Large Biblical Tel, situated near ancient strategic roads in the Northern Samaria region. Known as the place Joseph was sold to slavery, and as a city attacked by Aram-Damascus.

Home > Sites > Samaria > Tel Dothan

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Wells

* Ascent

* Summit

* Altar

* Valley views

* Pottery

* Summary

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Tel Dothan (also Dotan, Tel al-Hafireh) is a large Biblical mound located in the northern part of Israel, near the modern-day city of Jenin. The site is believed to have been inhabited continuously from the Early Bronze Age to the Hellenistic period.

The site is known primarily for its association with the biblical story of Joseph, who was sold into slavery by his brothers and taken to Egypt. Genesis 37: 17:”And Joseph went after his brethren, and found them in Dothan”. According to the Bible, the brothers threw Joseph into a pit at Dothan before selling him to the Ishmaelites who took him to Egypt.

Excavations at Tel Dothan have revealed the remains of a large fortified city, with a massive wall surrounding the settlement. The site also contains a number of important structures, including a large granary and a temple, which have been dated to the Middle Bronze Age.

In addition to its biblical significance, Tel Dothan is also an important archaeological site because it provides insights into the ancient history of the region. The site has been excavated by several archaeological teams over the years, and their findings have helped to shed light on the political, economic, and cultural life of the people who lived there.

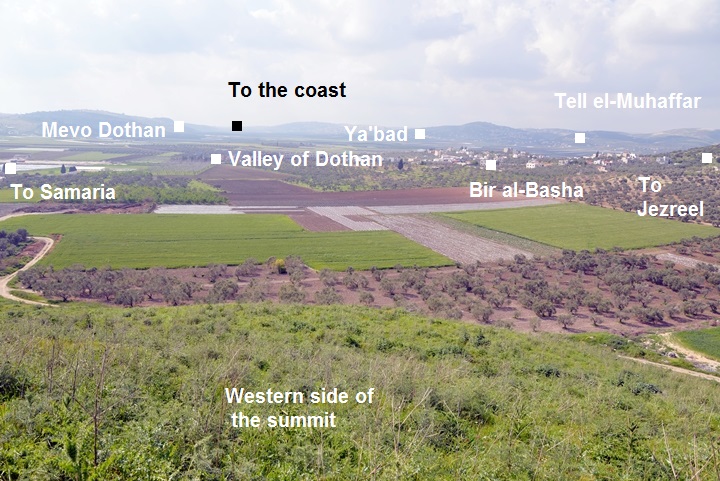

Map / Aerial View:

An aerial map is shown here, indicating major points of interest, and the excavation areas (‘A’ thru ‘T’) that were opened to study the site (Joseph Free excavations, 1954-1964). Tel Dothan (Tel al-Hafireh) rises 60m above the valley of Dothan, and covers an area of 100 dunam (10 Hectares), with and area of 40 dunam on its peak.

The site is located near the main road connecting Dothan valley to the west, and near a road south to the heart of Samaria mountains. Modern highways #585 and #60 follow the same ancient routes.

History:

- Early Canaanite period

The excavations revealed early settlement during the end of the Chalcolithic period . It grew to a heavily fortified walled Canaanite city during the Early Bronze I-III period (3700-2300 BC).

Seven archaeological layers were identified of this period, followed by two layers that were dated to the Middle Bronze period IIb (1750-1550 BC). Few findings were identified to the Late Canaanite and the Israelite I period.

- Biblical events (Bronze period)

One of the Biblical events involved traveling along this route from Dothan to the coast and down to Egypt. Joseph, favorite son of Jacob, and his envy brothers were stationed at that time in nearby Dothan (Genesis 37: 17):

“And Joseph went after his brethren, and found them in Dothan”.

The brothers, envy of Joseph, threw him into a pit, then selling him (Genesis 37:28):

“Then there passed by Midianites merchantmen; and they drew and lifted up Joseph out of the pit, and sold Joseph to the Ishmeelites for twenty pieces of silver: and they brought Joseph into Egypt”.

The eastern route towards the coast was then used by the Ishmeelites merchantmen who came from Gilead, taking him to slavery in Egypt.

A tradition identifies a deep well on the side of the mound as Joseph’s pit. Yet another tradition has the pit located near Ami’ad (Jubb Yussef).

Note that the name Dothan may have been based on a Hebrew word ‘Duth’ – meaning pit.

Joseph sold to the merchantmen – illustration by Dore

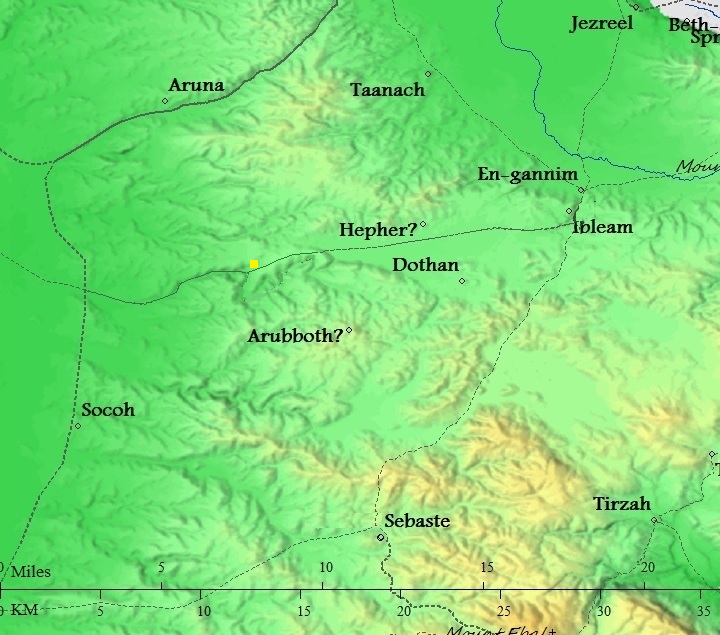

- Ancient roads

The cities and roads during the ancient periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below.

- East-west road: Dothan is marked south of the main road (the “King’s road” – Tarik es-Sultan) from Jezreel valley, via the valley of Dothan, towards the coast. A line of Iron Age sites were identified along this route, including Ferasin (also published in BibleWalks, and marked by a yellow square) and Hepher (Tell el-Muhaffar- an alternative identification to Tel Hefer in the Sharon area). This route is marked ‘B4’ in Dorsey’s “Roads and highways of ancient Israel”.

The route, passing thru the valley of Dothan, was useful during the antiquity. It was a more convenient and shorter route than the two Carmel passes on the north – ‘Ara and Yokneam. The Dothan valley route was the southern path that was suggested by the military advisors to Thutmose III on his inquest of 1492 BC just before the battle of Megiddo. However, he rather took the risky middle route thru the narrow valley of ‘Ara (Aruna, Iron) to Megiddo.

- North-South road: Another road, which is not marked here, passes on the west side of Dothan southwards to Samaria city – the capitol of the Northern Kingdom (here: Sebaste). It is marked by Dorsey as the National highway N1 – from Jezreel, through En-Ganim (Jenin) to Shechem and Jerusalem. It is now highway #60 – the main north-south crossing throughway that cuts thru Samaria and Judea. Dothan served as a gateway on the southern edge of the valley. Yet another eastern route (N24) bypassed Dothan through Kabatieh and via the valley of Marj’ Sanur.

Map of the area around Dothan from Canaanite/ Israelite to Roman period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

- Israelite Kingdom (Iron Age II)

The peak settlement was in the Israelite II period (from 1000 BC), with 4 identified layers. The oldest layer, with a large administration building dated to the 9th-10th century BC, was destroyed by fire – perhaps by the armies of Aram Damascus.

The Israelite city is described by the Bible as a major city, when the King of Aram came to catch prophet Elisha (2 Kings 6:13-14):

“And he said, Go and spy where he is, that I may send and fetch him. And it was told him, saying, Behold, he is in Dothan. Therefore sent he thither horses, and chariots, and a great host: and they came by night, and compassed the city about”.

The archeologists unearthed a fortified settlement of this period in areas ‘A’ and ‘L’ on the south and west sides of the mound. In area ‘L’, on the west side of the summit, they identified a section of the casemate city wall. This design, typical of Iron Age defenses, includes 1m wide inner and outer walls, with 2.5m width between the walls. In this area they mapped 14 various buildings, including several ‘four-room’ houses – a typical design found in Iron Age II residential structures in Israel. Other structures included agriculture installations such as a grain silo. A large administration building (house ’14’), that was identified in this area, may have actually been a ritual place, as a 4 horned altar was recently (2013) found in the rubble.

In area ‘A’, on the south side of the summit, the team unearthed a street, with buildings and installations on both sides, leading to a square courtyard. A 4-room house was found on its northern side. Piles of mud bricks were found there, perhaps part of a clay oven. The city casemate wall, which surrounded the fortified city, was not found in this area as it probably has sank down to the foothills.

Dothan is also mentioned in the external book of Judith (2 passages), in the Rehov synagogue inscription (line 28), and in the Onomasticon (Eusebius, 371):

“Dōthaeim (Dothaim).Where Joseph found his brothers grazing (cattle). It remains (is shown up to today) in the region of Sabaste about twelve miles to the north.)”.

- Assyrian conquest

Dothan was destroyed by the Assyrians during the Tiglath Pileser III inquest (732 BC) or by Shalmaneser V or Sargon II at the end of the Northern kingdom (721 BC). The Assyrians rebuilt the city, as identified by a single short-period layer.

- Other periods

Except for a small settlement during the Hellenistic period and a Mameluke structure on the summit, the city was left mostly uninhabited since then.

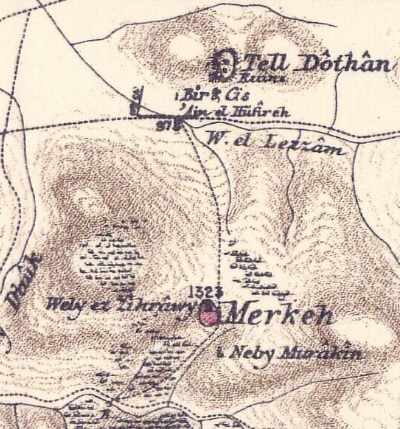

- Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

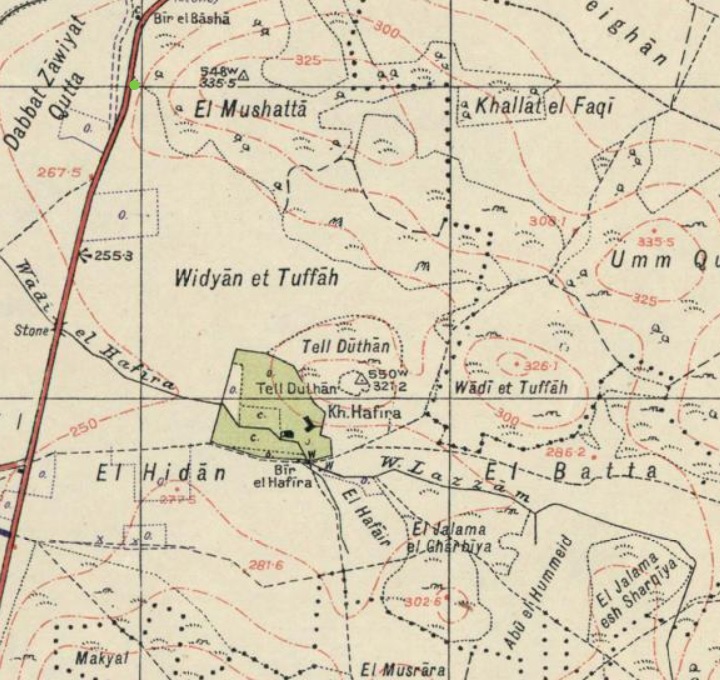

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. This map is part of sheet 11 of their survey results. The ruins are marked only on the south east side of the western hill, probably since they were visible at that time only at this section.

Part of map sheet 11 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Their report of the site was merely (Volume 2, p. 215):

“Tell Dothan—There is a large mound, which appears to be the ancient site of the town. South of it is a well with modern masonry, and a spring (‘Ain el Hafireh) near a cactus hedge, where is a drinking-trough. There is also a modern Moslem building and a few terebinths near the ruins.

‘ Tell Dothan stands close by two wells ; one of them is ancient, and the other modern. The slopes of the Tell and its summit are strewn with materials and numerous fragments of pottery, the sole remains of an ancient city entirely destroyed.’—Guerin, ‘Samaria,’ 219.

This place was discovered by Van de Velde, and identified by him with Dothan of Genesis xxxvii. 17—an identification which seems generally admitted. The name agrees with the old one, and the situation accords, as Guerin carefully points out, not only with the requirements of the narrative in the Book of Genesis, but also with those of 2 Kings vi. 13 et seq., and the two passages in the Book of Judith”.

- British mandate

A map published in the 1940s, with the name “Tell Duthan” and a ruin on its southern foothill named “Kh. Hafira”. The main north-south road passes to the west of the site. During this period a new pump house was built at Bir el Hafira.

https://palopenmaps.org – Palestine 1940s 1:20,000 map

- Modern period

During the period between the Israeli independence and the 6-day-war (1948-1967), the Jordanian army cut communication tunnels and bunkers along the hillsides, damaging the ancient wall around the hill.

The site was excavated in 1954-1962 headed by Joseph P. Free. The team identified 21 different levels. A final report was published by Daniel Master et al. in 2005. The Har Menasseh country survey by Adam Zertal listed the site (volume 1, site 44, pp. 141-142) but referred to the previous excavations.

Tel Dothan is within Area ‘A’ of the Palestinian Authority. Security limitations prevent Israelis to visit the site, which could be organized with the Army.

Photos:

The photos were taken on March 31 2021.

(a) Aerial Views

A view from the south was captured by the drone. Traces of the excavation areas are seen on the summit and along the southern and western foothills. Around the lower sides of the foothills are olive trees, and several modern structures.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

Yet another view from the south east edge of Tel Dothan is next. Notice the vast valley of Dothan in the background, and the houses of the Palestinian village of Bir al-Basha.

![]() The following video shows a view of the site and its surroundings. The drone starts above the south east edge, passes along its southern foothills, then descends to “Joseph pit” where the tour, organized by Midreshet Shomron, was inspecting the well.

The following video shows a view of the site and its surroundings. The drone starts above the south east edge, passes along its southern foothills, then descends to “Joseph pit” where the tour, organized by Midreshet Shomron, was inspecting the well.

(b) Wells

We arrived to Tel Dothan with a group, a tour organized by Midreshet Shomron, guided by Ishay Ben Pazi, and protected by a group of soldiers.

The first station was on the southern side of the mound, where a complex of pools are arranged around a deep well. One of the uses of the pools was for sheep shearing.

The source of the water was from this built well. According to tradition, it is where Joseph was thrown into the pit.

Another structure is located to the west of the well – a pump house that was built during the British mandate period.

The waters are raised by a petrol engine pump and stored in an open pool, then conveyed thru aqueducts to water the fields.

(c) Ascent

The ascent to the summit, 60m in height difference, was along a make shift path. The site is not organized as a public park, nor there are any plans for it. It passed through a number of old houses that are built on the south west foothill, then ascended along one of the excavated areas.

Open excavation trenches, such as this area (‘D’), were cut in several sections on the south west area of the mound. During summer time this will mostly clear up, so it will be easier to see the ruins. But then the great green colors of spring will turn brown.

(d) Summit

The summit of the mound, a large 40 dunam area, was once built and inhabited during the Early Bronze and Iron Age periods. Archaeological excavations opened several areas on the summit and along some of the foothills.

Traces of walls and installations could be seen on the summit. However, most of the excavations areas were covered by weed or covered by soil in order to protect the antiquities.

There are, unfortunately, illicit diggings on the hill. In this recent dig, seen below, many pottery fragments were tossed away as the robbers did not find value in them. This is a sad pattern found in many ancient sites in the territories managed by the the Palestinian authority. It should stop.

(e) Four Horned Altar

One of the interesting elements that are visible, laying in situ between the trenches, is an Iron Age altar stone. It was discovered by chance by two students of Shimon Gibson among the trenches of area ‘L’ in the west side of the summit. The limestone altar, with one intact ‘horn’ and a fragment of another ‘horn’, is dated to the 9th century BC (Iron Age IIb). Its sizes are 65cm x 65cm and the width in its center is 18 cm. It served as the top of the altar, probably standing 65 cm tall, and probably used for offering incense.

The stone was found in the rubble of house ’14’, which was initially identified as an administration building, but the finding of the altar may redefine it as a ritual place. The building was destroyed at the end of the 9th century BC.

- About altars:

There were various types and sizes of altars for different types of sacrifices and in context with various events. One of them is the four-horned altar. The word “altar” means: a structure upon ritual offerings such as sacrifices are made. In Hebrew it is called: Mizbeakh, meaning: place of ritual offering, such as sacrifices. The word appears 111 times in the Old Testament and 22 times in the New testament. Worship sites often contained altars, where sacrifices were made. These shrines were normally located on a high locations, overlooking an open area where the public would assemble and view the ritual service. Therefore, they were referred to as “high places”. The worship sites are called in the Hebrew Bible as “Bamah”, and in plural: Bamot.

Before the first Temple was built in Jerusalem in the 10th century BC, the practice of the worship in the Bamot was common and legitimate throughout Israel. Gradually, they became unacceptable, with Jerusalem becoming the sole place of worship. King Hezekiah of Judah (reign 716-697 BC) enacted religious requiring sole worship in Jerusalem (2 Kings 18:4): “He removed the high places, and brake the images, and cut down the groves”. A hundred years later, the sweeping reforms of Josiah (reign 641-609 BC) also brought major religious reforms, forbidding all sorts of worship outside Jerusalem, and destroying high places from Beersheba to north of Samaria (2 Kings 23:19-20): “And all the houses also of the high places that were in the cities of Samaria, which the kings of Israel had made to provoke the Lord to anger, Josiah took away, and did to them according to all the acts that he had done in Bethel. And he slew all the priests of the high places that were there upon the altars, and burned men’s bones upon them, and returned to Jerusalem..”.

A common type is the four-horned altar. Its style is based on a flat surface with horns on its four raised corners called “horns” (as in bulls). The Bible describes the structure of the altar (Exodus 27:2): “And thou shalt make the horns of it upon the four corners thereof: his horns shall be of the same”. Or another text: (Ezekiel 43:15): “…and from the altar and upward shall be four horns”.

The altar was used for sacrifices, as mentioned in numerous places in the Bible (Leviticus 8:15): “And he slew it; and Moses took the blood, and put it upon the horns of the altar round about with his finger, and purified the altar and poured the blood at the bottom of the altar and sanctified it, to make reconciliation upon it”. However, this small altar may have been only used for offering incense as it is too small for sacrificing animals.

(e) Valley Views

From the western edge of the mound are great views of the vast and fertile valley of Dothan.

In the following western view, looking across the length of the valley towards the coast, the following points of interest are:

- Front: The valley of Dothan, irrigated by Nahal Hadera. This seasonal stream cuts through the mountain area west of the community of Mevo Dothan, then flows to the coast of Hadera.

- Left Background: Samaria mountains,where the mountain pass connected the valley to Samaria city and Shechem

- Right: Arab village Bir al-Basha, situated along highway #60

- Far right background: Tell el-Muhaffar. Another large Biblical Tel (120 dunam); Adam Zertal identified it as the Biblical city of Hefer (rather than its commonly known location on the bank of Nahal Alexander river).

(f) Pottery

A sample of pottery assemblage of Tel Dothan, collected during past surveys, are on display in the Beit Alpha archaeological museum. These vessels are dated to the Iron Age period. From left to right: oil lamp, bowl, two segments of burial goblets.

(g) Summary

This was a short taste of Tel Dothan… We wish to return again to the area and to further investigate the sites along the valley.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- Dothan – Biblical name; perhaps based on the word – Duth – meaning in Hebrew: pit, also: cellar. The PEF dictionary interpreted the name as Dothien – Hebrew for ‘two wells’.

- Tel Dothan – the mound of Dothan.

- Tell Duthan – as appears on the British map (1940s)

- Khirbet Hafirah – Arabic name of a ruin on the foothills of Tel Dothan; Hafira – Arabic and Hebrew for excavation.

Links:

* External links and references:

- “The Manasseh hill country survey” – site 44, volume 3 pp. 141-142 [Adam Zertal – Nivi Mirkam, 2000]

- “The new encyclopedia of archaeological excavations in the Holy Land” [1992 E. Stern editor, Volume 2 pp. 444-446]

- The roads and Highways of ancient Israel – Road B5 on Map 4 (Dothan-Jezreel-Shunem road) and road N1 on map 8 (National highway route).

- A note on Four horned altar of Iron Age from Tel Dothan – Shimon Gibson, Bema’ale Ha’ahr 8th collection, 2018; pp. 151-167; Ariel Univ press.

* Internal Links:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- Shiloh altars – other four horned altars

- Aerial views – Youtube channel by BibleWalks.com

BibleWalks.com – Samaria under your feet

Ferasin <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next site—>>> Burj el Maleh

This page was last updated on Jan 18, 2025 (minor updates)

Sponsored Links: