plan of the monastery. On the west side is the narthex (23m x 11m), with 8 columns standing on a stylobate across the narthex. Entrance to the narthex is from 2 doorways on the north and south sides.

Three doorways access to the Nave (15m x 9m), flanked by aisles (20m x 5.5m) on both sides. Two rows of arches separate the aisles and the nave. On the east side of the nave are two apses on both ends, a central hall and apse, and a southern chapel.

The hall of the central chapel (15m x 7.8m) ends with an apse (5.5m diameter). Along its south wall was a staircase to the 2nd floor. On its north wall is a doorway to the refectory, adjacent to the city wall. On its west side is a kitchen, with an oven. The floors were covered with beautiful mosaics.

Central apse:

A view of the main apse, on the east end of the church:

A closer view of the central apse is below. Its diameter is 5.5m. At its center stood an altar. Below the floor of the bema were remains of a reliquary.

A square marble screen colonnette, with grooves that ran along the sides. This may have been a part of the chancel screen that separated the bema from the rest of the hall.

A section of the mosaic floor:

Southern chapel:

An adjoining second chapel is located on the south side of the main apse. Its apse is also oriented towards the east:

A closer view of the apse of the southern chapel:

Refectory:

The refectory, on the northern section in the church, is adjacent to the Byzantine wall. It is seen below.

Notice the marble columns that collapsed after the 749 AD massive earthquake that devastated the city.

Findings:

A carved marble stone. It seemed, at first impression, as a a sun dial.

Fragment of roof tiles indicate that the church had a tiled roof.

(e) Church of Saint Basil the Martyr (north of the wall)

The church commemorated Saint Basil of Scythopolis, a local martyr from the 4th century AD, during the Byzantine period, whose life and martyrdom would have been of particular significance to the Christian community in Beit She’an (Scythopolis).

This aerial view, looking south, shows the location of the ruins of the church, on the top of the western hill. The line of the Byzantine city wall is seen behind it, as this church was outside of the city walls.

This church was destroyed following the Samaritan revolt of 529 AD, and was rebuilt as the “new” martyr church inside the city walled area.

A closer view:

Saint Basil was reportedly martyred for his Christian faith during the persecutions under Emperor Julian the Apostate (reigned 361–363 AD). Julian sought to restore Roman paganism and, in doing so, persecuted many Christians who refused to renounce their faith. Basil’s refusal to offer sacrifices to pagan gods or participate in Roman religious rituals likely led to his arrest and eventual martyrdom. His death made him a symbol of steadfast Christian faith in the face of persecution.

A eastern view of the apse:

A section of the mosaic floor:

(f) Eastern side

New excavations are held on the northern foothills of the east side of Tel Iztabba. They probably are dated to the Intermediate Bronze period.

During our visit we noticed a ceramic fragment of a vessel, dated Bronze period.

(g) Southern side

The southern foothills of Tel Iztabba reach the valley of the Harod river. This view is towards the Roman bridge that connected the hill to the main city of Beit Shean.

Next – a view of the valley of Harod, at the southern foothills of Tel Iztabba.

Several columns and other antiquities are found scattered around the valley.

(h) Kyrie Maria Monastery

The Kyrie Maria Monastery in Beit Shean dates back to the Byzantine period (4th–7th centuries AD). It was built in 567 AD on a high level on the north western side of Tel Iztabba, adjacent to the Byzantine city wall.

Located on the western side of Tel Iztabba, this Christian monastery is one of the many religious institutions that thrived in the region during the Byzantine era, when Christianity was the dominant religion in the Eastern Roman Empire. The name Kyrie Maria translates to “Lord, Maria” in Greek, possibly referring to the Virgin Mary or a local saint or to the donator.

The Kyrie Maria Monastery was a typical monastic complex, consisting of living quarters for monks, a church, and areas for prayer and communal activities. One of the most striking features of the monastery is its beautifully preserved mosaic floors. Byzantine art often included intricate mosaics, many of which featured religious symbols such as crosses, animals, and geometric patterns. Some of the mosaics at Kyrie Maria include inscriptions in Greek, revealing details about the monastery’s founders or benefactors.

The main mosaic floor includes a circle inside a fortune wheel bearing shapes of sun and moon inside an even bigger circle divided into 12 sections. Each section depicted a month of a year and its characteristic labor. The fortune wheel is surrounded by paintings of animals and birds.

The church within the monastery likely included a nave and side aisles, with a central space for worship. Like other Byzantine churches, it would have been adorned with religious iconography and possibly marble decorations.

Like many Byzantine-era Christian sites, the Kyrie Maria Monastery fell into decline following the Muslim conquest of the region in the 7th century CE. As Islam became the dominant religion in the area, many Christian institutions were abandoned or repurposed. After its excavation the area was enclosed in a walled and roofed area and closed to the public. Unfortunately it has since deteriorated and neglected.

(i) Samaritan Synagogue

Ruins of an ancient synagogue are located 200m north east of Kyrie Maria monastery, at a location outside of the Byzantine city wall. This was a Samaritan synagogue from the fourth–seventh centuries AD.

The Samaritans are an ethnoreligious group that traces its origins to the ancient Israelites, with beliefs closely related to Judaism but distinct in terms of religious practices and sacred texts. By the Byzantine period, the Samaritan community was still present in various parts of Palestine, including the Beit Shean area.

The plan of the synagogue is basilica – an elongated rectangular building divided by colonnades. Its apses is oriented towards the south west – in direction to Mount Gerizim. The Samaritans viewed Mount Gerizim as their holiest site, in contrast to the Jewish focus on Jerusalem and the Temple Mount.

The central space of the synagogue was likely an open hall where the Samaritan community gathered for prayer and readings from the Torah. The hall would have been large enough to accommodate the local population but not overly elaborate. At one end of the hall, there would have been a Torah shrine or niche where the sacred scrolls of the Samaritan Torah were kept.

Unlike many Jewish synagogues, Samaritan synagogues did not always have a central bimah for Torah reading. Instead, the reading could have been done from a simpler stand or directly from the front of the hall.

One of the key features of the synagogue was its beautifully crafted mosaic floor, which included geometric patterns, floral designs, and Samaritan religious symbols. Inscriptions found within the mosaic included dedications from donors (written in Greek with Samaritan letters) and the names of the mosaic artists (written in Greek). The artists of the mosaic floor were Marianus and his son Hanina, the same artists of Beit Alpha mosaic floor.

The mosaic floor also featured depictions of the Ark of the Covenant, candelabras, shofars (ram’s horns), and censers on either side. These elements, particularly the depiction of the Ark of the Covenant, are significant in both Jewish and Samaritan religious iconography, highlighting the importance of the Torah and the Temple (or, in the Samaritan case, Mount Gerizim) in their worship practices.

During the Byzantine period (4th century AD), Beit Shean (Scythopolis) became a significant center for the Samaritans. Under the leadership of Baba Rabbah, a key Samaritan reformer and national leader, the Samaritans experienced a resurgence in both religious and political autonomy. Baba Rabbah led a movement of religious reform and social revival, strengthening the Samaritan community and seeking greater autonomy from Byzantine rule. His leadership is associated with a period of prosperity and the construction of synagogues and other religious institutions.

The Samaritans were granted a degree of national sovereignty during this time, but their independence gradually diminished, especially toward the end of the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527–565 AD). Justinian enacted policies that curtailed Samaritan and Jewish rights, leading to tensions and uprisings.

Below: Hundreds of pieces of roof tiles were found during the excavation and collected on a pile.

We found a small remarkable ceramic piece with geometric patterns and a floral design.

Etymology (behind the name):

- Tell el Mastabah Arabic name of the site, means: The mound of the bench.

- Tel Iztabba – Hebrew name, based on the Arabic name, means: The mound of the bench.

- Beit Shean (Beth Shean): Hebrew: Beit (Beth) is “House”; She’an may have been a name of an ancient God. Thus, the meaning of the name is “the house of Shean”.

- Scythopolis and Scython-Polis – the Hellenistic city was named after the veterans who resettled the Hellenistic city in 633 BC. Polis – Greek for city.

- Tel – mound (See more on the story of a Tel).

Links:

* Tel Iztabba:

- Bet Sheʽan, Tel Iztabba HAESI Vol 126 Year 2014 Eli Yannai 02/12/2014 Preliminary report

- Bet Sheʽan, Tel Iztabba HAESI Vol 128 Year 2016 Z. Horowitz and W. Atrash 05/04/2016 Final Report

- Bet Sheʽan, Tel Iztabba HAESI Vol 128 Year 2016 Walid Atrash 20/11/2016 Final Report

- Conservation project – Kyrie Maria Monastery

- Byzantine city wall – Map. (Source Mazor and Najjar, Nyssa – Scythopolis; drawing B. Arubas)

-

The Church of the Martyr and Other Churches at Scythopolis (Beth Sheʼan) = Leah Di Signi, 2022

- Scythopolis – Church of the Martyr – Northeast Insulae project, 2.24

* More of Beit Shean in other BibleWalks pages:

- Tel Iztabba – Flight over the south mound (YouTube)

* Biblewalks info:

-

Roman Streets – in Biblewalks.com

-

Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

* External:

-

Beit She-an including map

BibleWalks.com – walk with us through the sites of the Holy Land

Tel Beit She’an <<<—previous site—<<< All Sites>>>—next site—>>> Balfouriya, Tel Yifar

This page was last updated on Oct 9, 2024 (update)

Sponsored links: